Welcome to Base Camp, your source for original, in-depth reporting on news and issues impacting the outdoor community.

Subscribe now for free to get access to updates, alerts, and exclusive stories about issues impacting the activities you love.

LAKEWOOD, CO — April 21, 2022

When Katie Gill first read the proposal to add 20,000 Acre Feet of water storage to Bear Creek Lake Park, she thought it was a typo.

“Surely, they put an extra zero, and what they really meant was 2,000 to 2,200.” From there, Gill the Colorado Water Conservation Board — or CWCB — and the Army Corps of Engineers were studying whether it would be possible to use the park for water storage.

According to the CWCB, Colorado’s demand for water will outpace the supply in the next few decades. This is one of the storage locations that’s being looked at to help fill the gap. These are the basics:

This location was picked for study because there’s already a dam built, with an open space to store the water

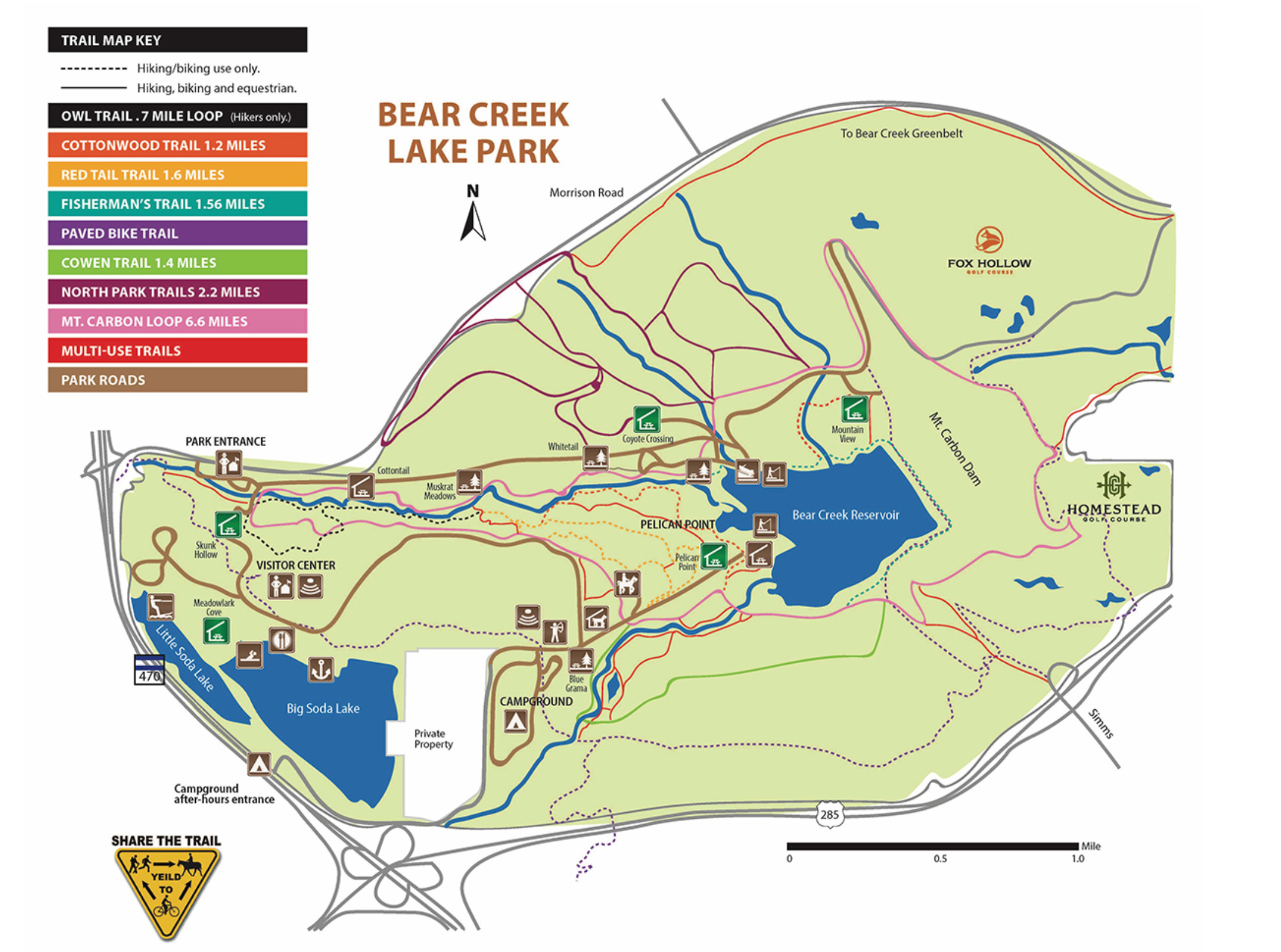

Lakewood operates the area around the lake as a park, on a lease from the Corps. It contains a large network of trails for hiking, biking, and horseback riding

The current flood plan would eliminate more than 600 acres of the park

The Army Corps of Engineers concluded this project will make downstream flooding more likely

This project is still in a study phase, meaning the goal is to determine whether it’s feasible and cost-effective to store water here

Gill realized few other people were aware this process was going on. Even fewer actually believed anything would come of it. Gill created the website, “Save Bear Creek Lake Park,” and is now the chair of the organization working to convince the CWCB to look elsewhere.

This map shows the existing size of Bear Creek Lake, with a light blue overlay showing how big the new flooded zone would be.

I’ve used this map from the Save Bear Creek Lake Park organization, rather than the government-made one, because their markings are transparent — it’s easier to see which trails would be impacted. The map also includes more detailed labeling.

Would the Project Increase Flood Risk in the Area?

Before we even address the impact to park recreation, there’s an obvious point we need to address: the dam’s original purpose.

The city of Denver has a long history of expensive, and deadly floods. The existing dam along Bear Creek was designed to protect the city from these natural disasters.

Before using the site to store more water, the CWCB and the Army Corps wanted to be sure this wouldn’t compromise the flood protection the dam provides. They conducted a study which wrapped up in late 2020, and this is what they found:

The Quick Version

The study is limited, and didn’t fully explore some scenarios that could cause flooding

Increasing the reservoir would increase the risk of downstream flooding, but not the risk of a dam breach

While the Army Corps considers this a tolerable risk, they noted the project may require extra safety features, which would drive up the cost to stakeholders1

The Long Version

If the flood aspect interests you, I dive into these three points in greater depth below. If your primary concern is with the loss of the park itself: by all means, skip down to the “Impact to Recreation” section. (Scroll until you see a little doodle of pine trees.)

I’ve embedded the safety assessment here, if you’d like to read for yourself:

1. This is a Limited Study —

—apparently conducted in a single day (section 1) and without a site visit (section 4.a.)

The team ran the numbers for a “critical duration” of one day (section 4.b.) To you or me, that means they studied what would happen during a big rainstorm. There are other weather conditions that could produce longer flood risks, but these were not studied.

2. The Project Would Increase the Risk of Downstream Flooding

There are more properties, and more people living downstream of the dam, compared to when it was built. That means a breach or flood has potential to do more damage. But the report concludes the chances of a weather event that would cause this problem have gone down. (section 5.a.)

The real risk, according to the report, is increased chances of downstream flooding. If the proposed 22,000-acre-foot reservoir gets built, the risk increases by 3/4 of one order of magnitude. Translated to plain English: that means a significant downstream flood is 7.5 times more likely to happen.

Keep in mind, we’re still dealing with extremely small numbers here. Pulling from the report, directly:

“The non-breach life loss threshold was estimated at 1/180,000 years for existing conditions, 1/105,000 years for the 10,000 ac-ft reallocation pool, and 1/55,000 years for the 20,000 ac-ft reallocation pool.” (section 5.b.)

The report concludes that the project isn’t risk-neutral — then again, what is? — but proposes some extra precautions to bring that risk back down.

3. The Army Corps May not be Comfortable with the Risk

The memo addresses some of that risk in the final section:

“The RMC (Risk Management Center) Director expressed concern about the risk of undertaking a reallocation study that may recommend trading flood risk management benefits for water supply benefits. The Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works has indicated an unwillingness to trade flood risk management benefits for water supply benefits…” (section 6.c.)

My reading of this statement is that while the increased flood risk is tolerable, the RMC would rather not take it if it doesn’t have to. This could mean building other expensive flood protection measures, which may make this site a less attractive option to the stakeholders who have to foot the bill.

The Impact to Recreation

Over the decades, the area around the dam and reservoir has turned into quite the local amenity. Bear Creek Lake Park now boasts a sprawling network of hiking, biking, and horseback riding trails. There are also spots for fishing, camping, boating, and other outdoor activities.

Many of these trails would be underwater if the Army Corps moves forward with the proposal. As Gill puts it:

“This is a place where — without having to drive an hour and a half into the foothills — you can find yourself along bear creek where you hear the flowing river, and the birds and the leaves rustling in the trees. You’re not hearing the sound of traffic. You’re not seeing the traffic. You’re encompassed by this natural experience that’s close to home, that people can enjoy on a regular basis when they need to.”

“Taking that away from this community, in my opinion, would dramatically reduce the quality of life for many, many people. Thousands of people — maybe hundreds of thousands of people.”

“Save Bear Creek Lake Park” has carefully catalogued the specific park features and trails that would be impacted, depending on how large the reservoir is expanded.

You can see that chart here:

Aside from the loss in recreation, organizers warn the expanded reservoir would have environmental drawbacks, specifically the loss of riparian habitats.

These are the areas where rivers and streams interact with the nearby landscape. Aside from providing an important home to countless plants and animals, these areas also help improve water quality by filtering out sediment and pollution.

You can see these habitats in the image above, off to the left side of the lake. Gill estimates that a combined total of 1.75 miles of these habitats would be lost along both Bear and Turkey Creeks.

These are factors the CWCB is considering in the study.

“Bear Creek Lake would by no means would be some kind of silver bullet, and it absolutely is being weighed against a bunch of other potential solutions to meet this water supply and demand gap,” said Erik Skeie, Special Projects Coordinator with the CWCB.

Some of those other proposed solutions mentioned by Save Bear Creek Lake Park:

Dredging the lake to expand storage without flooding more land

Using the secondary embankment to create a second storage pool in the park’s southern grasslands

Using sand and gravel quarries farther downstream for water storage

Skeie explains that at this stage, the goal is to figure out which options are actually possible, and to put a price tag on them.

“That’s what the study is really trying to narrow down: is really, what’s going to be the most feasible alternative, and how much is that going to cost to mitigate recreation impacts, mitigate environmental impacts.”

Are We Building Water Storage for People who Don’t Exist?

Despite what you may think from the traffic, crowding, and high housing prices: Colorado’s population growth has slowed quite a bit during the past few years. This matters because the CWCB’s plan was drafted in 2015, in a period of staggering influx.

That means the numbers they’re using to forecast water need could be out of date. While the state will still need some additional water storage it may not need all of it.

As it stands: this project still has a long way to go before action is taken. The feasibility study alone is a years-long process. But Gill says community members opposed to the project are raising objections now, before the plan builds momentum.

If you haven’t already: please consider downloading the app to ensure new updates never get buried in your inbox. It removes the middleman and helps ensure all the latest stories reach you directly.

If you Enjoyed this Post, Check out This:

How one competitor is trying to save a unique Colorado sport from extinction

The new mountain biking trails coming to Idaho Springs

Or this guide on getting high quality hiking gear, without breaking the bank

Stakeholders, in this case, are the municipalities downstream who would be footing the bill for the project, and also utilizing the extra water storage

Bear Creek Lake Park Could be Flooded to Fill Colorado's Water Needs; Community Members are Pushing Back