Quandary Collapse: Colorado's Most Popular Peak Sees Visitor Numbers Cut in Half

Data from Colorado Fourteener Initiative trail trackers show significant hiker drop-off on popular peaks, but could trouble be brewing elsewhere?

The Colorado Fourteeners Initiative clocked the lowest number of hikers on 14er trails since 2015 — the first full year they’ve been reporting the data. The comeback story is Bierstadt clawing back its number one spot from Quandary by sheer attrition:

Quandary has seen visitors cut in half since Summit County implemented a paid parking. I extensively covered that change in my documentary, “The Alpine Amusement Park.” You can watch below if you’re interested.

NOW PLAYING: "The Alpine Amusement Park"

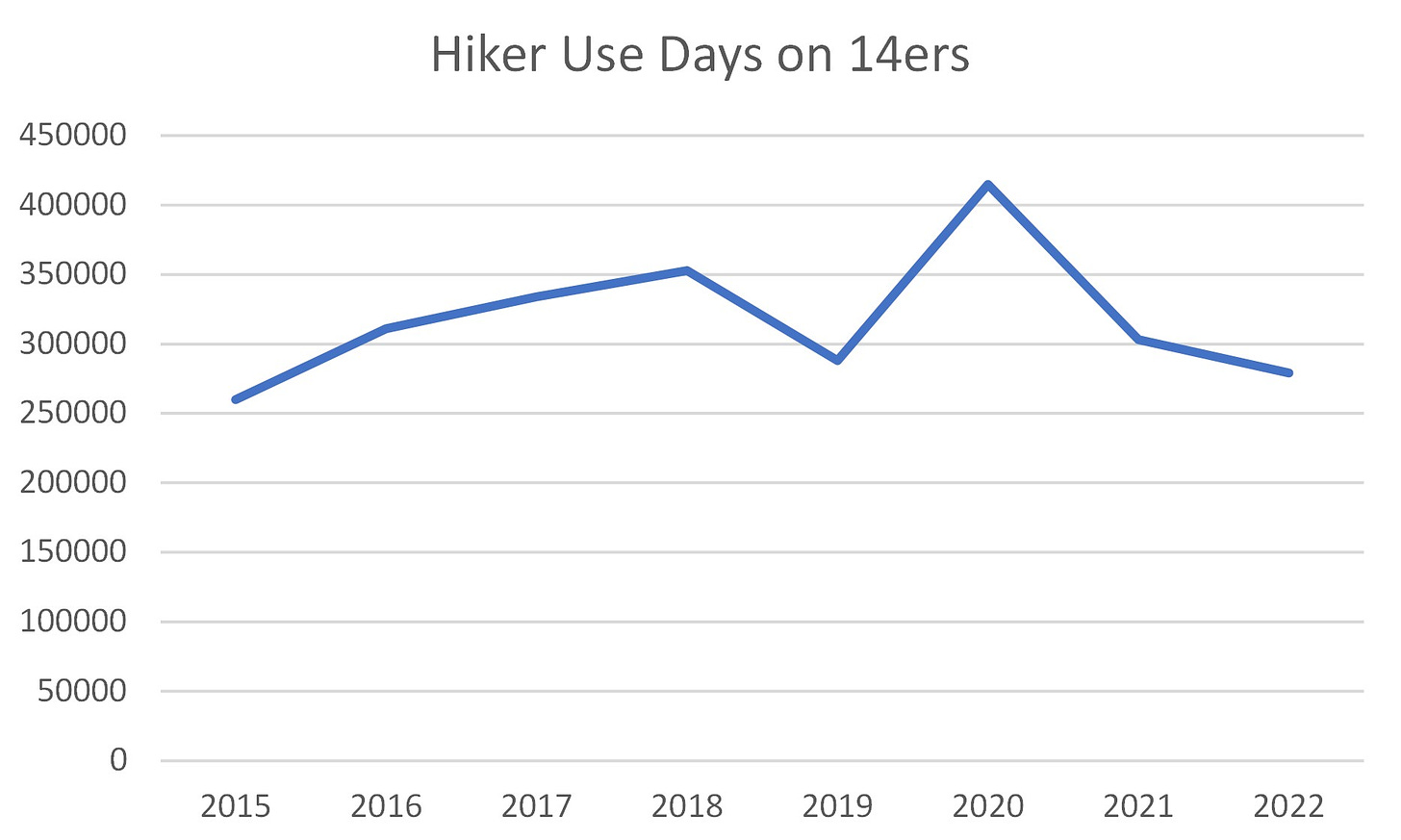

According to the report, 14er visits are down by a third in the last two years, and 8% during the 2022 season alone, illustrated below:

For the past two years, I’ve been questioning whether we are looking at a kind of mountaineering market correction after the COVID boom, or a bigger shift. I’m confident we now have our answer:

Hikers are being fenced off of the state’s high peaks, full stop.

Whether you believe that to be a good thing is a matter of debate. It’s something I’ve weighed in ther articles, I won’t repeat my arguments here.

Worth noting: 2022 numbers would have been more dramatic, if not for some hiccups with DeCaLiBron loop access the prior summer. Hikers returning to that trail stopped the decline from being even more dramatic.

CFI director Lloyd Athearn says it’s tough to point to any one specific specific factor driving the change.

“It could be a bunch of things… could be issues related to inflation, could be things such as demographics,” Athearn said. “Maybe what we’ve seen is a bulge in popularity. That we had an influx of residents and tourists who are more in younger millennial generations that were able to get out. And maybe they have more demanding jobs, or they’ve got kids, or they just aren’t as able to get out and do stuff as much.”

Whatever the specific cause, Lloyd is predicting a further drop in visitors in 2023 — pointing to land access issues and an immense snowpack that could push back the start of summiting season for more casual climbers.

I’ve long been reluctant to get into the predictions business with hiker behavior, but in this case I wholeheartedly agree. There’s more than enough data to show that this is more than just a correction from the oddity that was 2020.

What worries me here is whether a hidden ecological problem is now festering; one that could be nearly impossible to detect and solve.

Does Someone Need to Check on the 13ers?

I’ve spent thousands of words debunking the idea that raw visitor numbers translate directly to environmental damage. Lloyd himself points to the example of Quandary peak, where CFI’s trail rating improved from a C+ to an A- while visitor use more than doubled.

That said: the last decade has been an extremely overwhelming time for many small mountain towns who find themselves overloaded by sheer visitor numbers. Towns like Alma that once lobbied for laws that brought in more adventuring tourists1 may now feel saturated by very crowds they sought. They may blame high profile 14ers for the problem, and feel the compulsion to crack down, regulate, or otherwise push those visitors away.

“What I think is the worrisome trend is some of those communities saying oh, 14ers are overrun. Let’s push people to the 13ers. And that for me sets up this ecological nightmare where we’ve spent almost 30 years trying to build out a network of good trails on the 14ers, which is where people wanted to go. And now we’re going to replicate the same problem of just throwing people into areas where there are no planned trails and people are just running straight up a hillside.”

Put another way: driving people off of the well built, easy to monitor trails and into the fragile tundra may not be the best move for the environment.

Problem is: there could be other remote trails in pristine places, getting absolutely trampled as you read this article. We would have no way of knowing. The reason CFI’s data is so good, is because there are (relatively) few 14ers.

Woe to the enterprising conservationist who wants to start the Colorado Thirteeners Initiative. There are hundreds of 13ers, and more than 3,400 named mountains altogether. You can’t track them all.

“I think the place that one would want to start is looking at some of the centennial peaks,” Lloyd said. “So depending on whether you’re using the 53 or 58 — rounding out the remaining 40 or so peaks to 100, to sort of see: what are the use patterns out there?”

Even if someone did go down that road, it would take years to gather enough meaningful data to draw conclusions, detect a problem, and do something about it.

In the past, I’ve posed this controversial question: would be worthwhile to make a few peaks into a kind of sacrificial lamb — drawing in less experienced hikers and concentrating foot traffic into a place equipped to handle it?

The big 5 14ers did this job, and they did it well. I wonder if it’s time to take a step back, and reconsider our approach

Meantime — I think the best thing that we can do as a hiking community is to keep an eye out for developing problems, but also serve as good stewards. If we create a more welcoming environment for newcomers in the outdoor space, there’s a greater opportunity to pass on safe and conscientious habits.

If you enjoyed this article, consider a free subscription to Cole’s Climb for more independent reporting on the outdoor community.

Sharing is also a huge help if you like what you saw here! (bonus goat pic below for reading the whole thing.)

I address this again in my previous article, “The 14ers Aren’t Trails.” Here’s the excerpt in question:

’Back in the aughts, Alma was lobbying for liability protection for property owners (Keske & Loomis, 2008.) The town sits right next to the popular DeCaLiBron loop, which in turn sits on top of a big patchwork of mining claims. At the time, the town worried that if the claim-owners cut off access, they’d lose a ton of tourism revenue.

During a half-season trail closure, more than 20,000 visitors were lost. But the town didn’t seem to notice the difference.

“It's hard to tell if we were impacted by lack of hikers. The fees that

are collected at the trail head are used to maintain the facilities

there. The less users, the less maintenance required. As far as local

businesses, we were just coming out of COVID. Retailers were seeing an

increase of people who were happy to be out and about.”

-Nancy Comer, Town of Alma Town Administrator’

Sad.

https://deerambeau.substack.com/p/sober-is-better-part-5-solitude