The 14ers Aren't Trails. The Sooner We Stop Thinking of them that way, the Sooner We can Save them

“It’s sort of a quality over quantity. some places, that’s how they market themselves.”

DENVER, CO — September 15, 2022

The 14ers — mountains over 14,000’ tall, if you didn’t know — are very crowded. The community has been quite divided over what methods should be used to help protect these alpine environments.

To get a better idea of what the best path forward may be, I spoke with Doctors Catherine Keske and John Loomis. Their research1 on these peaks is the bedrock beneath a lot of conservation decisions that shape our recreation experience today.

They have fascinating perspectives that I’ve tried to boil down for you in this article. To start, I need you to at least entertain an idea that may sound ridiculous on its face:

The 14ers aren’t trails, at least not in the conventional sense.

The Rundown:

Just because a trail can hold a certain number of hikers, doesn’t mean it should

You already pay to hike 14ers. Paying a bit more could actually increase the total value you get out of the experience

Are 14ers more like ski resorts than hikes?

Mountain towns depend on recreation for tourism dollars, but many of these places now suffer from “over-tourism”

Getting people to choose other peaks for hiking, is a fool’s errand

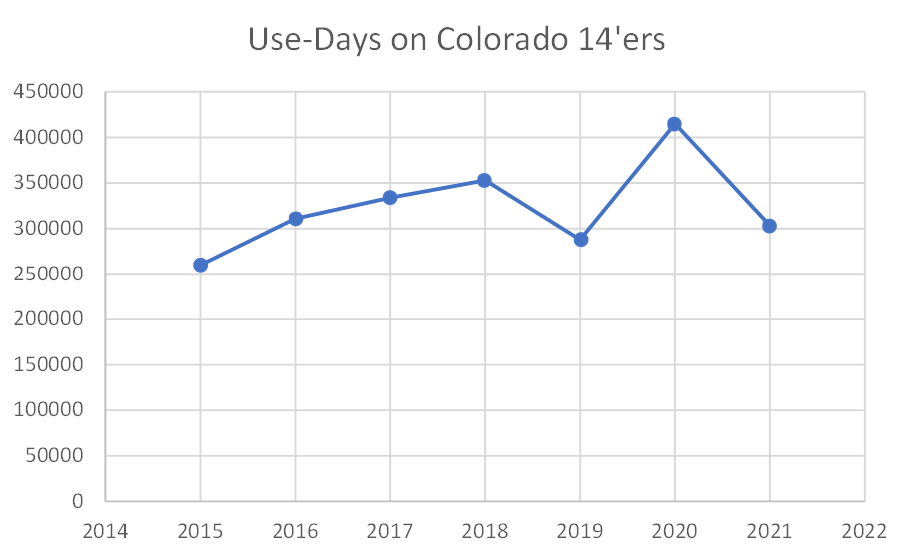

I showed you this graph a few weeks back, marking a huge drop-off in the number of people climbing Colorado 14ers:

In 2021, there were 112,000 fewer use-days on these popular peaks. Meteorologist Chris Tomer and I wrote a team-up article breaking down the data from the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative, or CFI, and made some predictions about what this means for next season.

Sometimes though, hard data doesn’t tell the full story.

2021 saw a massive crackdown on illegal — and frankly dangerous — parking along Steven’s Gulch. As a result, way fewer hikers tackled Grays and Torreys Peaks that season. According to CFI: around 10,000 fewer visitors showed up. Problem solved, right?

Not so fast.

I took this picture on August 27th, 2022, around 9:30 in the morning. Hey, if you were summiting around then, I got your picture! You, and all 128 of your friends…

I say that because I count 129 people in this photo. If you’re reading this on your phone, you might have to squint a bit to get the full effect. Every time I look at this picture, one word jumps to mind:

Crowded.

I wound up reaching this vantage point of Grays and Torreys via another path. I could count the number of other hikers I saw along that trail with on hand.

When I reached the ridge, I felt like I was standing in the staff only area at Disney World, peering over the fence at the guests milling around the park. The entire trail unfolded before me from peak to parking lot, like a long queue for a tourist attraction.

This may be one snapshot of one day on one peak. But the plural of anecdote is data. And these trails certainly don’t look any less busy.

Something Beyond Hiking

More than a decade ago, Doctors Catherine Keske and John Loomis predicted a future of paid 14er access, with uncanny accuracy. They’ve done extensive studies on these peaks, covering everything from economic impact to crowding.

Possibly their biggest conclusion is one that should give pause to everyone pushing the “fee” model: 60% of climbers are only interested in climbing 14ers. If they can't climb their chosen peak, they probably wouldn’t climb at all. But they're not giving up easy (Loomis & Keske, 2009, page 6.)

To this group, the hiking experience isn’t just about feeling solitude, or being in nature. That may be part of it. But ticking a box off a list definitely factors into the equation. A crowded trail doesn’t deter them. To a certain extent, neither does cost.

You Pay a lot to Hike 14ers, Actually

Do you know how much it costs to climb a 14er? Beyond fees or registrations, there’s gas to get you there, provisions, gear, and the occasional celebratory beer and burger after the fact.

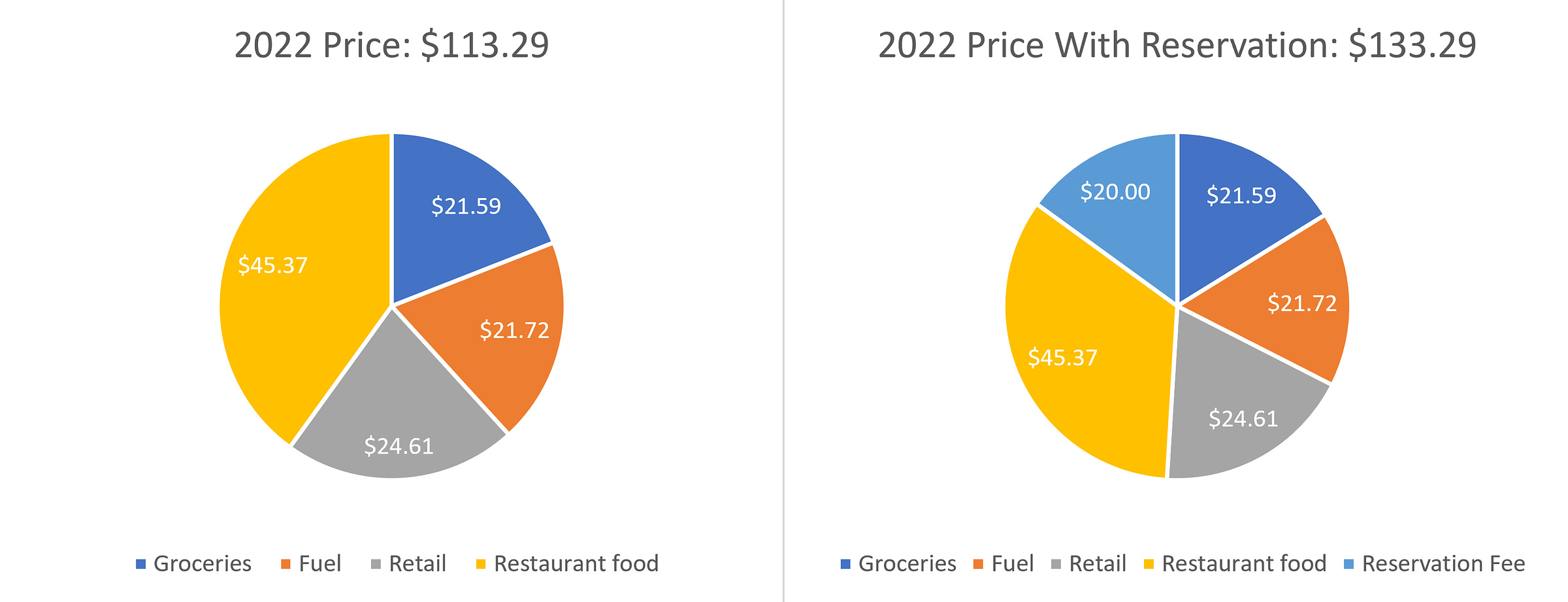

A different study determined the average hiker spends $115.48 within 25 miles of the peak they plan to climb, and $168 within the state of Colorado (Loomis and Keske, 2008.)

This number includes lodging, car rentals, and campground fees, partially pumped up from out of state travelers, or metro-area hikers who want to base themselves closer to their destination. Since I’m talking about the typical day-trip mountains, I removed these expenses from the price estimate before I adjusted for inflation.2

At time of writing, you’re shelling out roughly $113, per person, every summit attempt. The chart on the right includes the additional per-person fee, if a visitor pays for one of Quandary’s controversial parking permits.3 Turns out, it’s the least expensive part of your trip. Most of us spend more on gas, or trail snacks.

“Value Transcends Just a Market Price”

Hikers are clearly willing to pay something for the experience. A lot of us are just uncomfortable with the idea of needing a permission slip to go outside. Loomis and Keske skirted this problem by asking visitors what total cost they’d be willing to pay, and whether any price would lead them to seek out another mountain instead.

“We weren’t necessarily being tricky. And didn’t necessarily say it’s for a fee. We were literally looking at willingness to pay more. because when we look at value, value transcends just a market price, so to speak,” Keske said.

“We were really more interested in the value of the resource to people who were accessing the fourteeners.”

The price that some would shell out is absolutely staggering. I won’t say how much, because honestly, I don’t want to give Summit County any ideas.

But it raises an interesting point: even if you’re against fee access and reservations, there is still a financial value you place on the experience. It’s not so different from how you’d budget for a day at the movies, or a theme park.

The Epic Pass Paradigm

Let’s leave the 14ers behind for a moment to talk about a different kind of outdoor recreation: skiing.

Like hiking: once you have the gear, there’s a free way to enjoy the sport, far from other people. It just requires a bit more skill and effort. But that’s not how the majority of riders participate. Most activity is concentrated on a few popular peaks with strong infrastructure, designed to make access easy.

Of course these days, few people would think twice about forking over $50 for a lift ticket. Most resorts in Colorado charge between $170 — $200 for a single day’s worth of riding. Like the fourteeners, resorts can easily get overcrowded.

But over the last couple years, the industry — and its customers — seem to have hit a breaking point. During the 21/22 season, Vail decided to sell its Epic pass for a big discount. The result was far more visitors than mountain infrastructure could handle.

“That was the complaint last year with the Epic passes, right? you saw the dissatisfaction there, you know. Clearly, carrying capacity was greatly exceeded.” Loomis said. “They had these passes too cheap, and unlimited sales.”

“Even Disneyland and Disney World have a carrying capacity. And they shut the entrance down.”

Tickets were cheaper, sure. But riders were buying a watered-down version of the same product; paying less, but also getting less. How did the ski resorts tackle this?

Upgrading Infrastructure

There are two ways to fix a carrying capacity issue. The first is to build up infrastructure so that a place can handle more people.

At a ski resort, this looks like installing more high speed lifts with bigger chairs, expanding parking, and hiring more staff. On a 14er, the equivalent would be the work CFI does, hardening trails to handle more foot traffic.

Of course, just because a mountain can handle extra visitors, doesn’t mean the experience will be pleasant. That’s why some resorts are starting to opt for the second approach.

Controlling Access

Let’s keep our Vail example in mind: this season, the company announced plans to cap the number of lift tickets sold on a given day across all of its mountains. Arapahoe basin is taking things even farther. For the second season in a row, it will cap both lift tickets, and season passes.

Now, visitors aren't just paying to ride. They're buying a degree of exclusivity. Shorter lines. Fewer people. Loomis argues that on the 14ers, reservations or parking fees accomplish the same thing; that your total trip cost may go up4, but you're getting a more valuable experience.

“It may in fact be total benefits is going up to the users because there’s less crowding and congestion. And so from the standpoint of the Forest Service, less cost, and there’s higher benefits to the user,” Loomis said.

A fair critique of this argument: it’s a lot harder to see what your money gets you on a 14er. At a ski resort, your ticket helps pay the staff, generate the electricity to run the lifts, and buy the equipment needed for snowmaking. At Quandary, there’s a Porta Potty, and the implication your money is helping to maintain the trail.

For what it’s worth, I reached out to CFI to ask whether any of those reservation fees go toward trail maintenance. The short answer is no. According to Executive Director Lloyd Athearn: several local governments help fund their trail restoration work. Frisco and Breckenridge kick in. Summit County does not — whether through reservation fees, or otherwise.

Still, Loomis argues the financial benefit may extend beyond the mountain and into the après experience as well. With fewer customers flooding through the doors, nearby restaurants theoretically have better service.

Before you suggest this could choke tourism-dependent mountain town economies, Loomis addresses that point too:

“There may be lower economic impacts, you know. Fewer beers being bought in Alma and Breckenridge and so forth. But my understanding is that a lot of these places have sort of over tourism.”

“Over tourism?” I thought, “That seems unlikely. I wonder what the town of Alma would have to say about that.” I reached out to the local government to find out. Before I show you what they had to say, I want you to keep something in mind.

Back in the aughts, Alma was lobbying for liability protection for property owners (Keske & Loomis, 2008.) The town sits right next to the popular DeCaLiBron loop, which in turn sits on top of a big patchwork of mining claims. At the time, the town worried that if the claim-owners cut off access, they’d lose a ton of tourism revenue.

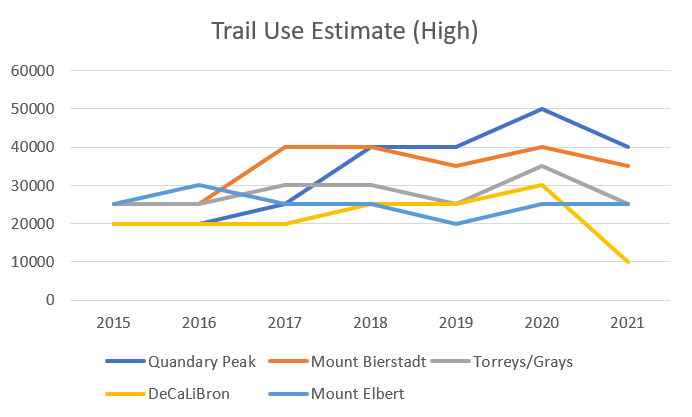

Now take a peek at this:

That yellow line is DeCaLiBron — Alma’s theoretical money printer — going offline. During a half-season trail closure, more than 20,000 visitors were lost. But the town didn’t seem to notice the difference.

“It's hard to tell if we were impacted by lack of hikers. The fees that

are collected at the trail head are used to maintain the facilities

there. The less users, the less maintenance required. As far as local

businesses, we were just coming out of COVID. Retailers were seeing an

increase of people who were happy to be out and about.”-Nancy Comer, Town of Alma Town Administrator

Other mountain towns are having different versions of the same problem. There’s just not enough places to live, to support the staff that businesses need in order to handle so many tourists. Perhaps mountain towns have been over their carrying capacity for ages, and this change is just a market-correction.

“The Magnetic Draw of the 14ers is Quantifiable. And it’s a Big Number.”

Of course, it’s possible to believe these mountains are crowded, without thinking a reservation system is the answer. Keske also suggests encouraging some hikers to seek out other destinations, like the 13ers.

“You will always have people drawn to fourteeners because they are iconic. But it’s not a bad strategy to suggest alternative hikes. Or alternative lists. And alternative experiences, especially if you’re seeking solitude.”

But there’s a limit to what can be accomplished here. As I mentioned earlier, only about 40% of all the hikers surveyed would even consider going to a different destination. Even so, a lot of that group would still pony up the extra cost to climb their chosen 14er. The magnetic draw of the 14ers is quantifiable. And it’s a big number.

Both Keske and Loomis understand and acknowledge that these peaks have a “special” quality that makes them non-fungible outdoor experiences (no Outside Magazine, not like that.)

If you want to get down to base economics, this is a supply and demand problem. There’s a set supply of 14ers, and an ever-increasing demand from people who want to climb them. Even if you try to create new parks, trails or outdoor experiences, research dictates the overwhelming majority will not accept them as an alternative.

The 14ers Aren’t Trails — So How Should We Treat Them?

Perhaps these special peaks fit into their own class of outdoor recreation, totally distinct from hiking. Perhaps paying a little more for our trips is a fair trade to buy some breathing room. Perhaps this can keep the mountains from devolving into full-blown tourist attractions. Is this really all that far removed from how we handle our other outdoor hobbies?

Wherever you fall in the debate, these decisions should be made with a ton of community feedback and oversight. In an earlier article dressing down the Colorado Campsite reservation system, I raised a similar concern about going too far with paid access.

It bothers me that Summit County operates Quandary Peak like a tourist attraction, without paying any of that money back into maintaining the trail. I find myself reaching the same conclusion State Senator Jim Smallwood vocalized in my earlier article:

“The idea is not to turn the state of Colorado’s outdoors into some profit center; for our state to gouge our citizens and visitors with a profit motive.”

Whatever solution we choose, we need to keep in mind the reason we’re doing all of this: to protect the iconic resources we love, for future generations to enjoy; not to needlessly commodify them.

I Want to Hear from You

How do you think 14ers should be protected? Do you think any action at all is necessary? Leve your thoughts in the comments down below!

And if you’re not already, consider subscribing to Cole’s Climb. This weekly publication features everything you’d want in outdoor media: great stories and views, interviews with real people working to improve our ecosystem, and news that actually impacts you.

Normally I try to include any research documents I reference in my writing so that you can read them for yourself, if you feel so inclined. Because they’re published in academic journals who charge money for people to read them, I can’t just embed them here. But I can provide you with a link to look at Dr. Keske’s author copies, which she has available on her website. All of my sources are linked on that page.

Prices are much different now, than they were when the study was first conducted. Rather than broadly multiply the 2008 totals Loomis and Keske arrived at, I used category-specific inflation metrics from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Specific metrics were available for groceries, gas, hotels, and food away from home (restaurants.) For retail and camping fees, I used the estimate of the core commodity inflation, which was 34.99% over the time period.

Again, this number will appear lower than the pre-inflation numbers reached in the 2008 study. Keep in mind: lodging costs made up a huge chunk of that earlier estimate.

Quandary’s permit system is tiered, so I needed to make an estimate here. Weekend car permits are $50 per vehicle, but according to survey data presented in Summit County’s Visitor Use Management Plan, hikers tend to drive to the trail head with an average of 2.5 passengers per car, hence $20 per person.

You can also buy a weekday pass for $25, which would come down to $10 per person. Or park in the airport lot and take the $15 shuttle. Reservations could run you anywhere between $10-20. I decided to steel-man this point with the most expensive estimate I found to be reasonable.

Using Quandary Peak as an example, the reservation fees raise the total trip cost an average of 17.65% based on our earlier calculations.

Great article. The idea of "paywalling" them is sad to me, as that is quite literally gatekeeping nature based on income. I can't help but always come back to the defunding of the Forest Service — and perhaps just a simple registration system. You can only hike if registered, but registering should be free. Ben plans to drag me up Mt. Wilson next year — next to but not the same as Wilson Peak. I've never "bagged a 14er" and don't care about it. Some of these 14er hikes don't even look all that interesting, and I can't connect with what's so special about climbing one.

That said, people obviously connect with them! Looking forward to reading more.

This is a fascinating post and gives me a lot to think about! I don't have a strong opinion, because I'm not driven to summit 14ers (I've only made it up Sneffels and Handies), and I haven't experienced the crowding. I'm doing Wilson Peak this weekend, and if I end up writing about it, I'll be sure to link to this post!