Can't Get a Campsite Reservation? Shocking Audit Uncovers Possible Reasons Why

Questionable closures, preferential treatment and potential for abuse may have clogged campsites and shut out visitors

DENVER, CO — June 23, 2022

If you’ve been having a hard time finding a spot to camp in Colorado: problems with the campsite reservation system could have played a role, according to a report from the Office of the State Auditor.

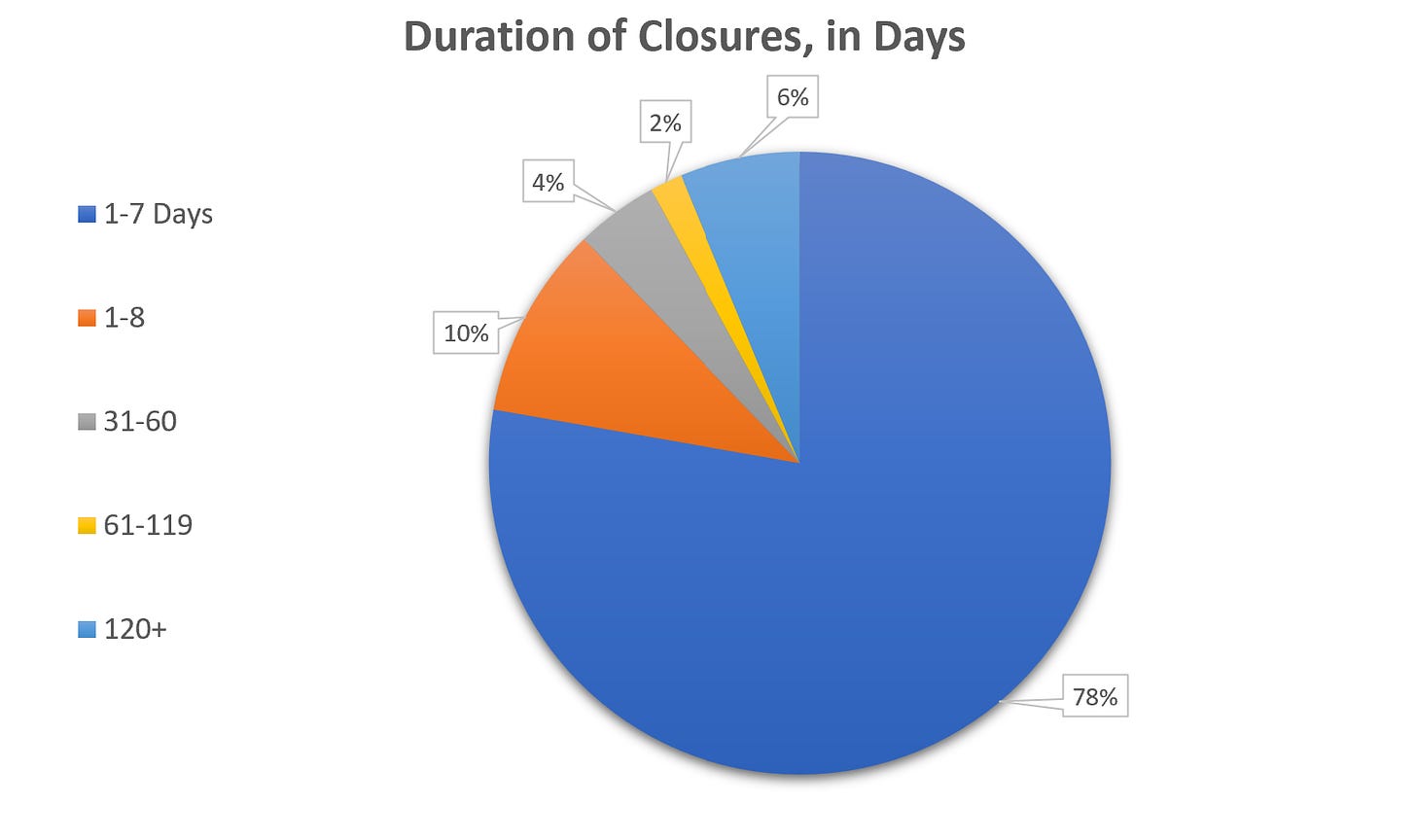

Auditors found Colorado Parks and Wildlife, or CPW, listed more than a third of all campsites closed at some point throughout the 2021 season. In total, these closures deprived potential visitors of approximately 53,100 reservation-nights1 (Read: opportunities to camp.)

Many of these closures were likely legitimate. But the report found the closure system was, in some cases, being misused to resolve customer service issues.

The audit also uncovered a risk that staff members could abuse the system to give friends and family priority access, or even pocket your camping fees.

The ordeal leaves local governments — and their constituents — with much to consider as more Colorado destinations move toward reservation and timed-entry models.

As always, I want to be as transparent as possible with my sources. The audit report I’ll be referencing throughout the article is available here for you to read:

You can also listen to the entire audit committee hearing where the findings were discussed. The parks audit starts around the 10:39:00 mark.

How these Closures (Should Have) Worked

CPW manages reservations through software called the “Integrated Parks and Wildlife System,” — IPAWS for short. The management program gives park staff and volunteers broad authority to close campsites for a variety of reasons. For example:

Special events

Emergencies (in which guests are unable to leave the park)

Maintenance

Housing staff members or volunteers

From my understanding: closed and reserved campsites would look exactly the same for a guest using the system to book their trip.

The audit found not all closures followed the guidelines, and a lack of record keeping means it’s impossible to say how many closures were legitimate.

How the Closures Impacted You

You’ve probably heard of airlines and hotels deliberately overbooking, knowing some people won’t show up. According to 28 of the 29 CPW park managers2 who replied to the audit survey: staff were doing the opposite.3 Managers said staff closed off extra sites so that if campers set up in the wrong spot, arrived on the incorrect day, or wanted to extend their stay, they would have extra room to house visitors without conflict.

CPW also disabled the system’s “no-show” function. This would have made campsites available to more potential campers, if the original reservation-holder didn’t show up for check-in. This means some sites that could have been re-booked simply stood empty. The reason given was to prevent customer service challenges in the event those campers did show up later into their reservation.4

While I understand the rationale — it’s a bit like a restaurant keeping a table open all night, even after the couple they were holding it for blew off their reservation. All the while, other guests crowd around the hostess stand, growing irritated.

These decisions seem to be driven by a goal to placate potentially difficult visitors and spare staff from having unpleasant conversations with guests. This may have made the parks easier to manage, but potentially kept visitors away in the process.

The Potential for Abuse

The audit also uncovered a weakness in the reservation system that an unscrupulous staff member or volunteer could use to run a shake-down scheme on both you — the park guest — and CPW itself. It could go something like this:

The hypothetical staff member uses the IPAWS system to close several sites

A camper arrives without a reservation

The staff member collects site fees from the guest in cash

The staff member directs the guest to a closed campsite, and they never show up in the system

The staff member keeps the cash, and the guest is none the wiser

Some of you who have visited one of Colorado’s parks may now find yourselves wondering whether the site fees you paid went to upkeep, or someone’s pocket.

State Senator Jim Smallwood — Chair of the Legislative Audit Committee — underscored this risk during the audit hearing, stressing the importance of maintaining integrity and confidence in the system.

“This is one of those areas that is really just prone to that, meaning: ‘this campsite is closed — hypothetically. No reason given — hypothetically. But guess what, if you — hypothetically — give me X amount of money in cash, then this can magically reopen.’ And I don’t think any of us want to see that. Because these folks are out, away, right? There aren’t security cameras like a casino or a convenience store or something like that. It’s just really, really important to me that integrity that is built in due to the processes and policies and procedures that you have, is maintained.”

HUGE DISCLAIMER

When I spoke to the members of the audit team, I asked them point blank if they had any specific examples of abusive behavior.

“We did not find evidence that actually occurred,” said Team Leader Cariann Ryan. “If we had, we would have put that in the findings.”

I want to be very clear on what that means: neither I, nor the audit team are alleging an incident like the ones described above have occurred.

Director Dan Gibbs of the Colorado Department of Natural Resources also addressed this in the hearing: “If any of our staff is aware and thinks fraud is going on, they need to report it, period. And we will investigate that.”

Still: the team does point out the system — as implemented — could easily be taken advantage of. The very nature of this exploit also makes it virtually impossible to prove or disprove.5

“CPW staff do not analyze aggregate data related to closed sites to monitor how those sites are used or ensure all revenue generated from the use of those sites is properly submitted and accounted for in IPAWS and the State’s accounting system.”

In other words: no one is going around and inspecting the closed sites, making sure they’re being used properly. If someone was using IPAWS to create off-the-books campsites, there’s no fail-safe to catch them.

Also: the scenario described above is alarmingly close to a method some park managers say staff routinely use to check in guests:

“14 park managers stated that if prospective campers arrive without a reservation, staff will either use a closed site, or close a site in IPAWS and then let campers use the site, rather than entering a reservation into IPAWS.”6

Staff told auditors this is easier than entering all the customer information into IPAWS. But in these situations, there is no data on how much guests paid to stay. One manager seemed to indicate staff were charging flat fees in these situations — not the actual site cost.

“There is Definitely a Risk that an Employee Could Close a Site for Personal Gain.”

This response came from one of 11 park managers who expressed concerns the closure system was being exploited — either for individual profit or helping family and friends secure sites.

“This is another type of fraud where you’re using something of value as a state employee or agent of the state, to benefit your friends and family,” said Dan Fugate, Director of Communications & Quality Assurance with the Office of the State Auditor. “The department does take this seriously too. They understand the risk.”

Whereas no one has currently come forward alleging payment fraud, one park manager told auditors they had seen staff use the closure system to help family and friends.

These aren’t new issues either; they were flagged 14 years ago. A 2008 audit recommended CPW lay out a clear policy about site closures, including:

A short-list of staff authorized to make closures

Special documentation of closures

Laying out the exact circumstances where closures, discounts, and complimentary stays can be granted

The current investigation concludes that based on the responses they got from park managers: these recommendations never came to pass.

Not All Visitors Paid the Same to Stay

If you visited one of these parks, there’s a decent chance you didn’t pay the same amount for the same services. Remember those flat camping fees I mentioned earlier? These appear to be part of a pattern of improper discounts and refunds picked up in the audit.

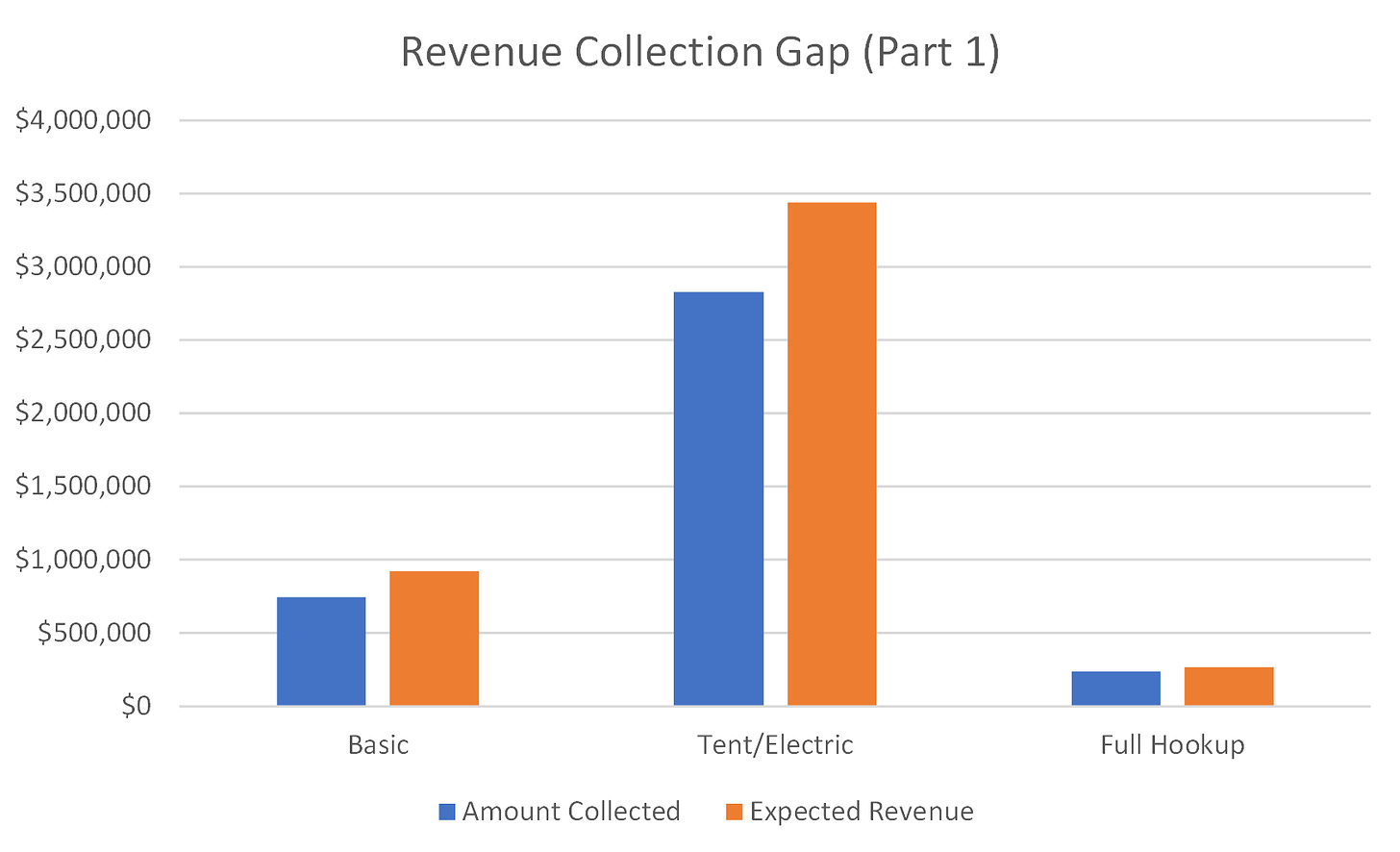

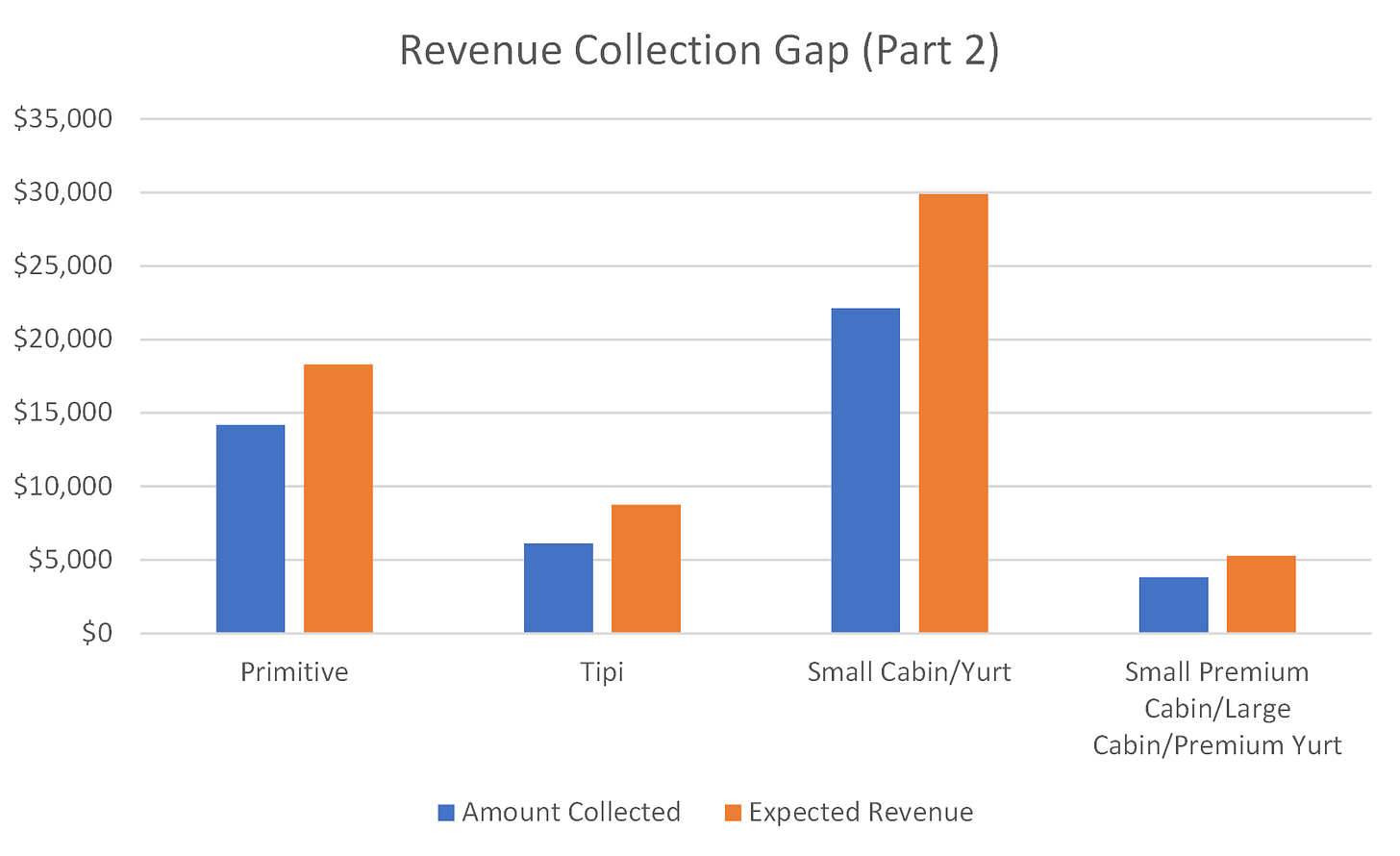

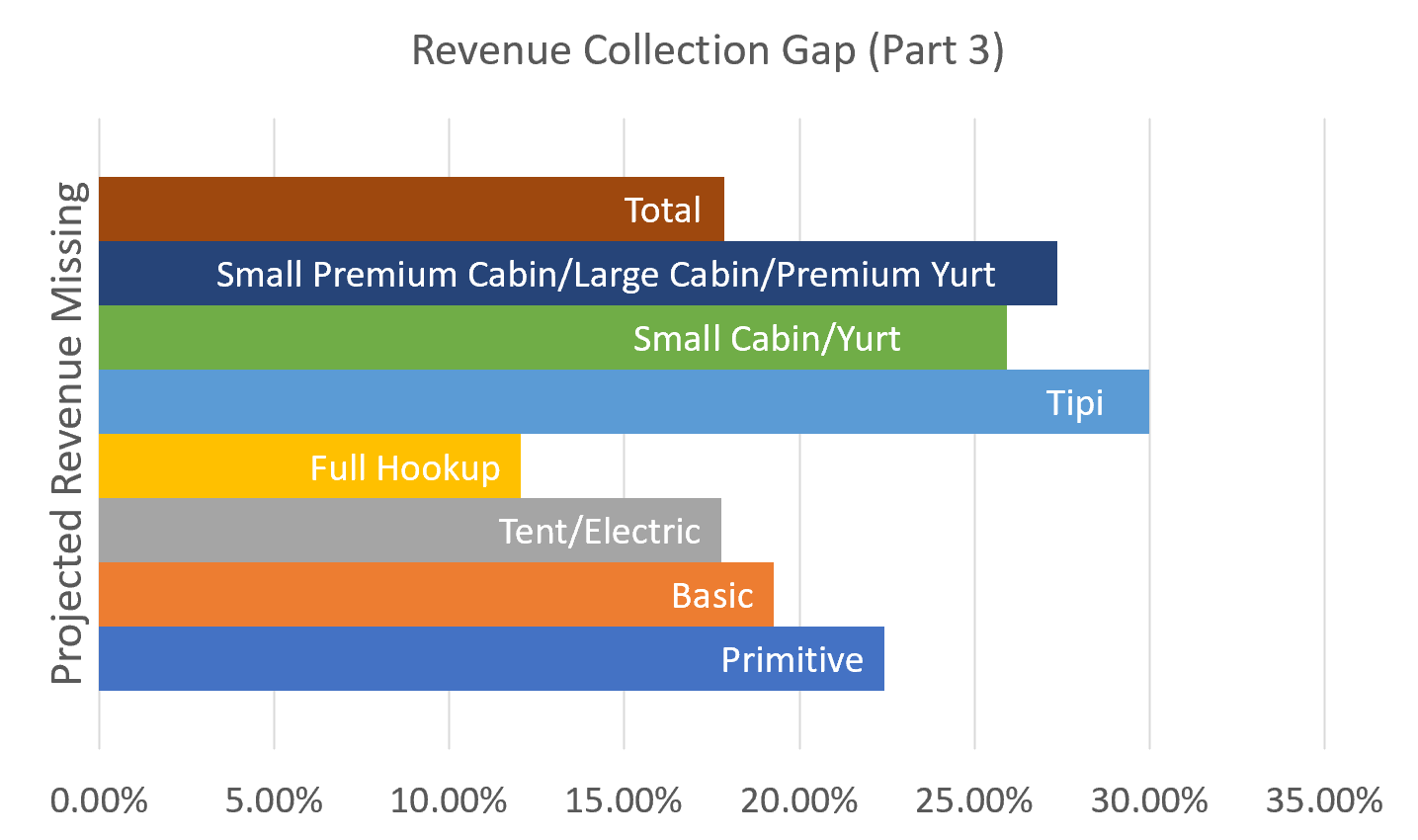

The orange bars represent how much money the sites should have taken in, based on the price structure, and number of visitors. Blue represents how much money they actually made.

That’s a pretty noticeable gap.

By the way — I split off basic, tent/electric, and full hookup camps into their own graph because they raked in so much more money, they made the other bars too small to read when they were all put together.

With all this finance talk, I’m sure your eyes are starting to glaze over. But this discrepancy isn’t about the money, really. (Okay, it’s not just about the money.) It’s about treating all campers equally. Mr. Fugate — from the Office of the State Auditor — came back to this point several times throughout our discussion of the findings: it’s about equitable treatment of state park visitors.

If discounts are being offered, they should be made available to everyone — especially with CPW running a budget surplus for the last 2 years.

Again, we’re not just talking about a few bucks, either. This is $836,000 — almost 18% of all the site fees for an entire year — that’s only partially accounted for.

Some of this can be chalked up to legitimate park discounts — which came up in the hearing. For example, approximately 4,000 nights in 2021 were booked by Aspen Leaf or Columbine passholders. But these passes only grant a discount of $3 per night and would account for just $12,000 of the discrepancy.

Parks are allowed to offer discounts for several other reasons. However, these discounts need to be approved in writing by one of CPW’s four regional managers and applied to all guests. Auditors found that despite this requirement, the IPAWS system allowed virtually any staff or volunteer make price reductions or fee adjustments.7

“The idea is not to turn the state of Colorado’s outdoors into some profit center; for our state to gouge our citizens and visitors with a profit motive.”

During the hearing, Senator Smallwood made it clear that the financial side of the audit is an important but ancillary issue; particularly after CPW reported a budget surplus of $7 million in 2021.

From my interpretation, the primary concerns are framed around visitor experience:

Giving as many people access to the outdoors, as easily as possible

Ensuring visitors are treated equally, in terms of park pricing and access

Tightening systems to prevent bad actors from taking advantage of guests

CPW seems to be on the same page, officially and completely agreeing to all recommendations made by the audit committee.

"We appreciate the auditors’ review of CPW’s processes and procedures for campsite reservations, and are immediately working to implement the recommendations in the report," said Acting CPW Director Heather Dugan in a statement to Cole’s Climb. “The audit identified that CPW needs better processes and procedures to document and approve campsite closures for a clearly defined reason. Campsite closures are important management tools for our park managers, and we will continue to use closures when campsites are not usable (such as when covered in snow during the winter), during emergency situations like wildfires, and for volunteer camp hosts and trail crews."

When You’ll Notice the Changes

I echo concerns voiced by the audit committee and the Department of Natural Resources: that park staff were given broad latitude to decide who could camp, where, and for how much — without nearly enough training or oversight to ensure everything is above board.

Many of the issues brought up during the audit can plausibly be explained as staff trying to serve guests as best as they could, within the confines of a cumbersome system. More than a dozen park managers say they were never trained on the software. And 24 park managers say volunteer staff members aren’t trained either. Staff were instead directed to online training manuals and tutorials. But using them was not mandatory.8

State Senator Jeff Bridges even suggested CPW spend some of its surplus to discard the IPAWS system and make something easier for both guests and staff to use. But this poses its own challenge. CPW points out that few vendors are capable of tackling such a massive job.

The vendor who works on the system is currently busy with another project. CPW says it already needs to wait almost a full year before the vendor can work on fixing the permissions problem in IPAWS, which led to the closure and discount issues.

This would involve reprograming the reservation system to ensure only full-time park supervisors are able to close sites and offer discounts within the system. Because of the wait time: the feature won’t be ready until at least partway through the 2023 camping season.

Who knows how long a full overhaul would take?

CPW says the meantime: the re-booking function has been brought back online, and it has enacted new training requirements for IPAWS.

The agency also hired a full-time “Reservation Coordinator.” This person is tasked with keeping a watchful eye on site closures and cash flow to ensure fraud or abuse in the system only exist — as Senator Smallwood said — hypothetically.

“This monitoring could include routinely analyzing diagnostic/analytic reports containing campsite closure and payment data to identify suspicious patterns, such as higher rates of closures at certain parks…”9

The bottom line: state leaders and CPW seem to realize the problems that exist in the reservation system’s framework, particularly when so many people have access to it without proper training.

But taking back the reins and tightening controls will not be a quick or easy task. It could be some time before campers feel the impact of these fixes.

Lessons for the Future

One of the most obvious takeaways here is that problems like these are much easier to head off proactively, than to clean up later.

This is something counties and cities should be keeping in mind as they roll out new reservation systems for hiking access across the state. (By the way, I have a list of those reservation systems compiled for your use here.)

These local reservation systems are also beyond the purview of state auditors, making it especially important to keep a close eye on how they operate.

I Want to Hear from You

Have you had experience dealing with campsite, park, or trail reservation systems? Did you have a hard time getting a site? How do you think they could be improved?

If you haven’t had any dealings with the reservation system, clicking the heart button at the top of the page lets me know this reporting was valuable to you, and helps me continue to deliver valuable content to your inbox.

The number of available campsites, multiplied by the number of days in the season for which reservations are accepted

The audit team wanted to stress: the survey data gathered from CPW staff cannot reliably be extrapolated and applied to the park system as a whole

Audit page 16, paragraph 3

Audit page 17, paragraph 2

Audit page 16, paragraph 2

Audit page 16, paragraph 2

Audit page 16, paragraph 5

Audit page 18, paragraph 1

Audit page 21, paragraph 4

Love a deep dive!! I showed this to Ben and he was like, "this is why we only camp on BLM land." Hah!

Cole, I forwarded this interesting article to Bruce. He has been traveling state to state and camping throughout. Yes, he too has experienced issues with campsites and so obviously not just Colorado. Thanks for the heads up.