"Fire, Aim, Ready!" — The Alpine Amusement Unraveled, Part 2

An overnight change at Grays and Torreys highlights the downstream challenges of crowd management.

This written investigation delves deeper into the issues highlighted in the documentary, "The Alpine Amusement Park." Here’s a quick refresher from part 1:

Crowding is not a phenomenon brought on by the pandemic

More hikers do not necessarily mean worse trail degradation

All but two fourteener trails are unplanned bushwhacks

Do You Remember the Chaos?

The first time I hiked Grays and Torreys, parking was an absolute cluster-hug. Once the tiny trailhead lot filled up, you kinda just squeezed your car wherever it fit. I remember pulling in behind a sedan that had bottomed out, and didn’t dare go farther.

If it had been light out when I left the car, and I saw where I’d left it, I would’ve spent the whole hike worrying whether it had rolled into the ravine.

All these cars parked along the road also made it a nightmare to drive back down to the highway. Then, one morning, signs like these lined the signs of the narrow roadway:

As previously outlined: this trail started as a bushwhack built on an old mining road. The parking area sits on a postage stamp of land, surrounded by homes on remote private property, with no room to expand.

Private landowners weren’t the only ones taking issue with the clogging of Steven’s Gulch.

As early as 2019, Alpine Rescue Team — which responds to calls at Grays and Torreys — raised concerns rescue vehicles may have difficulty getting through in case of emergency.

Steve and Dawn Wilson are both public information officers for the group. They echoed my earlier conclusion from CFI data: trail use is steadily climbing in line with Denver’s growing population.

Alpine Rescue Team is shouldered with a tricky burden. Their coverage area is along the I-70 corridor, and among the closest to the metro area. It’s tasked with responding to some of the most popular destinations in the state of Colorado.

“The fourteeners that we have are the beginning1 fourteeners. Evans and Bierstadt, and Grays and Torreys aren’t the ones that are the last ones people check off, when they’re doing the list. It’s the first ones,” Steve said.

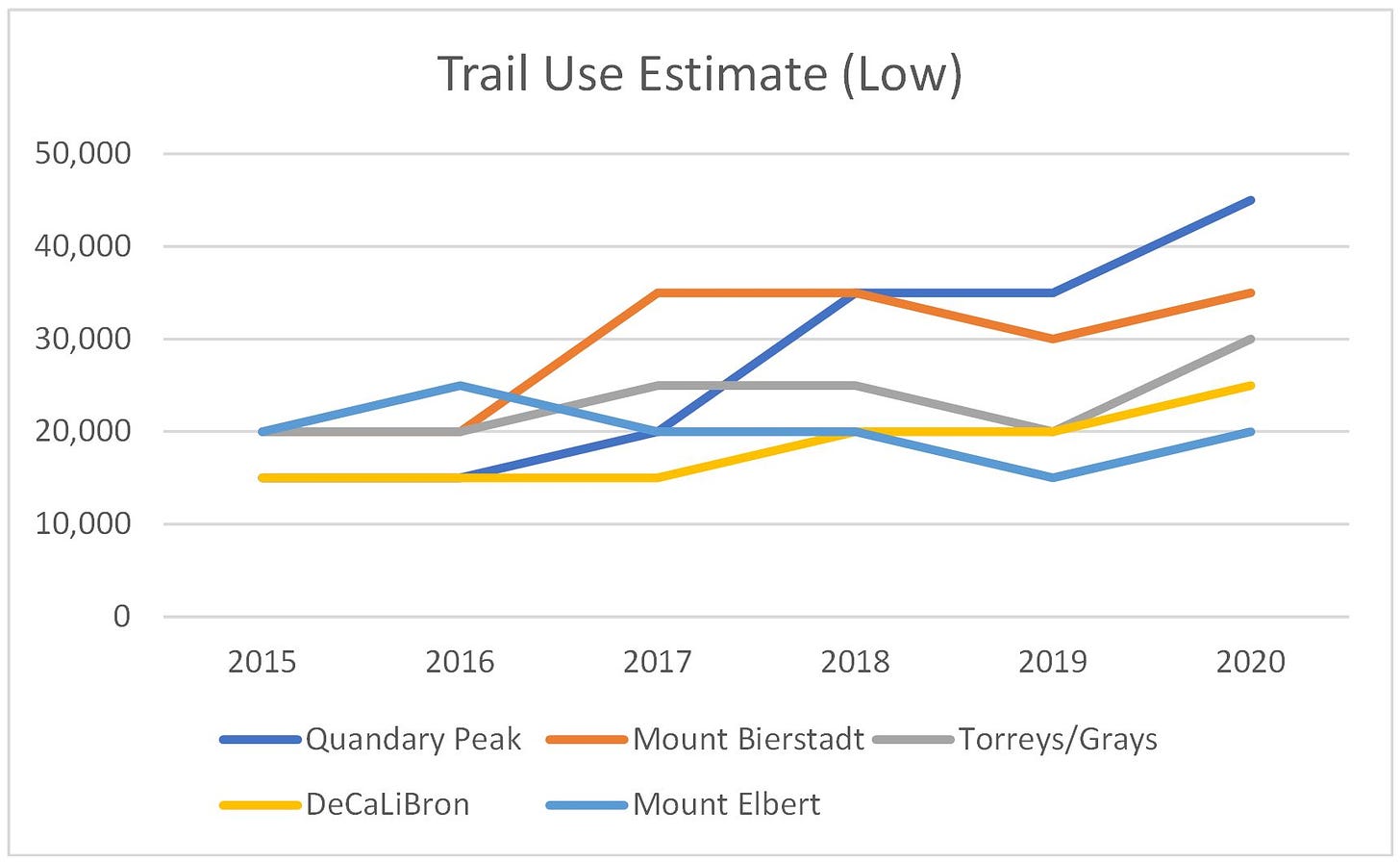

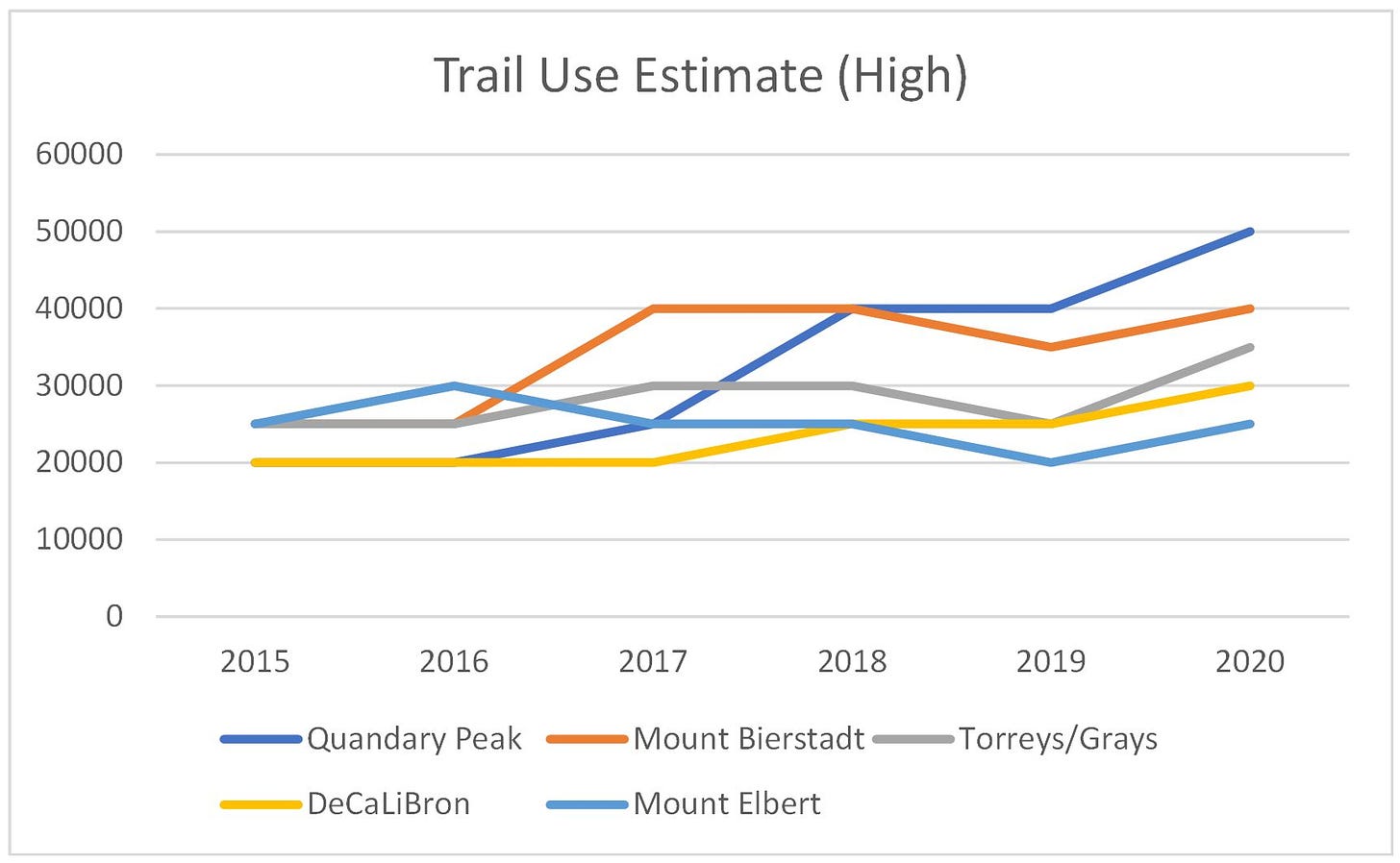

Exactly which fourteeners see the most attention vary year to year.

These charts refer back to trail use estimates from CFI.2 In my previous analysis, I focused on over-all hiker numbers each year. Here, I use the same raw data, but change the presentation to examine how different destinations rise and fall in popularity.

Notice that while the overall use trends upward, different peaks jockey in the rankings.

Elbert falls from the top to bottom of the top five in terms of use over the last five years. Bierstadt’s use declines as more hikers flock to Quandary.

“It can be trendy too,” Dawn explained. “If something was in our local newspaper or local broadcast of a hike to do, then we’ll see an increase there as well as families or individuals explore that area.”

But if visibility pulls visitors in, increased restrictions push them away. As I’ve previously covered: if you can’t find a spot in the Grays and Torreys upper lot, you’ll have to drive back to the overflow area, right off the highway. This adds an extra 6 miles to the hike, making for a 13-mile total trip.

Part of the appeal of this trail always seems to have been the ability for hikers to bag two fourteeners over a relatively short distance. That mileage puts Grays and Torreys out of “beginner” territory.

While this could reduce foot traffic in the short term, Steve predicts this change won’t be permanent.

“I think that that impact will drift away. As it becomes less of something hikers are aware of, people will park up there again. It will become busy again. It’ll be our hotspot one of these years, coming up again. People are not finished climbing fourteeners because the road seems crowded.”

“How Many People are Having a bad day on Those Mountains?”

Foot traffic matters to CFI. Not so much for rescue crews.

“It’s not how many people are on these mountains; it’s just how many people are having a bad day on those mountains. We only see the people who get lost or get injured,” Dawn said.

In some cases, having more people on the trail actually reduces the need for a response. This slightly counter-intuitive phenomenon is sometimes referred to as a “Crowd Rescue.”

“If it’s really crowded one day, we might not get called for injuries because there’s so many people on that mountain, they just help each other out. We’ve actually had that happen a couple times, where we get called for a broken leg on the summit of mount Bierstadt. By the time we get there, the person’s already down because all the people on the mountain have helped out.” Dawn said.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but I’ve actually done a crowd rescue. It was during my first traverse of the famous Knife’s Edge, along Kelso ridge.

This phenomenon is not unique to Grays and Torreys — or even just the Alpine Rescue Team coverage area.

Anna DeBattiste is with Summit County Search and Rescue. This team handles calls a bit farther from the Denver Metro area. But they happen to cover the most popular peak in the state: Quandary.

Anna tells me they see plenty of crowd rescues, too.

“A lot of Times, There are so many People up There, They’ll just Crowd Rescue the Person and We don’t even Need to Go.”

If you’re in trouble, you should be hoping the trail is crowded. A lot of people have this idea that a helicopter will swoop in to save the day, the second you call for help.

Truth is, you’re usually hours away from responders reaching you.

“We’re not sitting in a fire station waiting for the call to go out. We’re home or at our day jobs. We have to respond from wherever we are in the county. Then we’ve got to hike into you,” Anna said.

Broadly speaking, the “casual hiker” types that tend to flock to these popular destinations, are actually easier to help — and this is another point that seems counterintuitive until you think about it for a second.

Inexperienced hikers usually don’t know enough to get themselves into real serious trouble; their lack of skill quite literally protects them from getting into higher-stakes situations.3

Lost? Someone from the closest rescue team can probably guide you back to the trail over the phone.

Tired? Sit down and rest for a little while.

Compound fractured your leg in an avalanche during your backcountry ski trip? Eh, you might need a bit more help.

Of those scenarios, guess which one Summit County Rescue gets the most.

“We get most injury calls and lost party calls on Quandary. The trends in recent years are more lost party calls in the winter,” Anna said. “In the summer, we get more hiker injuries. Occasionally we get a big burly rescue of someone who has gone off the backside and become cliffed out or injured in technical area. But more commonly it’s just someone injuring themselves on the front side.

Parking Restrictions and Rescue Calls

Like Grays and Torreys, times are a-changing on Quandary as well. The mountain now has both paid parking, and a paid shuttle system during peak summer months.

According to Anna: the change hasn’t made a difference in the number of rescue calls they get. But it is easier to bring in, and set up their emergency equipment.

While calls haven’t decreased on Quandary, Anna says they also haven’t gone up anywhere else either. So if crowding, restrictions, and reservations are changing hiker behavior, it’s not showing up in rescue trends. This could be for a few reasons.

Hikers could simply be undeterred and ignoring the restrictions. There’s certainly data-based evidence of this in the Park Quandary reservation system; the topic of the next installment in this investigation.

If hikers are seeking out replacement trails, they’re not running into trouble — at least not in large enough numbers to show up on rescue teams’ radar.

One trend that has cropped up and I would be remiss to leave it out: Alpine Rescue Team says they’re getting more rescue calls on weekdays, rather than weekends.

I chalk this up to more flexible schedules, brought on by the pandemic. It may seem trivial, but these search teams are made up of volunteers who have other jobs and responsibilities. This means rescue teams will need to be sure their lineup also includes hikers with a variety of schedule availability.

Steve assures me they have a deep lineup. But this may be something for other, less well-staffed teams to keep in mind.

Search for the Weakest Link

Rescue calls, like trail use, are on an upward trend. But the evidence doesn’t point to this being crowding-caused. As CFI Executive Director Lloyd Athearn points out, there is some degree of safety in numbers.

“Isn't it better all-around to get people on trails that are easy to follow? There is probably some level of safety in numbers if something happens here, rather than just having people willy-nilly going through un-trailed areas without the experience to do so,” Lloyd said.

I’d argue the increase in rescues actually comes from something else entirely: a lack of preparedness.

“Somewhere along the line climbing 14 years went from sort of an avocation of mountaineers and climbers, to a very mainstream bucket list type thing,” Lloyd said.

As the profile of the average visitor shifts from the older and more experienced mountaineers, motivations change too. Hikers have access to more guidebooks, maps, and trip-planning resources than ever. But not everyone uses them.

There’s an argument to be made that hikers looking to tick a peak off their bucket list, may be more likely to push through for the summit when they should turn around.

That’s when you can create problems for rescue crews.

"We also have missions because people try to get to the top to take that picture. Even if they have altitude sickness, or lightning coming.” Dawn said. “It’s not worth your injury or your life just to get the picture on the peak.”

Aside from setting yourself up for a miserable time, doing so can also incur a risk of injury for the rescue team looking for you.

Steve puts it best:

“The one thing that’s not going to change is the mountain. The mountain will be here tomorrow. It’ll be here next week. It’ll be here in a year. There’s plenty of time to not risk your life today, to get that picture in the fog, in the rain, and in the lightning. Come back tomorrow or next week, better prepared, better equipped, with more knowledge. And you get a better picture.”

The True Impact of Crowding

If you watched the film, and read my previous post, I’m sure you can see the pattern. Raw numbers are far less important than visitor behavior.

The limiting factor isn’t the number of hikers or rescue missions. I’d argue the most pressing problem is also the most mundane: parking.

On Quandary Peak, Summit County met this rather boring problem with an unusual solution: they turned the trailhead into a bona fide tourist attraction.

In Part 3:

Summit County Government shares information I’m confident no one else has seen, laying out the inner workings of its “pilot program” for this busy trailhead. I’ll break down the numbers for you, and analyze whether this solution actually works — before we decide whether it should be replicated.

Subscribe now to ensure you won’t miss it!

And if you are enjoying this series, consider sharing with a friend who loves the outdoors:

Notice: Steve says beginning, not beginner. There’s a difference. He clarifies later in the interview that while difficulty is certainly relative, there is no such thing as a beginner fourteener. All should be approached with caution, respect, and preparedness.

Data methodology: these graphs are compiled from the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative annual use reports, which date back to 2015. 2021 Data is not yet available.

My mountaineering friend describes this phenomenon using the expression, “The more you know, the deeper you go.”