The Alpine Amusement Park — Exploring a Controversial Approach to Conservation

Popular hiking destinations are looking more like theme park attractions than trails. Here's how we both conserve and preserve access to the outdoors, without putting up turnstiles:

America’s most popular trails are dealing with a crowding problem. We’re moving into a strange era of lottery systems, tickets, and assigned visiting times to go out and access nature. But do these measures work?

In “The Alpine Amusement Park,” I explore a controversial crowd control model being deployed in Colorado, evaluate whether it actually works, and determine whether the results could — or even should — be replicated.

If you prefer to watch, rather than read: this piece also exists as a documentary, which is available for viewing here.

Part 1: The Devil We Know

Is it better to keep the problem of crowding concentrated where you can see it? Or does it benefit the environment to spread the problem around all of our trails and mountains?

Stay on the Trail!

Despite my best effort to secure my camera gear in the trunk, the bumpy ride up Steven’s Gulch managed to shake it loose. The tripod, my backpack, and I all jostled around in my jeep, bouncing over rocks and boulders.

After white-knuckling the steering wheel past a few steep drop-offs to the water below, I pulled into the tiny parking area. A car stood in almost every space, but I didn’t see another soul hanging around.

I parked near the ruins of an old mining claim, and stepped out onto dusty, crushed rock. Every boot-scuff and rustle felt like a loud intrusion on the quiet morning.

I stretched my legs, laced my boots, and prepared my equipment. The plan was to meet Lloyd Athearn, Executive Director of the Colorado Fourteeners initiative, and hike up to the latest trail work site.

At the time: the trend of restrictions, timed entry, and permits was starting to spread. A few media outlets republished press releases from the Forest Service, but decisions like this don’t get made on a whim.

I wanted to know more. And the group that builds and maintains the trails, seemed like the best place to start asking questions. On the way to the build site, Lloyd and I passed a trail steward, posted by a creek crossing. The volunteer was stationed as part of a CFI program, encouraging hikers to follow “Leave no trace” principles. The thought process being: less damage delt is less damage that needs fixing.

The steward told me most hikers are so rushed, he usually only has time to blurt out: “Stay on the trail!”

A Data-Driven Solution

When Lloyd took over CFI some 14 years ago, he inherited some questionable book keeping on just how many hikers were on the trail. He was told a staggering half-a-million people were climbing each year.

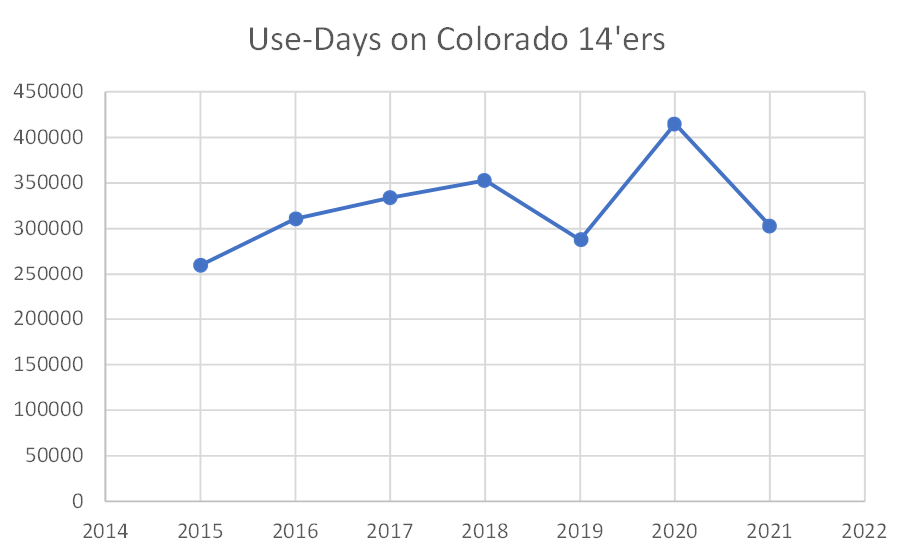

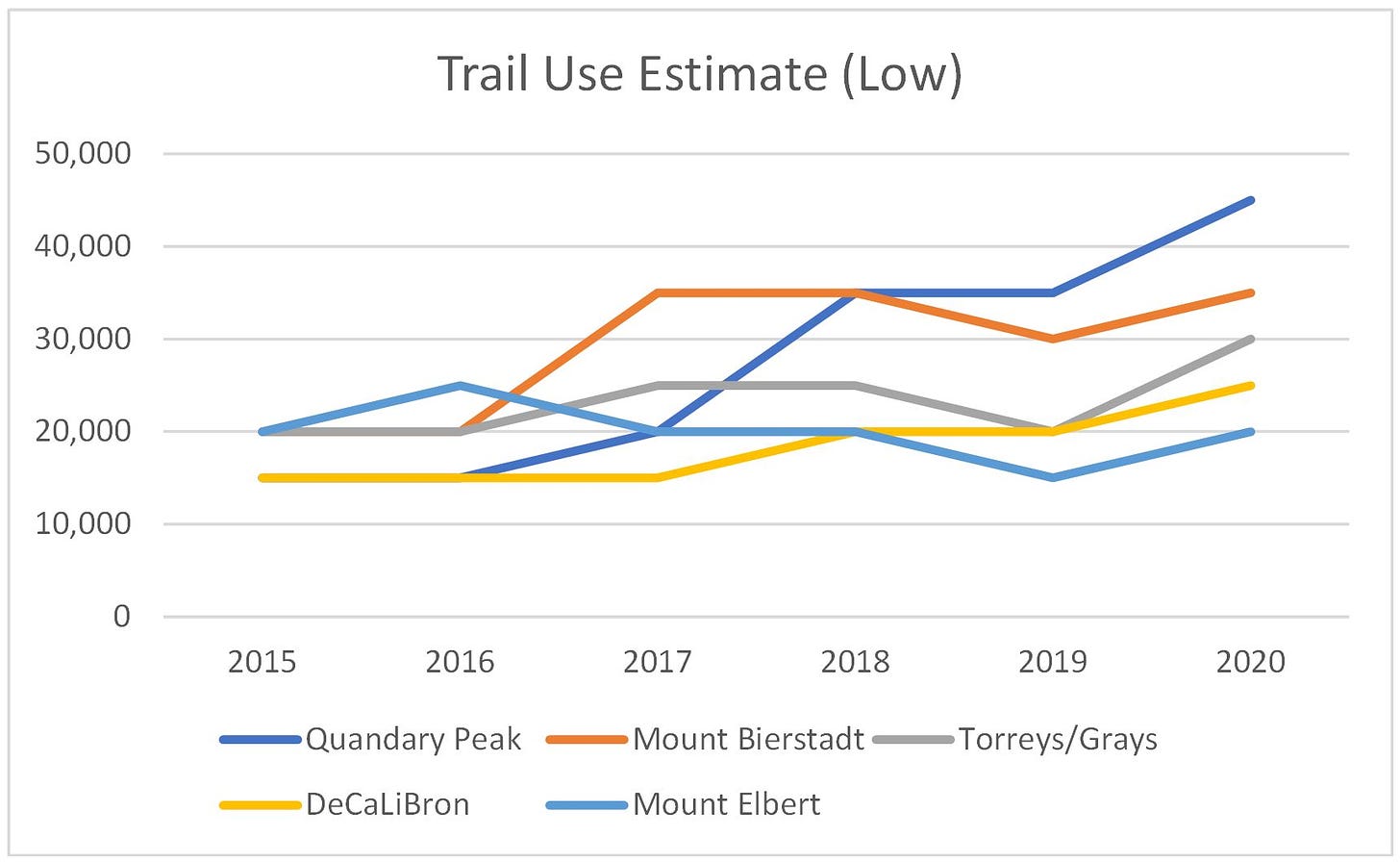

For quick context, we’ve never come close to those numbers, even during the pandemic boom:

“When I started pushing for: what was the methodology, how did they get it, you know, it seemed like it was put together with duct tape and balls of string, and things that didn't seem to really be terribly methodologically sound to me,” Lloyd said.

Determined to get a better count, Lloyd went out with a tally counter. He said he’d run into a few dozen people on a busy day, but needed better numbers.

CFI invested in tiny thermal counters to place alongside the trail, carefully hidden from view.

“Initially we weren't camouflaging them quite well enough. People would think there were geocaches,” Lloyd explained. He asked I not show you where the sensors are hidden, but did let me see one for myself.

The units are roughly the size of a cigarette case, and I promise you’re not going to find them.

After years of collecting data, mapping out actual trail routes, and carefully documenting conditions: Lloyd tells me he can now provide precise estimates of how much it will cost to repair or develop each of these trails.

“Very powerful from a fundraising perspective.”

Keep that one in mind, because I’ll be coming back to it.

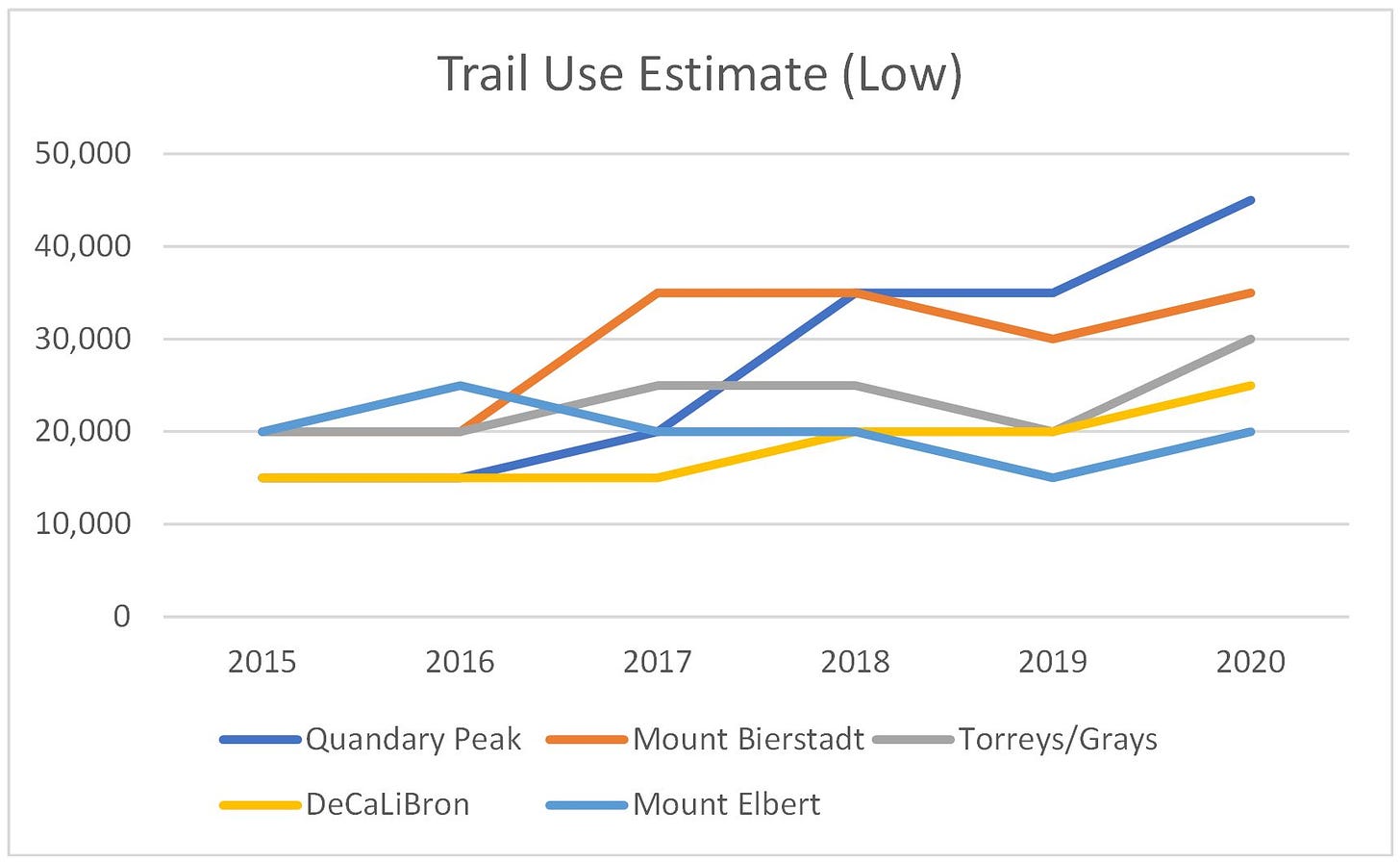

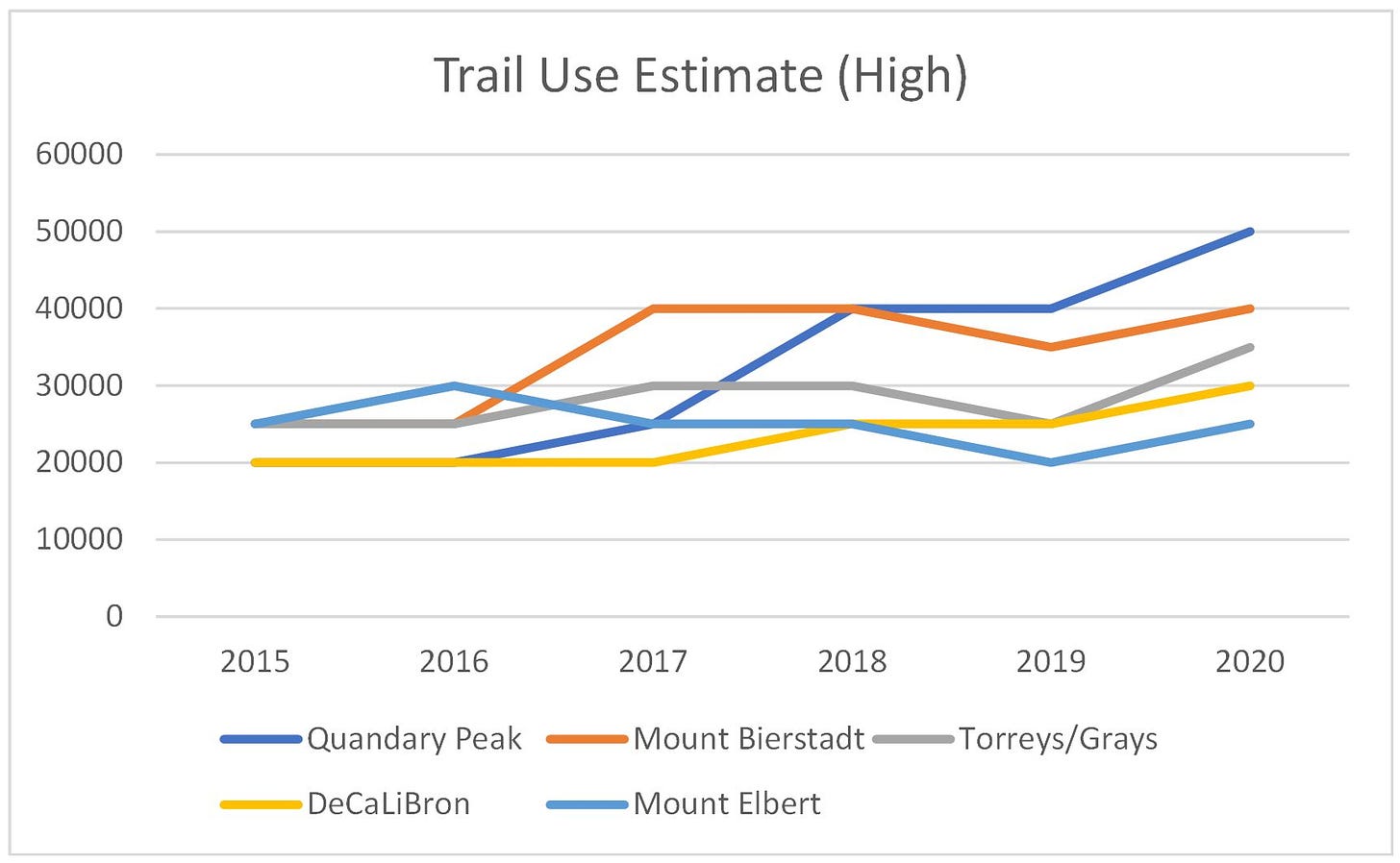

Below is the actual data-count from the Grays and Torreys. The peaks see tens of thousands of visitors each season, making the combined trail one of the most popular in Colorado.

Notice:1 Quandary does not become the most popular fourteener until it eclipses Bierstadt in 2019. The increased use in 2020 also closely follows the preceding growth trend.

If you’re out there on the trail, you already know how crowded things are. The surge in use isn’t new.

The pandemic may have played a role, but I’m not convinced it’s even the biggest problem. As it turns out, the raw number of hikers has very little to do with the state of the trail itself.

“You can get an awful lot of people on the trail and have very little impact to the surrounding ecosystem,” Lloyd explained. “In fact, a small number of people using you bad practices can cause far more damage.”

The more work has been done to reinforce trails, the more this impact is mitigated. Let’s peek at the data again.

Quandary saw an estimated 15,000-20,000 hiker use days in 2015. By 2020, that figure cracked 45,000-50,000.

Conventional wisdom dictates that the trail would be a mess. But the opposite happened. Quandary went from a “C” to an “A-” in CFI’s grading system, despite use more than doubling in the same time period.

Part of that is because before CFI started working on it, there was no Quandary Peak trail. Not officially, anyway. Of the state’s 53 fourteeners, only two were planned.

“The keyhole route on Long's Peak, and the bar trail on Pike's Peak. All of the other routes the people are using to climb the fourteeners were literally trampled into the tundra by climbers, usually taking as direct route as they could from trailhead to summit.”

Early hikers weren’t planning for the peak-bagging mania; cutting paths with no reinforcement or long-term strategy. Their primitive paths quickly degraded under the countless, untold footsteps that followed them.

Back on Grays and Torreys, the trail definitely needed some TLC. Condition slid from a “D-” in 2015, to an “F” by the end of 2019.

The lower part of the trail — built on the bones of an old mining road — isn’t the problem. Here; the route is obvious. Retaining walls, log steps, and thick shrubs make it perfectly clear where you’re supposed to walk.

But up higher, things are a bit less well-defined.

Unraveling Bad Hiking Habits

At the top of a small ridgeline, the trail unwinds and splits into multiple paths like a frayed rope, before merging back into a single route. You’ve probably seen this phenomenon, if not on a trail then alongside any paved path in a park, by a road, or even in a city. There are quite a few names for it: social trail, desire path, or goat track.

CFI calls them trail braids.

“Very clearly, this is the trail. Why are you going down there?” Lloyd pointed at one of the stray paths with a trekking pole. “Why are you cutting off here?

I’ve observed quite a few possible reasons during my trips. Most commonly:

Stepping around mud

Walking off the trail to pass other hikers2

Shortening the route by cutting off corners or switchbacks

Poor route-finding skills3

Small rocks line the sides of the path. But these appear to do little to dissuade bushwhacking.

In a city park, this behavior may lead to muddy conditions or necessitate re-seeding. In the tundra, the ecosystem is far more fragile.

When planning a new trail route, CFI will sometimes consult with botanists to minimize impact. On some trips, they find plants that have never been identified before. Others are so rare, they only exist in a handful of other clusters in the world.

“If you’re using the art example, you might be trashing a Van Gogh that is one-of-a-kind. Even the most common alpine tundra plants are uniquely adapted. These are in some ways the astronauts of the botanical world,” Lloyd said.

“They are living at the highest realms at which things will grow on our planet. They’re uniquely adapted to the strong ultra-violet light, the winds, the erratic precipitation. But their Achilles heel is they are vascular plants that are easily crushed by people walking on them.”

Upper Mountain Problems

These wildflowers are virtually the only vegetation to be found this close to the peak. Lower on the mountain, trail crews can use felled logs and larger boulders to control erosion.

As trail crew member Taylor Radigan explains, bringing in materials for trail construction becomes a big challenge. Beasts of burden — used to haul in materials on other projects — can’t easily traverse some of the narrow and rocky switchbacks.

Instead, they use gabions. These are hiked in as spools of wire mesh, shaped into cages, erected alongside the trail, and filled with smaller rocks. The resulting walls are effective for halting erosion and keeping people on the trail.

Many of these problems would not exist if everyone followed that quick snipped of advice from the trail steward: “Stay on the Trail!” Most of that advice is for your own protection, too.

In high territory surrounded by old mining claims like DeCaLiBron, haphazard paths could lead over weak tunnels or near open pits.

If you're taking the non-standard Kelso Ridge route up Grays and Torreys, a few miss-steps can quickly take you from a class 3 scramble, into class 4 or 5 territory.4

“We’re More Effective if we Work With Human Nature, Rather than Fight Human Nature.”

Lloyd expressed confidence that through continued work, the state’s most popular trails can handle the increased use.

But not every destination can, and some of these interested hikers will certainly seek a different challenge, rather than just staying home.

“Sometimes people say: ‘Oh my God there's so many people on the fourteeners. It’s chaos. We should limit them there, and then have them go to the thirteeners.’” Lloyd said. “We've got hundreds of thirteeners. You might be creating hundreds of millions of dollars in trail impact in other places.”

Or, put another way: the devil you know is better than the one you don’t.

Remember: one of the core strengths of CFI is that the group works in the realm of problems and solutions that are easy to see and measure. The organization has the ability to pinpoint specific segments of trails and show potential donors exactly what their dollars can accomplish.

Crowded trails also make for efficient spending on conservation. A trail upgrade on Quandary for example, mitigates the environmental impact of 40,000 hikers. If half of those hikers are forced to go elsewhere, that’s twice the work to temper the same amount of impact.

Some of the build crew members are volunteers. But CFI does employ paid staff. Crew member Taylor Radigan tells me this process involves living on the mountain for days at a time. Scattering hikers across the mountains also means spreading restoration efforts thin as well.

The Choke Point

Based on the data CFI gathers: if a hard limit on these popular peaks does exist, it’s not determined by the number of boots on the trail.

As long as hikers follow the “leave no trace” principles—

Plan ahead and prepare

Travel and camp on durable surfaces

Dispose of waste properly

Leave what you find

Minimize campfire impacts

Respect wildlife

Be considerate of other visitors

—and CFI carries on their work, the number of hikers walking on them is almost inconsequential in terms of impact. That is, unless there’s an emergency.

With tens of thousands of people frequenting the same spots, how do search and rescue teams keep up? Do bigger crowds mean tougher operations for these responders?

Part 2: “Fire, Aim, Ready!”

An overnight change at Grays and Torreys highlights the downstream challenges of crowd management.

Do You Remember the Chaos?

The first time I hiked Grays and Torreys, parking was an absolute cluster-hug. Once the tiny trailhead lot filled up, you kinda just squeezed your car wherever it fit. I remember pulling in behind a sedan that had bottomed out, and didn’t dare go farther.

If it had been light out when I left the car, and I saw where I’d left it, I would’ve spent the whole hike worrying whether it had rolled into the ravine.

All these cars parked along the road also made it a nightmare to drive back down to the highway. Then, one morning, signs like these lined the signs of the narrow roadway:

As previously outlined: this trail started as a bushwhack built on an old mining road. The parking area sits on a postage stamp of land, surrounded by homes on remote private property, with no room to expand.

Private landowners weren’t the only ones taking issue with the clogging of Steven’s Gulch.

As early as 2019, Alpine Rescue Team — which responds to calls at Grays and Torreys — raised concerns rescue vehicles may have difficulty getting through in case of emergency.

Steve and Dawn Wilson are both public information officers for the group. They echoed my earlier conclusion from CFI data: trail use is steadily climbing in line with Denver’s growing population.

Alpine Rescue Team is shouldered with a tricky burden. Their coverage area is along the I-70 corridor, and among the closest to the metro area. It’s tasked with responding to some of the most popular destinations in the state of Colorado.

“The fourteeners that we have are the beginning5 fourteeners. Evans and Bierstadt, and Grays and Torreys aren’t the ones that are the last ones people check off, when they’re doing the list. It’s the first ones,” Steve said.

Exactly which fourteeners see the most attention vary year to year.

These charts refer back to trail use estimates from CFI.6 In my previous analysis, I focused on over-all hiker numbers each year. Here, I use the same raw data, but change the presentation to examine how different destinations rise and fall in popularity.

Notice that while the overall use trends upward, different peaks jockey in the rankings.

Elbert falls from the top to bottom of the top five in terms of use over the last five years. Bierstadt’s use declines as more hikers flock to Quandary.

“It can be trendy too,” Dawn explained. “If something was in our local newspaper or local broadcast of a hike to do, then we’ll see an increase there as well as families or individuals explore that area.”

But if visibility pulls visitors in, increased restrictions push them away. As I’ve previously covered: if you can’t find a spot in the Grays and Torreys upper lot, you’ll have to drive back to the overflow area, right off the highway. This adds an extra 6 miles to the hike, making for a 13-mile total trip.

Part of the appeal of this trail always seems to have been the ability for hikers to bag two fourteeners over a relatively short distance. That mileage puts Grays and Torreys out of “beginner” territory.

While this could reduce foot traffic in the short term, Steve predicts this change won’t be permanent.

“I think that that impact will drift away. As it becomes less of something hikers are aware of, people will park up there again. It will become busy again. It’ll be our hotspot one of these years, coming up again. People are not finished climbing fourteeners because the road seems crowded.”

“How Many People are Having a bad day on Those Mountains?”

Foot traffic matters to CFI. Not so much for rescue crews.

“It’s not how many people are on these mountains; it’s just how many people are having a bad day on those mountains. We only see the people who get lost or get injured,” Dawn said.

In some cases, having more people on the trail actually reduces the need for a response. This slightly counter-intuitive phenomenon is sometimes referred to as a “Crowd Rescue.”

“If it’s really crowded one day, we might not get called for injuries because there’s so many people on that mountain, they just help each other out. We’ve actually had that happen a couple times, where we get called for a broken leg on the summit of mount Bierstadt. By the time we get there, the person’s already down because all the people on the mountain have helped out.” Dawn said.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but I’ve actually done a crowd rescue. It was during my first traverse of the famous Knife’s Edge, along Kelso ridge.

This phenomenon is not unique to Grays and Torreys — or even just the Alpine Rescue Team coverage area.

Anna DeBattiste is with Summit County Search and Rescue. This team handles calls a bit farther from the Denver Metro area. But they happen to cover the most popular peak in the state: Quandary.

Anna tells me they see plenty of crowd rescues, too.

“A lot of Times, There are so many People up There, They’ll just Crowd Rescue the Person and We don’t even Need to Go.”

If you’re in trouble, you should be hoping the trail is crowded. A lot of people have this idea that a helicopter will swoop in to save the day, the second you call for help.

Truth is, you’re usually hours away from responders reaching you.

“We’re not sitting in a fire station waiting for the call to go out. We’re home or at our day jobs. We have to respond from wherever we are in the county. Then we’ve got to hike into you,” Anna said.

Broadly speaking, the “casual hiker” types that tend to flock to these popular destinations, are actually easier to help — and this is another point that seems counterintuitive until you think about it for a second.

Inexperienced hikers usually don’t know enough to get themselves into real serious trouble; their lack of skill quite literally protects them from getting into higher-stakes situations.7

Lost? Someone from the closest rescue team can probably guide you back to the trail over the phone.

Tired? Sit down and rest for a little while.

Compound fractured your leg in an avalanche during your backcountry ski trip? Eh, you might need a bit more help.

Of those scenarios, guess which one Summit County Rescue gets the most.

“We get most injury calls and lost party calls on Quandary. The trends in recent years are more lost party calls in the winter,” Anna said. “In the summer, we get more hiker injuries. Occasionally we get a big burly rescue of someone who has gone off the backside and become cliffed out or injured in technical area. But more commonly it’s just someone injuring themselves on the front side.

Parking Restrictions and Rescue Calls

Like Grays and Torreys, times are a-changing on Quandary as well. The mountain now has both paid parking, and a paid shuttle system during peak summer months.

According to Anna: the change hasn’t made a difference in the number of rescue calls they get. But it is easier to bring in, and set up their emergency equipment.

While calls haven’t decreased on Quandary, Anna says they also haven’t gone up anywhere else either. So if crowding, restrictions, and reservations are changing hiker behavior, it’s not showing up in rescue trends. This could be for a few reasons.

Hikers could simply be undeterred and ignoring the restrictions. There’s certainly data-based evidence of this in the Park Quandary reservation system; the topic of the next installment in this investigation.

If hikers are seeking out replacement trails, they’re not running into trouble — at least not in large enough numbers to show up on rescue teams’ radar.

One trend that has cropped up and I would be remiss to leave it out: Alpine Rescue Team says they’re getting more rescue calls on weekdays, rather than weekends.

I chalk this up to more flexible schedules, brought on by the pandemic. It may seem trivial, but these search teams are made up of volunteers who have other jobs and responsibilities. This means rescue teams will need to be sure their lineup also includes hikers with a variety of schedule availability.

Steve assures me they have a deep lineup. But this may be something for other, less well-staffed teams to keep in mind.

Search for the Weakest Link

Rescue calls, like trail use, are on an upward trend. But the evidence doesn’t point to this being crowding-caused. As CFI Executive Director Lloyd Athearn points out, there is some degree of safety in numbers.

“Isn't it better all-around to get people on trails that are easy to follow? There is probably some level of safety in numbers if something happens here, rather than just having people willy-nilly going through un-trailed areas without the experience to do so,” Lloyd said.

I’d argue the increase in rescues actually comes from something else entirely: a lack of preparedness.

“Somewhere along the line climbing 14 years went from sort of an avocation of mountaineers and climbers, to a very mainstream bucket list type thing,” Lloyd said.

As the profile of the average visitor shifts from the older and more experienced mountaineers, motivations change too. Hikers have access to more guidebooks, maps, and trip-planning resources than ever. But not everyone uses them.

There’s an argument to be made that hikers looking to tick a peak off their bucket list, may be more likely to push through for the summit when they should turn around.

That’s when you can create problems for rescue crews.

"We also have missions because people try to get to the top to take that picture. Even if they have altitude sickness, or lightning coming.” Dawn said. “It’s not worth your injury or your life just to get the picture on the peak.”

Aside from setting yourself up for a miserable time, doing so can also incur a risk of injury for the rescue team looking for you.

Steve puts it best:

“The one thing that’s not going to change is the mountain. The mountain will be here tomorrow. It’ll be here next week. It’ll be here in a year. There’s plenty of time to not risk your life today, to get that picture in the fog, in the rain, and in the lightning. Come back tomorrow or next week, better prepared, better equipped, with more knowledge. And you get a better picture.”

The True Impact of Crowding

If you watched the film, and read my previous post, I’m sure you can see the pattern. Raw numbers are far less important than visitor behavior.

The limiting factor isn’t the number of hikers or rescue missions. I’d argue the most pressing problem is also the most mundane: parking.

On Quandary Peak, Summit County met this rather boring problem with an unusual solution: they turned the trailhead into a bona fide tourist attraction.

Part 3: The Quest to Save Quandary

Examining Colorado's most popular fourteener to figure out how to manage crowding on all the others.

You’re Gonna Need a Permit for that

The past two years have been marked by a series of falling dominoes: with new restrictions or capacity limits— and plans for future ones — being announced for many of Colorado’s most iconic destinations. I’ve been keeping a running tally, here:

As I outlined in the earlier installments, high numbers of hikers are a symptom of a larger conservation problem. This makes raw visitor numbers a bad metric to measure preservation progress.

Lloyd Athearn, Executive Director of the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative, warned that focusing too much attention here could put outdoor access out of reach for a lot of people:

“If we start focusing on: ‘Close the gate there too many people out here,’ then that either causes people to go to other places that are ungated, which might cause a lot of the environmental impact, or it's all of these different cost and hassle barriers. If you're if you're thinking of some of these things, even if they're not high fees but you have to plan in advance and you have to schedule your reservation, I can tell you that's probably going to be more easily accomplished by a middle class or wealthier person with an office job.”

Quandary, a new Culebra

When I first started work on this project, Quandary struck me as an interesting case study because it seemed Summit County was trying to strike a balanced approach. Originally: they rolled out a parking reservation system with a free shuttle.

“What a neat little way to balance access against overcrowding,” I thought. Then they required paid reservations to use the shuttle, too.

So effectively, there’s no longer any way — aside from having someone drop you off — to hike Quandary during the popular summer summit season without planning and paying.

I’ve called attention to this in previous reporting on this, but I feel the need to repeat it here: several local governments help kick money over to CFI to fund trail restoration and upgrades. Summit County does not — through reservation fees, or otherwise.

In my view, what is happening to this mountain represents something we haven’t really seen since the Pikes Peak Cog Railway reached the summit: the development of alpine environments as full-blown tourist attractions.

Is this actually a viable strategy for conservation? How would this impact the outdoor experience? I’ve got answers.

The Absolute Mess that was the McCullough Gulch Parking Situation

Much like the situation over at Grays and Torreys; Quandary Peak’s popularity has long since outgrown its meager parking lot. Before the pilot program began, hikers parked any place their car could fit.

At the height of the 2021 season, cars filled the lot, lined McCullough Gulch Road, then started lining up along the nearby Blue Lakes Road. On some days, parked vehicles threatened to spill over onto the nearby state highway.

Summit County knew this was a problem. They’d been trying to hammer out a solution. But before they could properly flesh out a proposal, then-Assistant County Manager Bentley Henderson8 tells me safety concerns pushed them to act immediately.

“The intent was for the plan to be more fully complete and adopted before we took any action but that just wasn't an alternative, based on the urgency that was given us by the board,” Henderson explained.

One of the final straws: the parking overflow was so bad, an emergency vehicle couldn’t get through.

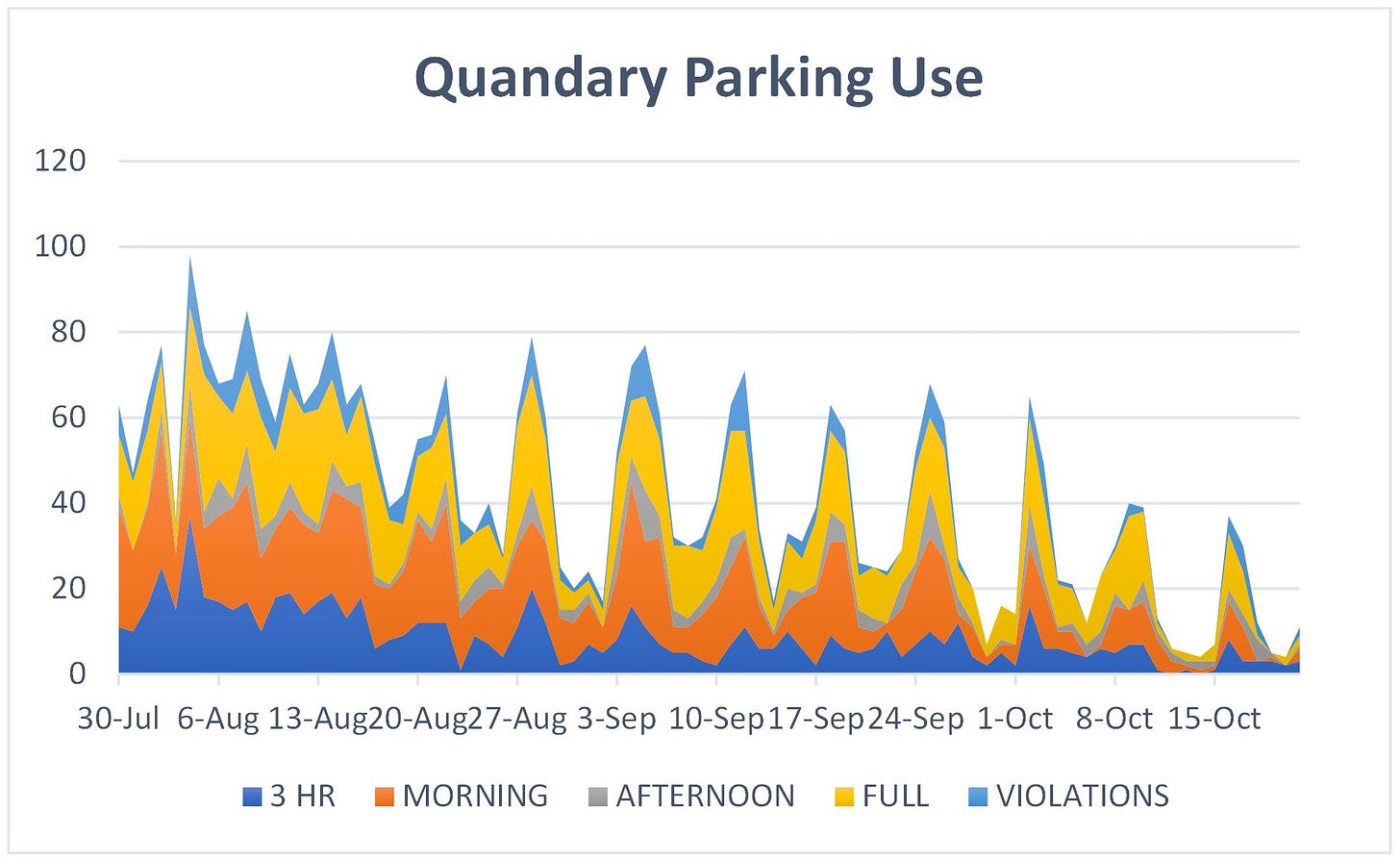

The county pulled the trigger on their parking shuttle program at the end of July, 2021. After a bit of advance warning to visitors, the first week of the shuttle looked like this:

Data for all graphs in this article is compiled from a variety of sources: shuttle use records from Summit Express, parking reservation records provided by the now former Assistant County Manager, and carpooling estimates from the Quandary Peak survey data.

From the word go: visitors were quick to adopt the then-free shuttle program; choosing it9 over the parking reservations by a wide margin.

I don’t have a daily tally from shuttle use. But according to Summit County Express owner Bob Roppel, the shuttle moved more than 12,000 people from the airport lot to the trailhead, throughout the 2021 season.

Based on the parking reservation data, we can place the estimated number of parked hikers at 8,938.10 Click the foot note if you're interested in seeing how I worked these numbers out. For those of you who detest math as much as I do, I turned all the data into this colorful graph:

The chart shows a pretty clear weekly cycle of visitors, peaking Saturdays and bottoming out midweek. But the valleys in the data points are much more shallow in August.

In normal-human-speak: that means trail use was actually pretty evenly spread out throughout the week during the summer. I’d chalk that up to the reservation system forcing hikers to spread out their trips.

You may remember: Steve Wilson of Alpine Rescue Team pointed out that with more restrictions on popular peaks, they’ve started getting more weekday rescue calls. Alpine Rescue doesn’t cover Quandary though, so I can’t extrapolate too much.

This chart just seems to show a similar trend on other mountains.

Having Reservations

The overwhelming majority of parked hikers did make reservations, favoring either full day or morning-only time slots.

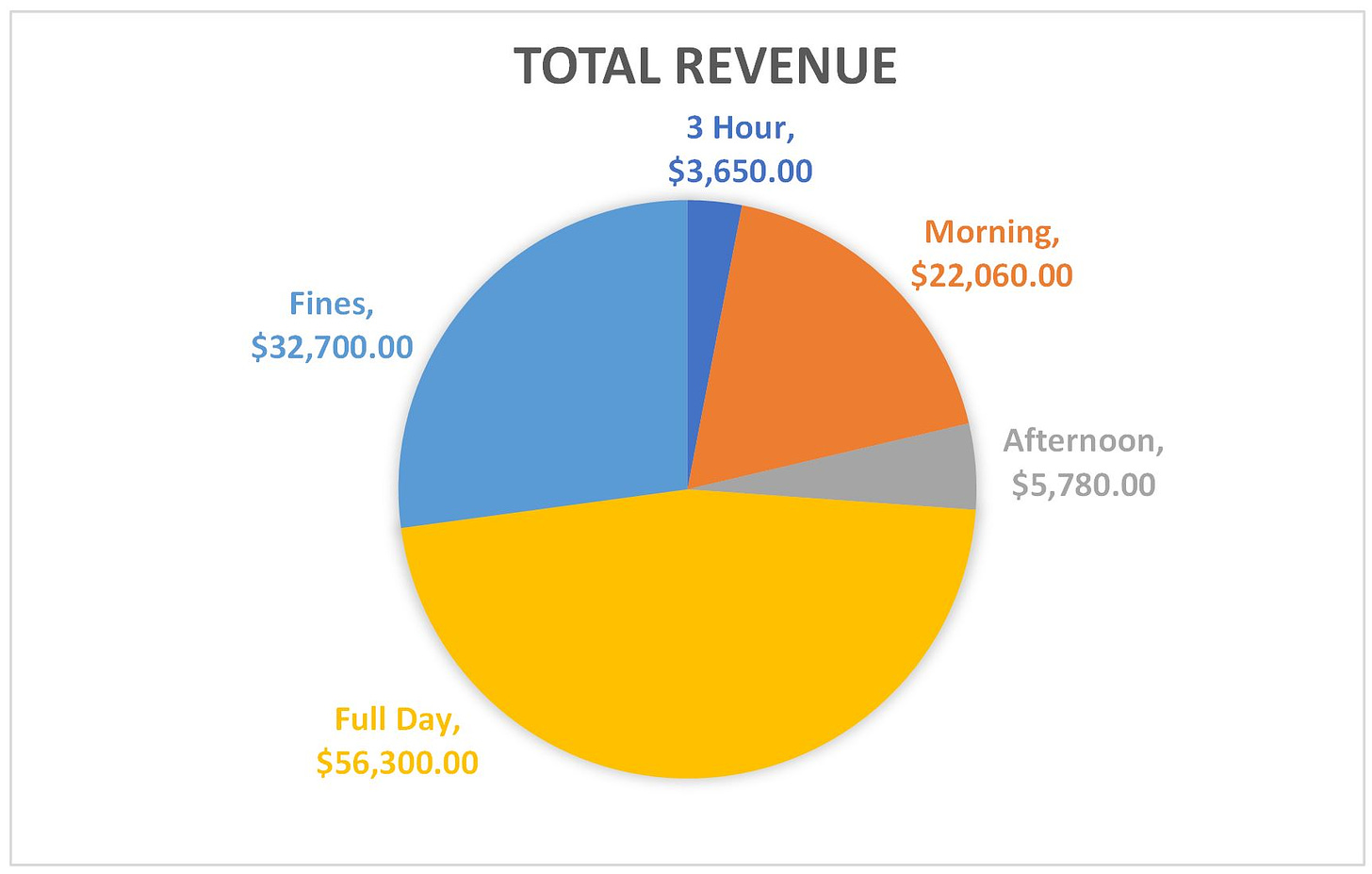

Summit County didn’t say how much money the permit system took in. But we can figure it out using the information we have.

The number of people who made each different kind of reservation

Exactly how much the different reservations cost

With a bit more math, we get a grand revenue total of $120,49011 from the pilot program, with more than a quarter coming from fines.

The system has been streamlined a bit since 2021. Now, there are no morning/afternoon options. This will no doubt corral more visitors into buying full-day passes, which made up the lion’s share of the system revenue:

What Next?

The shuttle program’s goal was to alleviate safety concerns by unclogging the road to the trailhead. Objectively, it achieved this goal, removing an estimated 57% of vehicles over the duration of the pilot program.

But that comes at the cost of convenience to some neighbors who may want fee-free access to local trailheads, as well as the tangible fiscal cost to run the shuttle.

As far as I’m aware, Summit County has not stated publicly how much it’s spending on this program. While the reservations contribute, we do know they’re not enough to pick up the full tab.

“It contributes to the shuttle system it doesn't fully pay for it.” Mr. Henderson said. “Our estimate is that the shuttle is going to be well into the six figures.”

I actually came to an estimate on how much this program costs to run, using algebra and a few other scraps of information I have. But it felt too speculative, and I felt the actual price tag is almost inconsequential for reasons I’ll get to in a minute.

This brings us to a bit of a crossroads in the Quandary Peak example. The peak management plan featured several other scenarios for expanding parking — even adding lanes alongside the road — but even their scenario that adds the greatest amount of parking spaces would already be strained by existing visitor numbers. 12

Going down this road would likely bring us to the exact same discussion in another season or two.

I contemplated several other potential solutions here, but they amount to little more than navel-gazing. Summit County seems committed to the shuttle program, with possible expansion that could help lower the effective cost.

The Alpine Amusement Park

There are a lot of popular trails in Summit County, especially near Breckenridge; a fact local leadership is acutely aware of. As tourism increases, the shuttle could become the bones of a bigger infrastructure network that links a number of popular hiking spots to the downtown area.

“Other trailheads will be looked at so that the shuttle becomes more of a more comprehensive trail access program than just Quandary,” Mr. Henderson said.

The Gold Hill and Dredge trails were brought up as potential candidates.

This expansion could usher in a kind of alpine amusement park-style outdoor recreation on toughened-up, high-capacity trails, with Breckenridge at the core.

A study conducted by Doctors Loomis and Keske in 2008, examined exactly how much money visitors spend within 25 miles of the peak they plan to climb. In a previous article, I came up with what I consider to be a reasonable, inflation adjusted number of $113.29 per hiker. If the visitor is staying in a hotel or short-term rental, that number goes up to $358.61.

With the number of visitors we see on these peaks, Quandary is a multi-million dollar tourist attraction, all by itself.

Statewide, CFI estimates the economic impact of fourteener climbing to be in the neighborhood of $112.5 million.

Remember earlier when I said the shuttle program’s cost was inconsequential? Even my highest estimate is a full order of magnitude cheaper than the tourism that’s generated by Quandary Peak.

The money and interest are both present. Would it be possible to monetize the mountains, and use the revenue to help conserve them? How would this play out on other mountains? And how will this reshape the outdoor experience moving forward?

Part 4: Tickets, Please

Could treating Colorado's most popular peaks like theme park rides actually save them from destruction and overuse?

Summit County has struck a middle-ground in its quest to save Quandary Peak from overuse: paid parking reservations for those who want the convenience, and a free shuttle to ensure access isn’t hindered.

Meantime, the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative has worked diligently to ensure the trail is robust, hardened, and capable of carrying the tens of thousands of visitors to the top.

Both parties seem confident if there is a hard capacity limit to what Quandary can handle under these conditions, we haven’t found it yet.

The only expense to these solutions — aside from the spillover shuttle operation cost picked up by the Summit County taxpayer — seems to be a lost sense of remote wonder.

Alpine Rescue Team member Dawn Wilson puts it better than I could:

“That’s the unfortunate part of Colorado: it’s becoming kind of like an amusement park.”

In the previous installment, I suggested Breckenridge could be poised to become the nucleolus for a new sort of tourist attraction: a burgeoning alpine amusement park with the infrastructure to conveniently bring large numbers of visitors to a network of popular trails — no driving required.

It’s up to the residents of Summit County, and Breckenridge if they want to go down this path. But this begs a bigger question:

Is this solution even viable, or even desirable for the state’s other popular peaks?

Bierstadt

Let’s try to apply this solution to the next most popular peak on our list: Mount Bierstadt. The closest logical place to run the shuttle would be Georgetown, some 25 minutes away from the trailhead, and at the bottom of Guanella Pass.

The pass also effectively begins in the middle of a neighborhood street, meaning these homeowners would have to decide between having a bus station at their doorstep, or scores of cars passing through to reach the pass.

Bierstadt will likely face issues down the road, but there’s considerably more space at the trailhead for a solution to be implemented. It would probably make more sense fore stakeholders to focus their efforts up there, rather than down in Georgetown.

Grays and Torreys

By my estimate, this situation will be the most difficult to solve. The trailhead is at the end of Steven’s Gulch, a narrow, winding road lined with private homes. Expanding the upper lot is likely not feasible due to private property claims.

A shuttle system could, in theory, run from the lower lot to the upper. But finding a shuttle vehicle capable of reliably driving over the rocky terrain would likely be prohibitively expensive.

I predict Grays and Torreys will naturally fall out of peak popularity due to the Steven’s Gulch parking restrictions, though it’s still unclear where those hikers will be diverted.

DeCaLiBron

Any member of the mountaineering community likely knows these peaks are already caught in a precarious struggle for access.

The nearby town of Alma already charges for parking, so requiring paid reservations in advance instead isn’t much of a stretch. But due to the trail’s delicate situation: further infrastructure development here could pose problems.

If you didn’t know: the entire summit of Mount Bross, as well as several segments of the trail, cross private property. Due to the area’s old mining claims: wandering off route poses a higher-than-usual safety risk.

Liability concerns for the landowners have been inflamed by a recent ruling: James Nelson and Elizabeth Varney v United States of America. The short version is that Nelson went for a bike ride on an unofficial trail that crossed Airforce Academy property in Colorado Springs. Though it wasn’t on the map, it was commonly used, and the Academy knew the trail was there; they even erected signage for it.

Nelson hit a sink hole on the path and was badly hurt. After years of litigation, he was awarded several million dollars by the courts.

It’s possible infrastructure such as expanded parking, permitting systems, or shuttles, will pose a concern for landowners. Would these services give visitors a greater expectation of safety on the trail, and could these expectations lead to increased liability risk?

I see developments around this trailhead as something that could bog down talks between the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative, and the owners about preserving access.

Elbert

Of all the popular trails, I’m most inclined to argue this one can be left alone. Bringing back our trail use graphs once again: Mount Elbert has actually decreased in popularity since the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative deployed hiker counting devices.

Elbert is also the farthest of these top peaks from Denver, the greatest distance from I-70,13 and features the longest trail, upwards of ten miles.

In short, Elbert lacks the pull-factors we’ve been discussing that led to Quandary’s snowball growth during the last five years.

Doomed From the Beginning

There is no panacea for degradation and crowding. What works on one peak will not necessarily translate to the others.

Colorado now has to reckon with an unfortunate truth: these trails were doomed to their current fate from the day they were beaten into the tundra. Use has expanded lightyears beyond anything the first hikers to summit could have possibly foreseen.

It’s left present-day policymakers with big problems, and not enough space to solve them. That’s why we need to be thinking long-term.

The true solution to trail crowding is a three-pronged approach that must occur at the macro level, or we will be merely pushing the problem from peak to peak.

The creation of new, well-planned open spaces

The fortification of existing spaces to handle increased use

The adoption of good trail etiquette to reduce impact

These solutions will require cooperation between state government, conservation organizations, and visitors themselves.

Future Proofing

This one is a job for Colorado state government. As the state grows, there will invariably be a need for more open spaces for recreation. These new spaces will need to be designed with room to grow. Here, laying out spaces with the model we’re seeing at Quandary may be a good starting off point. That may mean:

Parking lots away from private property and utility access

Robust roads that can easily accommodate emergency vehicles and shuttles

Designated parking lanes along the road itself

Access for public transportation

Reinforcement

The Colorado Fourteeners Initiative is already hard at work on this point: hardening up the infrastructure at popular trails, rather than trying to encourage hikers to move elsewhere. Lloyd Athearn, Executive Director of the CFI, argues that predicting human behavior is a fool’s errand.

“Shouldn't we try to meet the people where they are? And you know, if they want to climb fourteeners, let's improve the fourteener trail so that they can be more robust,” he argued.

And that’s effectively what the CFI is doing for the popular peaks. This means that provided we exercise good habits, these trails will not hit any kind of high-capacity limit.

This brings me to our next solution:

Reducing our Impact

While the CFI works to increase the amount of impact a trail can handle, hikers can also work to reduce the amount of impact they produce.

I made these points back in the beginning of this series:

Less about how many boots are on the trail, and more about how many leave it

Not how many people need help, but the severity of the situations they get into

Less about the raw number of visitors, and more about how they get there

Summit County’s visitor management plan acknowledges this too. Take a look at this excerpt from the report:

“The Quandary Peak trail has had improvements and appears to be successfully supporting the existing visitor capacity. However, this trail has seen conflicts between off leash dogs and wildlife. Human and dog waste, as well as illegal camping and campfires, additionally impact the water quality and infrastructure of Blue Lakes, an important water source for the Front Range. These issues have negative impacts on wildlife habitat, environmental quality, visitor experiences, and public safety.”

CFI has also branched out into this area by posting trail stewards near popular routes to encourage visitors to follow Leave No Trace principles.

These are all things every hiker can do to reduce impact on the trails, wildlife, and infrastructure that help keep our outdoor spaces accessible:

Avoid pulling off the road to park

Stick to the trail

Pack out all garbage and waste

Follow area camping and campfire rules

Leash pets to prevent wildlife conflict

Prepare, and pack smart to avoid over-burdening rescue groups

Be a good steward of the outdoors

This last point is probably the trickiest. I’ve discussed this with Eddie Taylor, of Full Circle Everest: trying to gatekeep the outdoor community often backfires. It’s by welcoming and mentoring newcomers that we increase reverence and care for these wild spaces.

That interview, by the way, is available here:

Fixing the problem would be so much easier if it just involved paving a massive parking lot, with sidewalks stretching from trailhead to peak. But aside from being unfeasible and largely unnecessary, it would take away what makes our experiences special.

The Single Most Important Change Needs to be in the Mindset of the Outdoor Community.

As Lloyd pointed out during our discussion: “Somewhere along the line climbing 14 years went from sort of in avocation of mountaineers and climbers to a very mainstream bucket list type thing.”

To save our open spaces: we must return to experiential, rather than list climbing.

As I’ve laid out throughout this series: those focused only on summiting are apt to press on past their ability level, impending exhaustion, and into risky conditions.

Meanwhile: the profile of the hikers is shifting from experienced mountaineers, toward younger, less experienced visitors with a taste for adventure and inclination toward spontaneity.

Make no mistake: newer hikers aren’t at fault for trail crowding and degradation. Conservation principles and preparedness are not innate, but ideas taught and learned through a healthy community.

The best thing we can do is pass on our love and reverence for the outdoors, and the idea that every step is special — not just the final one we plant on the summit.

Thank You for Reading

This journey has been a long one. The interviews included were conducted over many months on whatever time I could spare away from my day job. If it’s something you enjoyed, found informative, or want to see more: click the subscribe button below.

It’s free and helps support investigations like this one.

Data methodology: these graphs are compiled from the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative annual use reports, which date back to 2015. 2021 Data is not yet available.

A phenomenon I’ve observed since the start of the pandemic: social distancing worsens social trails. I’ve watched other hikers stray far from the path to avoid coming within six feet of one another.

I’ve been guilty of this in the past. But the environmental impact of crossing a boulder field is significantly less than that of trampling alpine flora.

This mostly applies to the Kelso Ridge route, where the trail is much harder to follow. While the main trail does have some steep cliffs, CFI has worked hard to ensure the route is clear and stable.

Notice: Steve says beginning, not beginner. There’s a difference. He clarifies later in the interview that while difficulty is certainly relative, there is no such thing as a beginner fourteener. All should be approached with caution, respect, and preparedness.

Data methodology: these graphs are compiled from the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative annual use reports, which date back to 2015. 2021 Data is not yet available.

My mountaineering friend describes this phenomenon using the expression, “The more you know, the deeper you go.”

Henderson resigned from his role before this report’s release

I don’t have enough information to determine whether hikers made this decision based on preference, or another confounding factor. Reservations could’ve been full, or they could’ve forgotten to make one, and returned to the parking lot instead.

From the data Summit County shared with me, I know they logged a combined total of 3,575 cars that either made reservations, or were ticketed.

Before launching the program, Summit County also did surveys to figure out how many hikers travel in cars together. They arrived at an average of 2.5 hikers per vehicle.

3,575 x 2.5 = 8,937.5

You can’t have a partial person on the trail, so we need to round up to the next whole number: 8,938. Ta-da!

The original pilot program let you make absurdly short half-day parking reservations. It’s possible some hikers made a reservation, came back too late, and also got a ticket.

This is not an exact figure provided by Summit County, rather, it was extrapolated by multiplying parking data with pricing information

Parking Scenario B from the Visitor Use Management Framework report created a hypothetical visitor capacity of 637.5 per day. Visitor use surpassed this threshold during the first week of the pilot program.

I’m aware other fourteener routes are longer. For the purposes of this discussion, I’m only referring to our list of 5 most popular trails.