The Devil We Know — The Alpine Amusement Park Part Unraveled, Part 1

Is it better to keep the problem concentrated where you can see it? This written investigation delves deeper into the issues highlighted in the documentary, "The Alpine Amusement Park."

*This post was supposed to be sent at 8:00 a.m. this morning. Due to an error, it is being sent now. My apologies for the delay.

If you haven’t watched “The Alpine Amusement Park,” It’s available now, here!

Stay on the Trail!

Despite my best effort to secure my camera gear in the trunk, the bumpy ride up Steven’s Gulch managed to shake it loose. The tripod, my backpack, and I all jostled around in my jeep, bouncing over rocks and boulders.

After white-knuckling the steering wheel past a few steep drop-offs to the water below, I pulled into the tiny parking area. A car stood in almost every space, but I didn’t see another soul hanging around.

I parked near the ruins of an old mining claim, and stepped out onto dusty, crushed rock. Every boot-scuff and rustle felt like a loud intrusion on the quiet morning.

I stretched my legs, laced my boots, and prepared my equipment. The plan was to meet Lloyd Athearn, Executive Director of the Colorado Fourteeners initiative, and hike up to the latest trail work site.

At the time: the trend of restrictions, timed entry, and permits was starting to spread. A few media outlets republished press releases from the Forest Service, but decisions like this don’t get made on a whim.

I wanted to know more. And the group that builds and maintains the trails, seemed like the best place to start asking questions. On the way to the build site, Lloyd and I passed a trail steward, posted by a creek crossing. The volunteer was stationed as part of a CFI program, encouraging hikers to follow “Leave no trace”1 principles. The thought process being: less damage delt is less damage that needs fixing.

The steward told me most hikers are so rushed, he usually only has time to blurt out: “Stay on the trail!”

A Data-Driven Solution

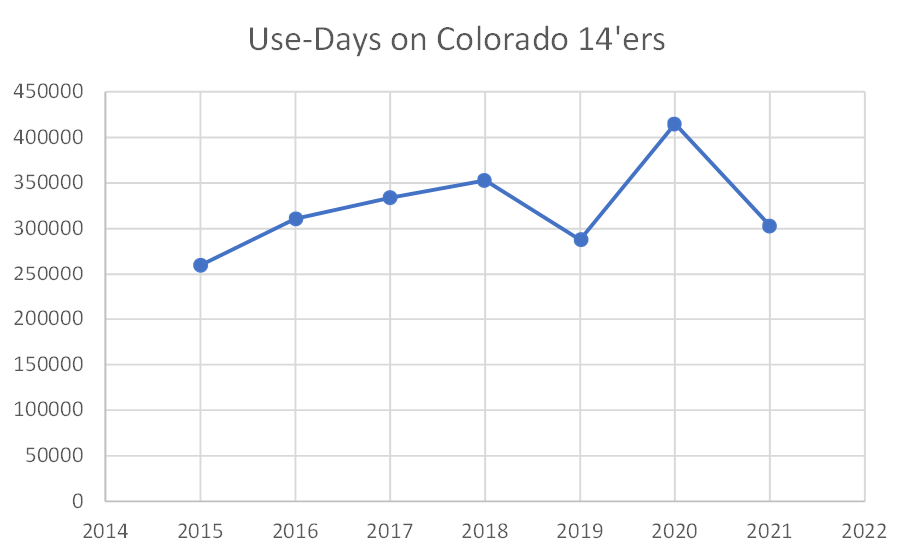

When Lloyd took over CFI some 14 years ago, he inherited some questionable book keeping on just how many hikers were on the trail. He was told a staggering half-a-million people were climbing each year.

For quick context, we’ve never come close to those numbers, even during the pandemic boom:

“When I started pushing for: what was the methodology, how did they get it, you know, it seemed like it was put together with duct tape and balls of string, and things that didn't seem to really be terribly methodologically sound to me,” Lloyd said.

Determined to get a better count, Lloyd went out with a tally counter. He said he’d run into a few dozen people on a busy day, but needed better numbers.

CFI invested in tiny thermal counters to place alongside the trail, carefully hidden from view.

“Initially we weren't camouflaging them quite well enough. People would think there were geocaches,” Lloyd explained. He asked I not show you where the sensors are hidden, but did let me see one for myself.

The units are roughly the size of a cigarette case, and I promise you’re not going to find them.

After years of collecting data, mapping out actual trail routes, and carefully documenting conditions: Lloyd tells me he can now provide precise estimates of how much it will cost to repair or develop each of these trails.

“Very powerful from a fundraising perspective.”

Keep that one in mind, because I’ll be coming back to it.

Below is the actual data-count from the Grays and Torreys. The peaks see tens of thousands of visitors each season, making the combined trail one of the most popular in Colorado.

2Notice: Quandary does not become the most popular fourteener until it eclipses Bierstadt in 2019. The increased use in 2020 also closely follows the preceding growth trend.

If you’re out there on the trail, you already know how crowded things are. The surge in use isn’t new.

The pandemic may have played a role, but I’m not convinced it’s even the biggest problem. As it turns out, the raw number of hikers has very little to do with the state of the trail itself.

“You can get an awful lot of people on the trail and have very little impact to the surrounding ecosystem in,” Lloyd explained. “In fact, a small number of people using you bad practices can cause far more damage.”

The more work has been done to reinforce trails, the more this impact is mitigated. Let’s peek at the data again.

Quandary saw an estimated 15,000-20,000 hiker use days in 2015. By 2020, that figure cracked 45,000-50,000.

Conventional wisdom dictates that the trail would be a mess. But the opposite happened. Quandary went from a “C” to an “A-” in CFI’s grading system, despite use more than doubling in the same time period.

Part of that is because before CFI started working on it, there was no Quandary Peak trail. Not officially, anyway. Of the state’s 53 fourteeners, only two were planned.

“The keyhole route on Long's Peak, and the bar trail on Pike's Peak. All of the other routes the people are using to climb the fourteeners were literally trampled into the tundra by climbers, usually taking as direct route as they could from trailhead to summit.”

Early hikers weren’t planning for the peak-bagging mania; cutting paths with no reinforcement or long-term strategy. Their primitive paths quickly degraded under the countless, untold footsteps that followed them.

Back on Grays and Torreys, the trail definitely needed some TLC. Condition slid from a “D-” in 2015, to an “F” by the end of 2019.

The lower part of the trail — built on the bones of an old mining road — isn’t the problem. Here; the route is obvious. Retaining walls, log steps, and thick shrubs make it perfectly clear where you’re supposed to walk.

But up higher, things are a bit less well-defined.

Unraveling Bad Hiking Habits

At the top of a small ridgeline, the trail unwinds and splits into multiple paths like a frayed rope, before merging back into a single route. You’ve probably seen this phenomenon, if not on a trail then alongside any paved path in a park, by a road, or even in a city. There are quite a few names for it: social trail, desire path, or goat track.

CFI calls them trail braids.

“Very clearly, this is the trail. Why are you going down there?” Lloyd pointed at one of the stray paths with a trekking pole. “Why are you cutting off here?

I’ve observed quite a few possible reasons during my trips. Most commonly:

Stepping around mud

Walking off the trail to pass other hikers3

Shortening the route by cutting off corners or switchbacks

Poor route-finding skills4

Small rocks line the sides of the path. But these appear to do little to dissuade bushwhacking.

In a city park, this behavior may lead to muddy conditions or necessitate re-seeding. In the tundra, the ecosystem is far more fragile.

When planning a new trail route, CFI will sometimes consult with botanists to minimize impact. On some trips, they find plants that have never been identified before. Others are so rare, they only exist in a handful of other clusters in the world.

“If you’re using the art example, you might be trashing a Van Gogh that is one-of-a-kind. Even the most common alpine tundra plants are uniquely adapted. These are in some ways the astronauts of the botanical world,” Lloyd said.

“They are living at the highest realms at which things will grow on our planet. They’re uniquely adapted to the strong ultra-violet light, the winds, the erratic precipitation. But their Achilles heel is they are vascular plants that are easily crushed by people walking on them.”

Upper Mountain Problems

These wildflowers are virtually the only vegetation to be found this close to the peak. Lower on the mountain, trail crews can use felled logs and larger boulders to control erosion.

As trail crew member Taylor Radigan explains, bringing in materials for trail construction becomes a big challenge. Beasts of burden — used to haul in materials on other projects — can’t easily traverse some of the narrow and rocky switchbacks.

Instead, they use gabions. These are hiked in as spools of wire mesh, shaped into cages, erected alongside the trail, and filled with smaller rocks. The resulting walls are effective for halting erosion and keeping people on the trail.

Many of these problems would not exist if everyone followed that quick snipped of advice from the trail steward: “Stay on the Trail!” Most of that advice is for your own protection, too.

In high territory surrounded by old mining claims like DeCaLiBron, haphazard paths could lead over weak tunnels or near open pits.

If you're taking the non-standard Kelso Ridge route up Grays and Torreys, a few miss-steps can quickly take you from a class 3 scramble, into class 4 or 5 territory.5

“We’re More Effective if we Work With Human Nature, Rather than Fight Human Nature.”

Lloyd expressed confidence that through continued work, the state’s most popular trails can handle the increased use.

But not every destination can, and some of these interested hikers will certainly seek a different challenge, rather than just staying home.

“Sometimes people say: ‘Oh my God there's so many people on the fourteeners. It’s chaos. We should limit them there, and then have them go to the thirteeners.’” Lloyd said. “We've got hundreds of thirteeners. You might be creating hundreds of millions of dollars in trail impact in other places.”

Or, put another way: the devil you know is better than the one you don’t.

Remember: one of the core strengths of CFI is that the group works in the realm of problems and solutions that are easy to see and measure. The organization has the ability to pinpoint specific segments of trails and show potential donors exactly what their dollars can accomplish.

Crowded trails also make for efficient spending on conservation. A trail upgrade on Quandary for example, mitigates the environmental impact of 40,000 hikers. If half of those hikers are forced to go elsewhere, that’s twice the work to temper the same amount of impact.

Some of the build crew members are volunteers. But CFI does employ paid staff. Crew member Taylor Radigan tells me this process involves living on the mountain for days at a time. Scattering hikers across the mountains also means spreading restoration efforts thin as well.

The Choke Point

Based on the data CFI gathers: if a hard limit on these popular peaks does exist, it’s not determined by the number of boots on the trail.

As long as hikers follow the “leave no trace” principles—

Plan ahead and prepare

Travel and camp on durable surfaces

Dispose of waste properly

Leave what you find

Minimize campfire impacts

Respect wildlife

Be considerate of other visitors

—and CFI carries on their work, the number of hikers walking on them is almost inconsequential in terms of impact. That is, unless there’s an emergency.

With tens of thousands of people frequenting the same spots, how do search and rescue teams keep up? Do bigger crowds mean tougher operations for these responders?

In Part 2:

We hear from two search and rescue teams, responsible for covering the most hectic destinations in Colorado. You’ll hear the unexpected impact these long lines of hikers are bringing to rescue operations.

A set of guidelines in the outdoors, centered around reducing your impact on the outdoor environment to near-zero during your adventure. My grandfather summed it up with the adage: “Take only pictures and leave only footprints.” You can read about these principles in depth, here.

Data methodology: these graphs are compiled from the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative annual use reports, which date back to 2015. 2021 Data is not yet available.

A phenomenon I’ve observed since the start of the pandemic: social distancing worsens social trails. I’ve watched other hikers stray far from the path to avoid coming within six feet of one another.

I’ve been guilty of this in the past. But the environmental impact of crossing a boulder field is significantly less than that of trampling alpine flora.

This mostly applies to the Kelso Ridge route, where the trail is much harder to follow. While the main trail does have some steep cliffs, CFI has worked hard to ensure the route is clear and stable.

So interesting! Thanks, Cole.