The Quest to Save Quandary — The Alpine Amusement Park Unraveled, Part 3

Examining Colorado's most popular fourteener to figure out how to manage crowding on all the others.

This written investigation delves deeper into the issues highlighted in the documentary, "The Alpine Amusement Park." The previous installments in the series are below:

And here’s a quick refresher from parts 1 & 2:

Trail use has been increasing steadily for a long time

Popular trails are being fortified against degradation

Small numbers of visitors violating “Leave no Trace” principles have a higher environmental impact than large numbers of visitors who do follow the principles

The “Crowd Rescuing” phenomenon helps hikers who are lost or suffering from minor injuries on crowded trails

The peak-bagging mindset may make visitors more likely to take unnecessary risks

Almost all fourteeners were unplanned, setting them up for logistical nightmares as popularity grew

The past two years have been marked by a series of falling dominoes: with new restrictions or capacity limits— and plans for future ones — being announced for many of Colorado’s most iconic destinations. I’ve been keeping a running tally, here:

As I outlined in the earlier installments, high numbers of hikers are a symptom of a larger conservation problem. This makes raw visitor numbers a bad metric to measure preservation progress.

Lloyd Athearn, Executive Director of the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative, warned that focusing too much attention here could put outdoor access out of reach for a lot of people:

“If we start focusing on: ‘Close the gate there too many people out here,’ then that either causes people to go to other places that are ungated, which might cause a lot of the environmental impact, or it's all of these different cost and hassle barriers. If you're if you're thinking of some of these things, even if they're not high fees but you have to plan in advance and you have to schedule your reservation, I can tell you that's probably going to be more easily accomplished by a middle class or wealthier person with an office job.”

Quandary, a new Culebra

When I first started work on this project, Quandary struck me as an interesting case study because it seemed Summit County was trying to strike a balanced approach. Originally: they rolled out a parking reservation system with a free shuttle.

“What a neat little way to balance access against overcrowding,” I thought. Then they required paid reservations to use the shuttle, too.

So effectively, there’s no longer any way — aside from having someone drop you off — to hike Quandary during the popular summer summit season without planning and paying.

I’ve called attention to this in previous reporting on this, but I feel the need to repeat it here: several local governments help kick money over to CFI to fund trail restoration and upgrades. Summit County does not — through reservation fees, or otherwise.

In my view, what is happening to this mountain represents something we haven’t really seen since the Pikes Peak Cog Railway reached the summit: the development of alpine environments as full-blown tourist attractions.

Is this actually a viable strategy for conservation? How would this impact the outdoor experience? I’ve got answers.

The Absolute Mess that was the McCullough Gulch Parking Situation

Much like the situation over at Grays and Torreys; Quandary Peak’s popularity has long since outgrown its meager parking lot. Before the pilot program began, hikers parked any place their car could fit.

At the height of the 2021 season, cars filled the lot, lined McCullough Gulch Road, then started lining up along the nearby Blue Lakes Road. On some days, parked vehicles threatened to spill over onto the nearby state highway.

Summit County knew this was a problem. They’d been trying to hammer out a solution. But before they could properly flesh out a proposal, then-Assistant County Manager Bentley Henderson1 tells me safety concerns pushed them to act immediately.

“The intent was for the plan to be more fully complete and adopted before we took any action but that just wasn't an alternative, based on the urgency that was given us by the board,” Henderson explained.

One of the final straws: the parking overflow was so bad, an emergency vehicle couldn’t get through.

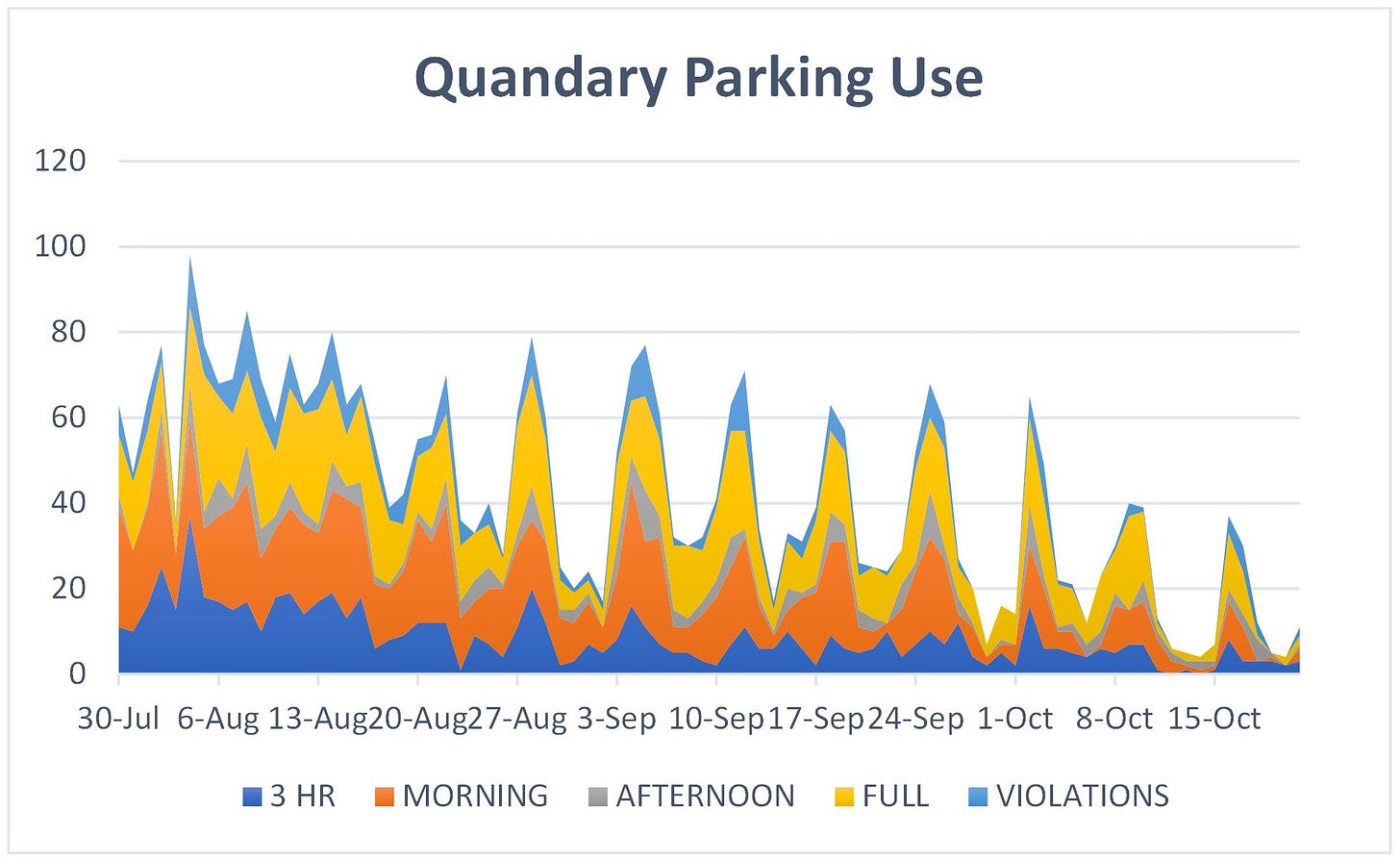

The county pulled the trigger on their parking shuttle program at the end of July, 2021. After a bit of advance warning to visitors, the first week of the shuttle looked like this:

Data for all graphs in this article is compiled from a variety of sources: shuttle use records from Summit Express, parking reservation records provided by the now former Assistant County Manager, and carpooling estimates from the Quandary Peak survey data.

From the word go: visitors were quick to adopt the then-free shuttle program; choosing it2 over the parking reservations by a wide margin.

I don’t have a daily tally from shuttle use. But according to Summit County Express owner Bob Roppel, the shuttle moved more than 12,000 people from the airport lot to the trailhead, throughout the 2021 season.

Based on the parking reservation data, we can place the estimated number of parked hikers at 8,938.3 Click the foot note if you're interested in seeing how I worked these numbers out. For those of you who detest math as much as I do, I turned all the data into this colorful graph:

The chart shows a pretty clear weekly cycle of visitors, peaking Saturdays and bottoming out midweek. But the valleys in the data points are much more shallow in August.

In normal-human-speak: that means trail use was actually pretty evenly spread out throughout the week during the summer. I’d chalk that up to the reservation system forcing hikers to spread out their trips.

You may remember: Steve Wilson of Alpine Rescue Team pointed out that with more restrictions on popular peaks, they’ve started getting more weekday rescue calls. Alpine Rescue doesn’t cover Quandary though, so I can’t extrapolate too much.

This chart just seems to show a similar trend on other mountains.

Having Reservations

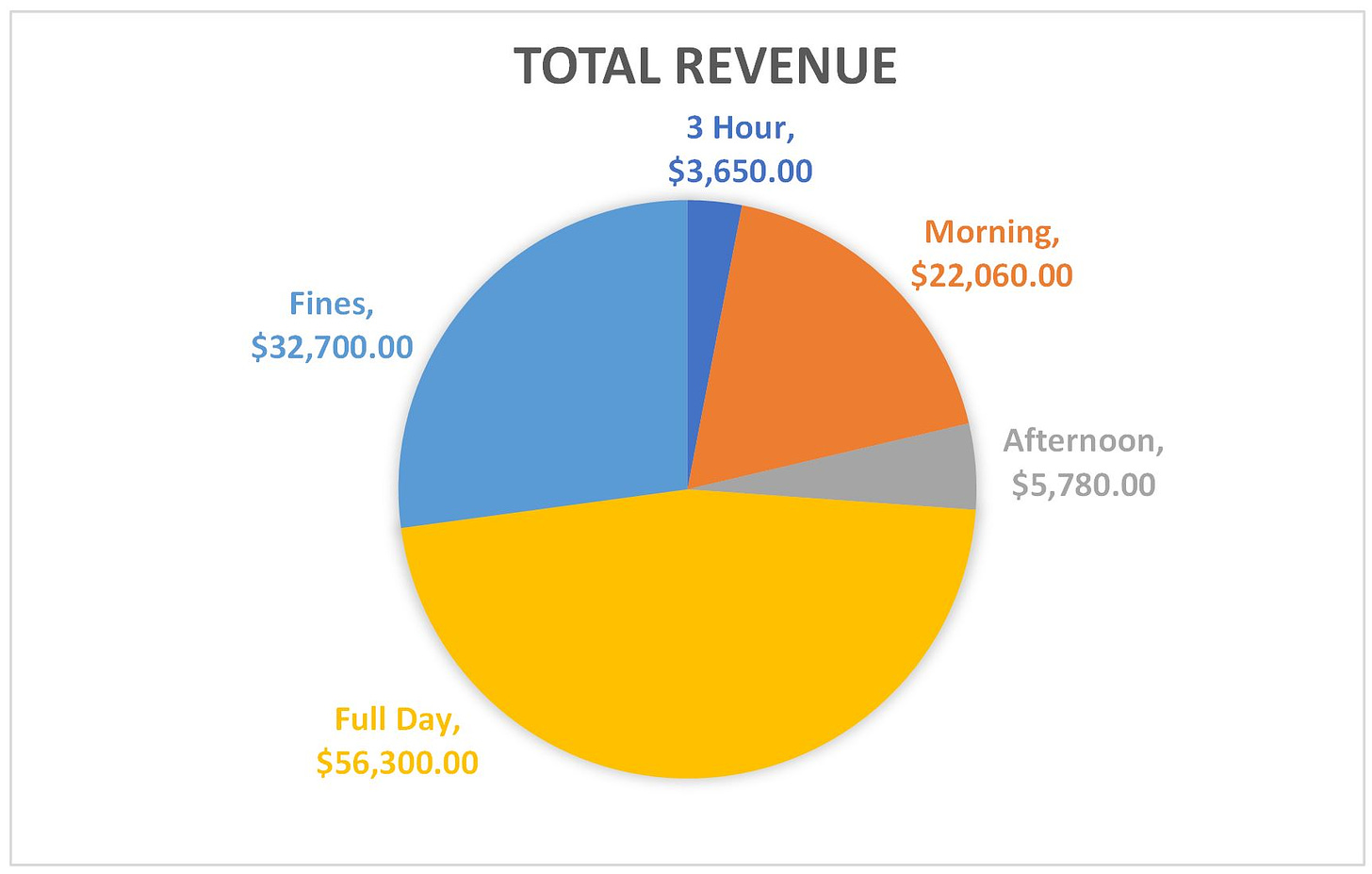

The overwhelming majority of parked hikers did make reservations, favoring either full day or morning-only time slots.

Summit County didn’t say how much money the permit system took in. But we can figure it out using the information we have.

The number of people who made each different kind of reservation

Exactly how much the different reservations cost

With a bit more math, we get a grand revenue total of $120,4904 from the pilot program, with more than a quarter coming from fines.

The system has been streamlined a bit since 2021. Now, there are no morning/afternoon options. This will no doubt corral more visitors into buying full-day passes, which made up the lion’s share of the system revenue:

What Next?

The shuttle program’s goal was to alleviate safety concerns by unclogging the road to the trailhead. Objectively, it achieved this goal, removing an estimated 57% of vehicles over the duration of the pilot program.

But that comes at the cost of convenience to some neighbors who may want fee-free access to local trailheads, as well as the tangible fiscal cost to run the shuttle.

As far as I’m aware, Summit County has not stated publicly how much it’s spending on this program. While the reservations contribute, we do know they’re not enough to pick up the full tab.

“It contributes to the shuttle system it doesn't fully pay for it.” Mr. Henderson said. “Our estimate is that the shuttle is going to be well into the six figures.”

I actually came to an estimate on how much this program costs to run, using algebra and a few other scraps of information I have. But it felt too speculative, and I felt the actual price tag is almost inconsequential for reasons I’ll get to in a minute.

This brings us to a bit of a crossroads in the Quandary Peak example. The peak management plan featured several other scenarios for expanding parking — even adding lanes alongside the road — but even their scenario that adds the greatest amount of parking spaces would already be strained by existing visitor numbers.5

Going down this road would likely bring us to the exact same discussion in another season or two.

I contemplated several other potential solutions here, but they amount to little more than navel-gazing. Summit County seems committed to the shuttle program, with possible expansion that could help lower the effective cost.

The Alpine Amusement Park

There are a lot of popular trails in Summit County, especially near Breckenridge; a fact local leadership is acutely aware of. As tourism increases, the shuttle could become the bones of a bigger infrastructure network that links a number of popular hiking spots to the downtown area.

“Other trailheads will be looked at so that the shuttle becomes more of a more comprehensive trail access program than just Quandary,” Mr. Henderson said.

The Gold Hill and Dredge trails were brought up as potential candidates.

This expansion could usher in a kind of alpine amusement park-style outdoor recreation on toughened-up, high-capacity trails, with Breckenridge at the core.

A study conducted by Doctors Loomis and Keske in 2008, examined exactly how much money visitors spend within 25 miles of the peak they plan to climb. In a previous article, I came up with what I consider to be a reasonable, inflation adjusted number of $113.29 per hiker. If the visitor is staying in a hotel or short-term rental, that number goes up to $358.61.

With the number of visitors we see on these peaks, Quandary is a multi-million dollar tourist attraction, all by itself.

Statewide, CFI estimates the economic impact of fourteener climbing to be in the neighborhood of $112.5 million.

Remember earlier when I said the shuttle program’s cost was inconsequential? Even my highest estimate is a full order of magnitude cheaper than the tourism that’s generated by Quandary Peak.

The money and interest are both present. Would it be possible to monetize the mountains, and use the revenue to help conserve them? How would this play out on other mountains? And how will this reshape the outdoor experience moving forward?

These are the questions I aim to answer in the final installment in this series. Subscribe now to ensure you don’t miss part 4, tomorrow morning.

Henderson resigned from his role before this report’s release

I don’t have enough information to determine whether hikers made this decision based on preference, or another confounding factor. Reservations could’ve been full, or they could’ve forgotten to make one, and returned to the parking lot instead.

From the data Summit County shared with me, I know they logged a combined total of 3,575 cars that either made reservations, or were ticketed.

Before launching the program, Summit County also did surveys to figure out how many hikers travel in cars together. They arrived at an average of 2.5 hikers per vehicle.

3,575 x 2.5 = 8,937.5

You can’t have a partial person on the trail, so we need to round up to the next whole number: 8,938. Ta-da!

The original pilot program let you make absurdly short half-day parking reservations. It’s possible some hikers made a reservation, came back too late, and also got a ticket.

This is not an exact figure provided by Summit County, rather, it was extrapolated by multiplying parking data with pricing information

Parking Scenario B from the Visitor Use Management Framework report created a hypothetical visitor capacity of 637.5 per day. Visitor use surpassed this threshold during the first week of the pilot program.