Tickets, Please — The Alpine Amusement Park Part 4

Could treating Colorado's most popular peaks like theme park rides actually save them from destruction and overuse?

This written investigation delves deeper into the issues highlighted in the documentary, "The Alpine Amusement Park." The previous installments in the series are below:

And here’s a quick refresher from parts 1, 2 & 3:

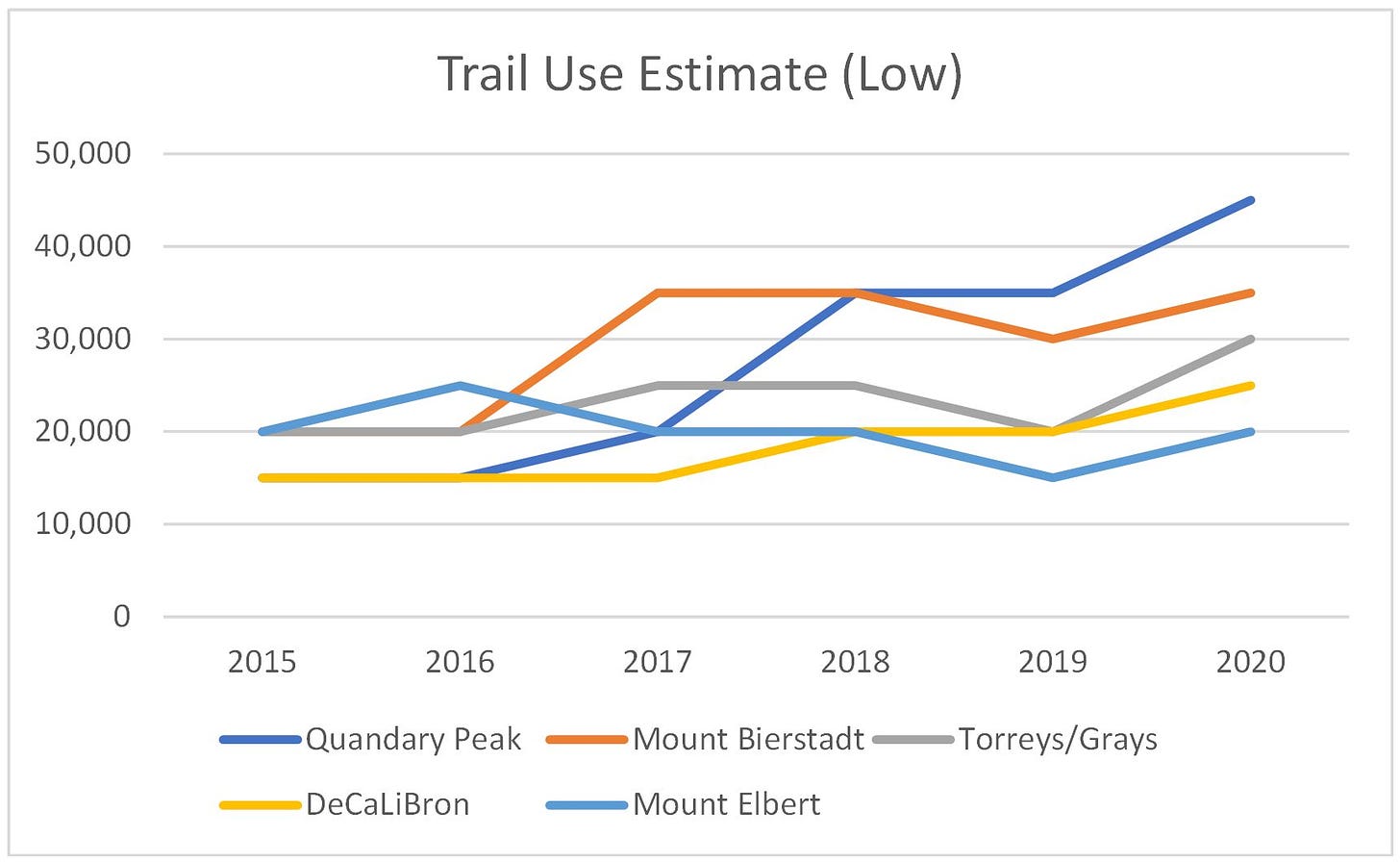

Trail use has been increasing steadily for a long time

Popular trails are being fortified against degradation

Small numbers of visitors violating “Leave no Trace” principles have a higher environmental impact than large numbers of visitors who do follow the principles

The “Crowd Rescuing” phenomenon helps hikers who are lost or suffering from minor injuries on crowded trails

The peak-bagging mindset may make visitors more likely to take unnecessary risks

Almost all fourteeners were unplanned, setting them up for logistical nightmares as popularity grew

The Quandary Peak shuttle successfully removed an Estimated 57% of hiker vehicles from the trailhead

Summit County has plans to grow a trailhead transit network

Fourteener climbing brings in huge amounts of tourism revenue

Summit County has struck a middle-ground in its quest to save Quandary Peak from overuse: paid parking reservations for those who want the convenience, and a free shuttle to ensure access isn’t hindered.

Meantime, the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative has worked diligently to ensure the trail is robust, hardened, and capable of carrying the tens of thousands of visitors to the top.

Both parties seem confident if there is a hard capacity limit to what Quandary can handle under these conditions, we haven’t found it yet.

The only expense to these solutions — aside from the spillover shuttle operation cost picked up by the Summit County taxpayer — seems to be a lost sense of remote wonder.

Alpine Rescue Team member Dawn Wilson puts it better than I could:

“That’s the unfortunate part of Colorado: it’s becoming kind of like an amusement park.”

In the previous installment, I suggested Breckenridge could be poised to become the nucleolus for a new sort of tourist attraction: a burgeoning alpine amusement park with the infrastructure to conveniently bring large numbers of visitors to a network of popular trails — no driving required.

It’s up to the residents of Summit County, and Breckenridge if they want to go down this path. But this begs a bigger question:

Is this solution even viable, or even desirable for the state’s other popular peaks?

Bierstadt

Let’s try to apply this solution to the next most popular peak on our list: Mount Bierstadt. The closest logical place to run the shuttle would be Georgetown, some 25 minutes away from the trailhead, and at the bottom of Guanella Pass.

The pass also effectively begins in the middle of a neighborhood street, meaning these homeowners would have to decide between having a bus station at their doorstep, or scores of cars passing through to reach the pass.

Bierstadt will likely face issues down the road, but there’s considerably more space at the trailhead for a solution to be implemented. It would probably make more sense fore stakeholders to focus their efforts up there, rather than down in Georgetown.

Grays and Torreys

By my estimate, this situation will be the most difficult to solve. The trailhead is at the end of Steven’s Gulch, a narrow, winding road lined with private homes. Expanding the upper lot is likely not feasible due to private property claims.

A shuttle system could, in theory, run from the lower lot to the upper. But finding a shuttle vehicle capable of reliably driving over the rocky terrain would likely be prohibitively expensive.

I predict Grays and Torreys will naturally fall out of peak popularity due to the Steven’s Gulch parking restrictions, though it’s still unclear where those hikers will be diverted.

DeCaLiBron

Any member of the mountaineering community likely knows these peaks are already caught in a precarious struggle for access.

The nearby town of Alma already charges for parking, so requiring paid reservations in advance instead isn’t much of a stretch. But due to the trail’s delicate situation: further infrastructure development here could pose problems.

If you didn’t know: the entire summit of Mount Bross, as well as several segments of the trail, cross private property. Due to the area’s old mining claims: wandering off route poses a higher-than-usual safety risk.

Liability concerns for the landowners have been inflamed by a recent ruling: James Nelson and Elizabeth Varney v United States of America. The short version is that Nelson went for a bike ride on an unofficial trail that crossed Airforce Academy property in Colorado Springs. Though it wasn’t on the map, it was commonly used, and the Academy knew the trail was there; they even erected signage for it.

Nelson hit a sink hole on the path and was badly hurt. After years of litigation, he was awarded several million dollars by the courts.

It’s possible infrastructure such as expanded parking, permitting systems, or shuttles, will pose a concern for landowners. Would these services give visitors a greater expectation of safety on the trail, and could these expectations lead to increased liability risk?

I see developments around this trailhead as something that could bog down talks between the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative, and the owners about preserving access.

Elbert

Of all the popular trails, I’m most inclined to argue this one can be left alone. Bringing back our trail use graphs once again: Mount Elbert has actually decreased in popularity since the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative deployed hiker counting devices.

Elbert is also the farthest of these top peaks from Denver, the greatest distance from I-70, and features the longest trail1, upwards of ten miles.

In short, Elbert lacks the pull-factors we’ve been discussing that led to Quandary’s snowball growth during the last five years.

Doomed From the Beginning

There is no panacea for degradation and crowding. What works on one peak will not necessarily translate to the others.

Colorado now has to reckon with an unfortunate truth: these trails were doomed to their current fate from the day they were beaten into the tundra. Use has expanded lightyears beyond anything the first hikers to summit could have possibly foreseen.

It’s left present-day policymakers with big problems, and not enough space to solve them. That’s why we need to be thinking long-term.

The true solution to trail crowding is a three-pronged approach that must occur at the macro level, or we will be merely pushing the problem from peak to peak.

The creation of new, well-planned open spaces

The fortification of existing spaces to handle increased use

The adoption of good trail etiquette to reduce impact

These solutions will require cooperation between state government, conservation organizations, and visitors themselves.

Future Proofing

This one is a job for Colorado state government. As the state grows, there will invariably be a need for more open spaces for recreation. These new spaces will need to be designed with room to grow. Here, laying out spaces with the model we’re seeing at Quandary may be a good starting off point. That may mean:

Parking lots away from private property and utility access

Robust roads that can easily accommodate emergency vehicles and shuttles

Designated parking lanes along the road itself

Access for public transportation

Reinforcement

The Colorado Fourteeners Initiative is already hard at work on this point: hardening up the infrastructure at popular trails, rather than trying to encourage hikers to move elsewhere. Lloyd Athearn, Executive Director of the CFI, argues that predicting human behavior is a fool’s errand.

“Shouldn't we try to meet the people where they are? And you know, if they want to climb fourteeners, let's improve the fourteener trail so that they can be more robust,” he argued.

And that’s effectively what the CFI is doing for the popular peaks. This means that provided we exercise good habits, these trails will not hit any kind of high-capacity limit.

This brings me to our next solution:

Reducing our Impact

While the CFI works to increase the amount of impact a trail can handle, hikers can also work to reduce the amount of impact they produce.

I made these points back in the beginning of this series:

Less about how many boots are on the trail, and more about how many leave it

Not how many people need help, but the severity of the situations they get into

Less about the raw number of visitors, and more about how they get there

Summit County’s visitor management plan acknowledges this too. Take a look at this excerpt from the report:

“The Quandary Peak trail has had improvements and appears to be successfully supporting the existing visitor capacity. However, this trail has seen conflicts between off leash dogs and wildlife. Human and dog waste, as well as illegal camping and campfires, additionally impact the water quality and infrastructure of Blue Lakes, an important water source for the Front Range. These issues have negative impacts on wildlife habitat, environmental quality, visitor experiences, and public safety.”

CFI has also branched out into this area by posting trail stewards near popular routes to encourage visitors to follow Leave No Trace principles.

These are all things every hiker can do to reduce impact on the trails, wildlife, and infrastructure that help keep our outdoor spaces accessible:

Avoid pulling off the road to park

Stick to the trail

Pack out all garbage and waste

Follow area camping and campfire rules

Leash pets to prevent wildlife conflict

Prepare, and pack smart to avoid over-burdening rescue groups

Be a good steward of the outdoors

This last point is probably the trickiest. I’ve discussed this with Eddie Taylor, of Full Circle Everest: trying to gatekeep the outdoor community often backfires. It’s by welcoming and mentoring newcomers that we increase reverence and care for these wild spaces.

That interview, by the way, is available here:

Fixing the problem would be so much easier if it just involved paving a massive parking lot, with sidewalks stretching from trailhead to peak. But aside from being unfeasible and largely unnecessary, it would take away what makes our experiences special.

The single most important change needs to be in the mindset of the outdoor community.

As Lloyd pointed out during our discussion: “Somewhere along the line climbing 14 years went from sort of in avocation of mountaineers and climbers to a very mainstream bucket list type thing.”

To save our open spaces: we must return to experiential, rather than list climbing.

As I’ve laid out throughout this series: those focused only on summiting are apt to press on past their ability level, impending exhaustion, and into risky conditions.

Meanwhile: the profile of the hikers is shifting from experienced mountaineers, toward younger, less experienced visitors with a taste for adventure and inclination toward spontaneity.

Make no mistake: newer hikers aren’t at fault for trail crowding and degradation. Conservation principles and preparedness are not innate, but ideas taught and learned through a healthy community.

The best thing we can do is pass on our love and reverence for the outdoors, and the idea that every step is special — not just the final one we plant on the summit.

Thank You for Reading

This journey has been a long one. The interviews included were conducted over many months on whatever time I could spare away from my day job. If it’s something you enjoyed, found informative, or want to see more: click the subscribe button below.

It’s free and helps support investigations like this one.

I’m aware other fourteener routes are longer. For the purposes of this discussion, I’m only referring to our list of 5 most popular trails.

I love Colorado. One day I'll get back. Your information is great and helpful!!