Yosemite Dumped its Reservation System. Is the Tide Changing for Outdoor Access?

New data shows overcrowding impacts a tiny percentage of park space — but broad restrictions cut access to all of it. The big takeaways for National Parks, and their visitors:

Accessing the outdoors is getting more difficult and crowded. More people have gotten interested in exploring, but there’s a limited number of places to do it.

As Rep. Katie Porter of California phrased it during a recent hearing on overcrowding: “You can get more pie, or you can divvy up the pie.”

Most local governments and park officials have opted for the second approach, requiring reservations, timed entry, or payments to visit certain areas and trails. I did a whole documentary on this happening in Colorado.

That’s why Yosemite National Park bucking the trend — completely ditching its reservation system for 2023 — absolutely floored me.

“We’re not Trying to Get to where we were; We’re Trying to Get Ahead.”

Scott Gediman is the Public Affairs officer for Yosemite. He describes crowding and visitor management as a problem that’s been going on for almost half a century; one that until now, has only been addressed by knee-jerk quick-fixes.

The way forward, Gediman tells me, means first getting a better pulse on the problem. Right now: Yosemite doesn’t have a good baseline on how many visitors can be expected in a normal year. 2022 saw road work. 2021 and 2020 both bore COVID restrictions. 2019 is the most recent unrestricted year on record. And a lot of habits and hobbies have changed since then.

“The idea was: during this planning effort, let’s just do no reservations. People will come in and then we’ll — A, see how all the improvements work; and B, it will give us the baseline. We have not had unrestricted visitation since 2019.” — Scott Gediman, Yosemite National Park

There’s a similar issue in Colorado recreation, going far beyond the state's handful of National Parks. Outdoor recreation has become a confusing web of rules, reservations, and permits — particularly when it comes to the state’s famous 14’ers.1

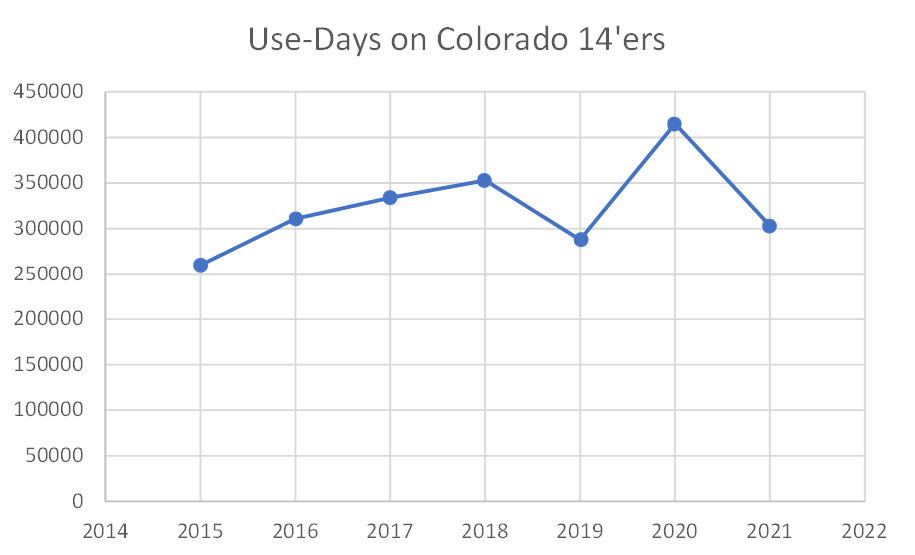

This graphic combines every yearly trail use report from the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative, or CFI, dating back to 2015:2 (that’s the first full year of data after TRAFx infrared counters were deployed)

2022 data isn’t available yet

2021 saw a post-COVID crash as restrictions took affect

2020 brought a COVID boom with few trail restrictions and little else to do

2019’s wicked wildfire smoke drove many people indoors.

2018 had a shorter viable summer season because of lingering snowpack

That leaves us with just 3 years of dependable numbers, and more “abnormal” years on record than standard seasons. How can we make any kind of sweeping decisions, impacting hundreds of thousands of people, based on that?

After an almost 3 year march deeper into restricted outdoor access, I’m happy to see at least some policymakers are recognizing: bad information makes bad policy.

To course correct, the House Committee on Natural Resources held a hearing to address the issue. Here’s perhaps the most shocking thing to come out of their investigation:

“98% of Visitors Never Get more than a Half Mile of Their Car, Using just 1% of the Park.” — Hannah Downey, PERC

“Parks hosted a total of 297 million recreation visitors. more than half of those visits however, were to the 25 most visited parks in the country, representing just 6% of the park system,” said Hannah Downey, with the Property and Environment Research Center (or PERC.)

Downey was one of several panelists to testify during the overcrowding hearing. She also came to the table with one of the most damning arguments I’ve ever heard against timed entry and reservation systems:

“Those visitors do not disperse evenly. Yellowstone National Park for example, estimates that 98% of visitors never get more than a half mile of their car, using just 1% of the park,” Said Downey. “While it is encouraging to see widespread enthusiasm for our parks, congestion in popular areas is negatively impacting visitors, park service personnel, and the natural resources our parks were created to protect.”

Let me cut right to the core of this: overcrowding is happening in a fraction of a fraction of locations in our open spaces. Park officials and policy makers very well may be restricting access to 100% of a park, to prevent crowding that’s taking place on just 1% of the land within.

Or as Doctor Will Rice — head of the Wildland and Recreation Management Research Lab at the University of Montana — puts it: “Crowding can not necessarily be assumed based on the number of people entering the park. Perceived crowding must be empirically identified based on gathering data on the visitor experience.”

The Big Problems

The hearing lasted less than an hour and a half. But the panelists did a pretty good job pointing to concrete problems with actual, tangible solutions. I’ll walk you through them:

Addressing staff and resource trouble

Getting better information about visitor habits

Turning modern technology into an asset; not a liability

Real quick, in the interest of transparency — if you’d like to watch the hearing for yourself, here is the full 1 hour, 26 minutes, and 35 seconds of its naked glory:

I’m also attaching a list of all the speakers down in the footnotes, where you will be able to find out more about their work and backgrounds.3 I was not able to include a quote from everyone who attended in this article, but I still wanted to take the time to give you a full picture of who was there to shape the conversation.

Conquering the Cascade Failure of Resource Loss

It’s not just that open spaces are getting busier. Some are struggling with fewer staff to manage the bigger crowds.

“On the Zion website, it shows that from 2010 — so the last 10, 11 years — visitation has gone up by 90%, from about 2.6 million, to 5 million. In that same period, the number of full-time equivalent employees has gone down. It was around 184, now it’s down around 177,” said Rep. Katie Porter, (D) CA-45, and subcommittee chair.

National parks seem to be facing the same problem a lot of ski towns are coping with: employees can’t afford to live nearby — at least not compared to what they’re paid. For their part, some ski resorts are now building on-site dormitories for workers.

Congress is considering a similar idea.

Ranking committee member, Rep. Blake Moore, (R) UT-1, brought up his pending bill, the LODGE Act (H.R.7165.) If passed, the government would be able to develop housing on or near public land, and rent to employees.

Downey also brought up the importance of re-upping the creatively named Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act, or FLREA.

Despite my sarcasm, this is actually a fascinating bit of legislation — and no, I didn’t just have a stroke writing that sentence. These are the two nuggets that matter the most:

A kind of “You earn it, you spend it,” provision requires 80% of all recreation fees be spent where they’re generated. That means ticket prices in Yosemite fund upgrades at Yosemite. The NPS can’t shuffle that money to some project in Nowhere National Park, out in BFE.

Extremely strict rules on who has the authority to slap fees on national land. It also spells out what you can, and can’t be charged for.

Since learning about that second part of the law, I’ve started to wonder whether some trail reservation systems that have been springing up are actually illegal. If you’d like to see me dig deeper into this, please let me know. Investigations like that take a ton of time and resources, and I’m trying to direct my time and effort toward the kinds of stories you’re all actually interested in.

The rest of the FLREA mostly does its job in making sure more visitors translates to more funding for improvements and maintenance. But keeping up with demand is a whole other ordeal.

“The differed maintenance backlog now totals more than 22 billion dollars, and includes everything from eroded trails, crumbling roads, failing wastewater systems, and dilapidated visitor facilities,” Downey said. “Significant funding was provided through the Great American Outdoors Act, but the reality is that the underlying issue remains unresolved, which is a lack of attention to routine maintenance.”

The staffing situation certainly isn’t helping that backlog. Provided the LODGE act becomes a reality, it seems the NPS will eventually get the tools it needs to resolve these problems.

Figuring out the Unknown Unknowns

Even if the LODGE act passes, it will take years for us to actually feel the impact. By then, National Parks will be facing a new problem, and the NPS will be playing catch-up once again.

Part of the reason so many parks are in a poor position to plan ahead is because — well — they don’t actually have a plan.

“Parks have been required, by law, since 1978, to figure out how many visitors their park can handle, and to make a plan to manage visitation,” Porter explained. “In preparing for this hearing, I learned that very few parks have made these plans.”

Some speakers blamed this problem, in part, on the Paperwork Reduction Act. If a government agency like the NPS wants to survey or interview visitors, they need to run it by the Office of Management and Budget first.

You might have a hard time believing this, but the bureaucracy doesn’t move very quickly. (Gasp!) By the time a survey is approved, the questions a park wanted to ask its visitors may be irrelevant. So why bother, right?

This is an unimaginative cop-out.

Aside from the fact this problem actually pre-dates the law; there are plenty of other ways to gather information on park use and crowding without running a survey. It also shows a lack of collaboration between the parks, and the surrounding communities they are a part of — which I’ll get to in a minute.

Most Parks are AWFUL at Taking Advantage of New Technology

These parks argue it’s hard to get information about the public. Visitors, in turn, seem to be having a hard time getting information about the parks.

Simply put, many state-run reservation systems just suck.

Last year for example, my investigation into Colorado’s IPAWS system found a massive flaw in the site may have deprived more than 50,000 people the opportunity to camp.

During the hearing, Doctor Rice explained how reservation systems put certain experiences completely out of reach for would-be visitors.

“According to a 2021 newsletter from recreation.gov, in a popular campground, a would-be camper may have a 0.3% chance of successfully booking a campsite through a reservation-based rationing mechanism This chance is likely lower for those with jobs that prevent them from being able to plan trips months in advance; those living in rural areas with limited highspeed internet access; and those who simply have jobs that prevent them from being able to be online to make reservations whenever permits are released for reservation.”

Frank Dean, President and CEO of Yosemite Conservancy, pointed to several huge shortcomings of the reservation system. With spotty cell service at park entry points, many visitors couldn’t actually show proof of their reservation.

Spanish speaking visitors in particular seemed to have a tough time understanding the system — probably because the booking site is only available in English.

Timed entry and reservation systems put a hard cap on how many people could visit. But there’s also an additional, impossible-to-measure group of people that were kept away by the poor design of the system itself.

The Digital Draw: How Social Media Creates Chaos for National Parks

Even when it’s working correctly, technology works against the NPS. Panelist Hannah Downey lays a good deal of blame at the feet of influencers for this issue:

“Horseshoe Bend for example is a really popular national parks service area, and that went from about 4,000 visitors a year, to then with a rise of Instagram and all of these iconic photos emerging and circulating on people’s feeds, over 2 million visitors a year. That’s huge.” —Hannah Downey, PERC

We can’t put an exact number on how many people hike because of an pretty picture on their feed. But if the plural of anecdote is evidence, then boy howdy do we have a lot of evidence this is taking place.

Search and rescue volunteers have explained to me that the locations they get called to most can actually be cyclical, as popular trails trend on social media and in the news.

They also explain that when a hiker is motivated by the prospect of a good photo op, they’re more likely to put themselves in danger to reach the end of the trail. I’ve written more about these rescue trends here if you’re interested.

Fellow writer Kelton Wright also does a great job exploring the ties between social media, and floods of new visitors in her piece, “Who gets to know?” Worth checking out after you finish up here.

I think the root cause of all this is simple association. For the same reason name recognition can make or break a political candidate on election day; a tourist looking to get outside will probably seek out the places and views they have already heard about.

Downey suggests that this can be fixed with some clever use of the same technology that first attracted those visitors. A social media trend has been going around for a while, where travel bloggers and photographers show “Instagram VS Reality,” comparing their perfect pictures with the actual crowds at these locations.

Here’s my example from the top of Quandary Peak:

Downey recommended using a few well-placed webcams to give visitors more realistic expectations, and directing them toward other areas of the park instead.

“We are so blessed with this incredible park — and certainly we need to be careful in how we distribute users so that we don’t have people just climbing into geysers or falling off cliffs — but at the same point in time, again providing some of that information is going to be really essential to visitors.”

Representative Moore was quick to point out a pending bill to digitize trail maps and make it easier for visitors to see lesser-known destinations parks have to offer.

“If only we could get those accessible through more technological advances like applications on our iPhones — oh wait, we passed MAPland out of the Natural Resources Committee this year unanimously and actually did something productive.”

“Freedom is Central to Outdoor Recreation and in many ways, National Parks are Emblematic of the Larger Freedoms we Enjoy as Americans.”

—Dr. Will Rice

Even if you subscribe to the idea that more visitors = more bad — I don’t, and have thoroughly debunked this argument in The Alpine Amusement Park — there is another side of that coin to consider.

The Yosemite Conservancy acknowledge that the park reservation system resulted in fewer visitors, and in turn, had a negative impact on businesses in the community. Before anyone runs in here crying environmental absolutism (i.e. “screw your businesses, we need to protect the trees,") remember our earlier problem: the staffing struggle.

As we discussed, housing costs make it cost-prohibitive for many people to take jobs at national parks. But if you run the surrounding communities into the ground, you’ll have the opposite problem; good luck getting employees to come live and work in a ghost town.

Gateway communities also have a strong incentive to preserve and safeguard the natural resources that attract tourists in the first place; it’s all about balance.

“We know that visitors don’t just come to national parks, they are welcomed in our gateway communities. They attend businesses and support an economy in our region. We have non-profit partners that assist us in planning, and provide some funds that help us in those ways,” said Jeff Bradybaugh, Superintendent of Zion National Park.

Bringing the conversation back to Yosemite: part of the reason the park opted for a full rollback of the reservation system, is to give businesses a chance to pitch alternative solutions that wouldn’t choke out their livelihood.

“We want visitors, local businesses, tourism officials, elected officials, we want to hear from everybody,” Gediman said.

And with the hearings going on, Gediman is also acutely aware that other parks are watching what unfolds at Yosemite, and taking notes.

“A lot of things in Yosemite aren’t ‘paving the way,’ but they are applied to other parks.” …. “We’re not doing this to tell other parks what to do. But we are all working collaboratively and hoping some of the lessons we’ve learned here are going to help other parks.”

Forget the “New Normal” — We Don’t Know What Normal is Anymore

I appreciate Yosemite’s desire to approach the problem with open minds and a clean slate. Likewise, it’s promising the House Committee on Natural Resources is also taking a step back to get ahead of the problem for a change.

In rare form, it also looks like we have actionable steps that national parks can take to help manage crowding:

Push forward with representative Moore’s LODGE act: improved staffing means parks will have an easier time keeping up with routine maintenance.

Come up with creative ways to gauge visitor preferences: just because you can’t run surveys, doesn’t mean you can’t figure out which trails are popular. For example, the NPS already uses infrared counters to measure foot traffic in certain locations.

Fix bad technology: Government agencies have a terrible track record with building websites. I’ve previously reported about the problems with Colorado’s reservation platform, IPAWS. The system was designed to sell hunting licenses, not control access to all outdoor spaces. Parks that plan to stick with reservation systems should be sure they actually work before going any farther down that road.

Play smart: Downey brought up several great points about pulling back the veil on those picture-perfect versions of our National Parks. Providing a way for visitors to see the crowding in real time, could help parks better utilize the other 99% of their land and facilities.

I can’t overstate how insane it is that some National Parks are actually restricting access to 100% of their space, because of crowding taking place on 1% of the area. Taking a step back to consider these fixes will allow Yosemite — and many other beloved destinations — to improve conservation without depriving Americans the chance to enjoy these natural wonders.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider sharing it with your friends; it’s a fantastic way to help other adventurers and outdoor enthusiasts find my work.

And if you’re not signed up already, subscribing to Cole’s Climb is a great way to support independent writing — and make sure you’re the first to get original reporting, and mountaineering resources to prepare for your travels.

Peaks taller than 14,000 feet

CFI didn’t have full coverage with its infrared sensors until 2015, although the organization has existed since 1994, and Colorado mountaineering has been around for quite a while longer than that.

Alphabetized list of speakers from the hearing:

Jeff Bradybaugh, Superintendent, Zion National Park

Frank Dean, President and CEO of Yosemite Conservancy

Hannah Downey, Property and Environment Research Center (PERC)

Rep. Blake Moore (R) UT-1, Ranking Committee Member

Rep. Joe Neguse (D) CO-2

Rep. Katie Porter (D) CA-47, Committee Chair

Doctor Will Rice, head of the Wildland and Recreation Management Research Lab at the University of Montana

Rep. Matt Rosendale (R) MT-2

Excellent write up and quite revealing. I'm pretty familiar with much of this as a full-time camper but it's not talked about much outside of camping circles.

One thing I'd like to see is for parks to bring back "First Come First Serve" slots. Back in the day these were pretty common but it's rare now. Quite a few full-timers are the kind that go with the wind in their wanderings so reservations put a crimp in it (as well as make it more difficult to find unreserved spots in reservation only parks).

In Florida it's a big problem because of snowbirds booking up all available sites many months in advance so locals are often out of luck when they get the urge to take their family camping for the weekend.

Ray

P.S. Welcome to Florida! I was born and raised here and it's still a basecamp of sorts for my wanderings : )

Thanks for the link, Cole 💛