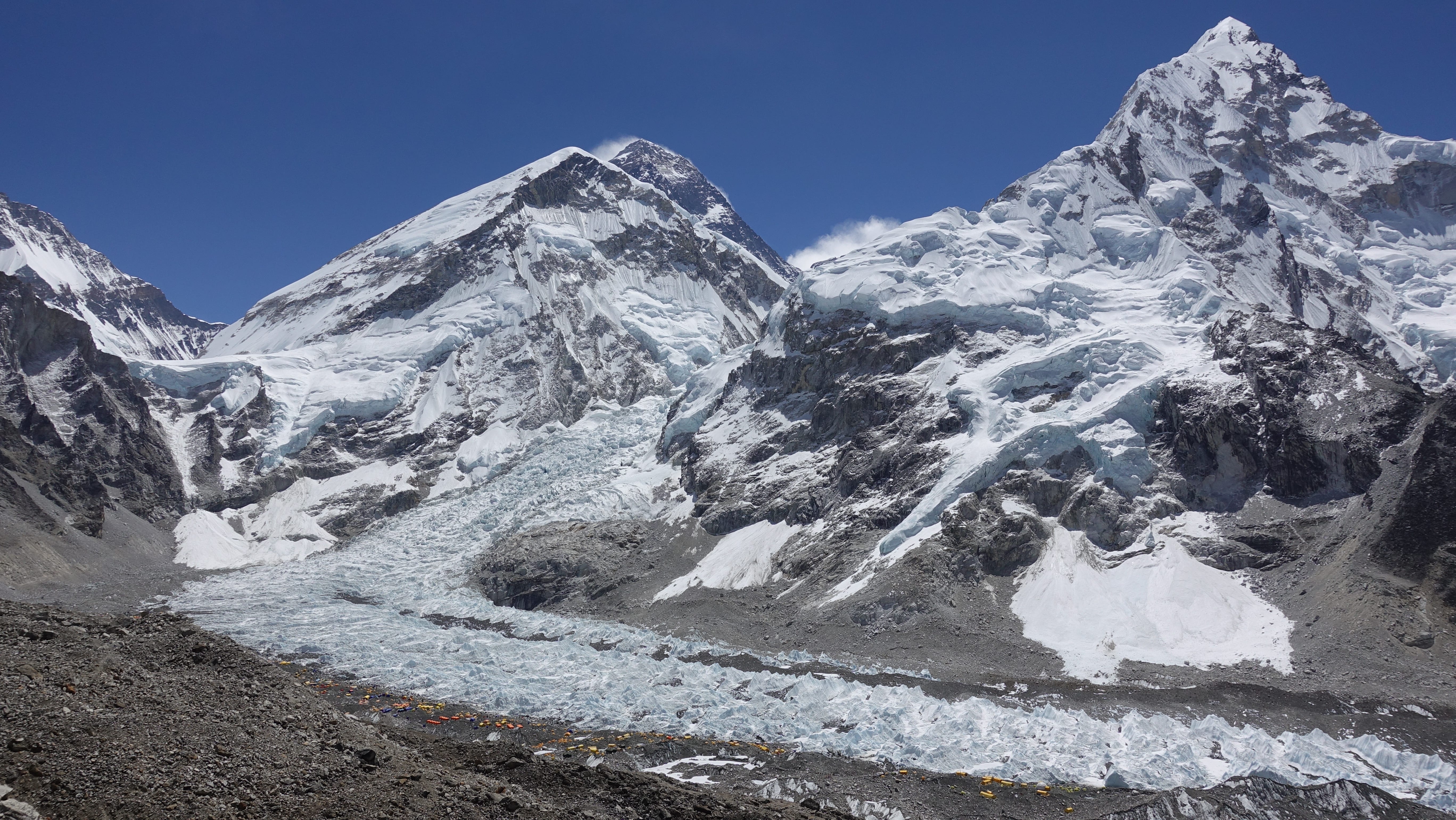

The 2015 Gorka Earthquake killed 8,790 people — including 19 on Mt. Everest — and left more than 22,000 others injured. The quake hit just before noon, Nepal Standard Time; shortly after Jim Davidson reached Camp One on the world’s highest peak.

The resulting avalanches pulverized basecamp. The necessary ropes and ladders between basecamp and C1 were swallowed by crevasses or pulverized by gargantuan chunks of ice and debris in the Khumbu Icefall.

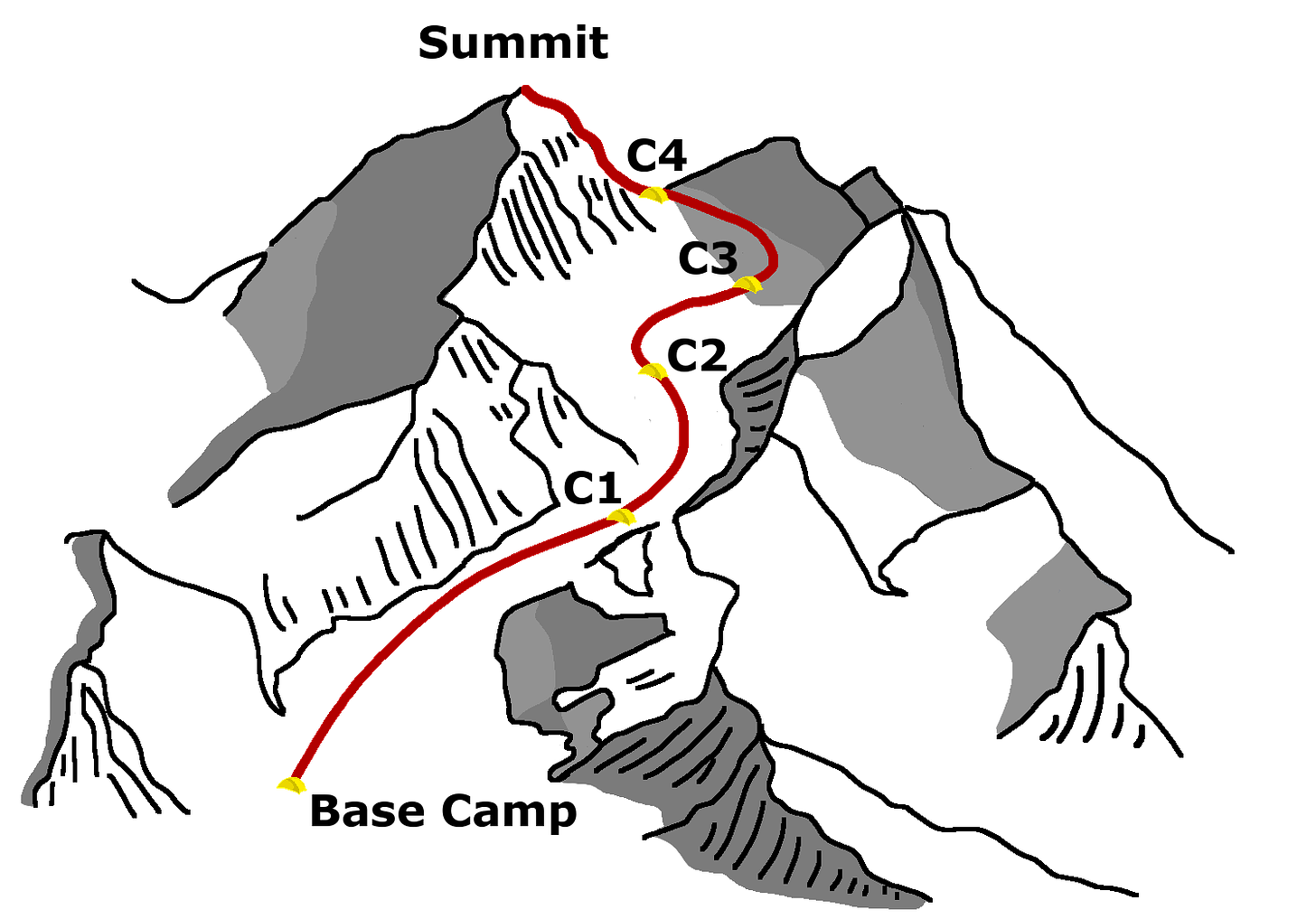

Climbers in C1 and C2 were uninjured but trapped. The expedition lacked necessary equipment to rebuild the route through the Icefall. After a long wait: they opted to try a risky high altitude helicopter evacuation.

After a successful emergency airlift, Jim and his fellow climbers began the long journey home, working to help the Nepali people suffering the impacts of the earthquake along the way.

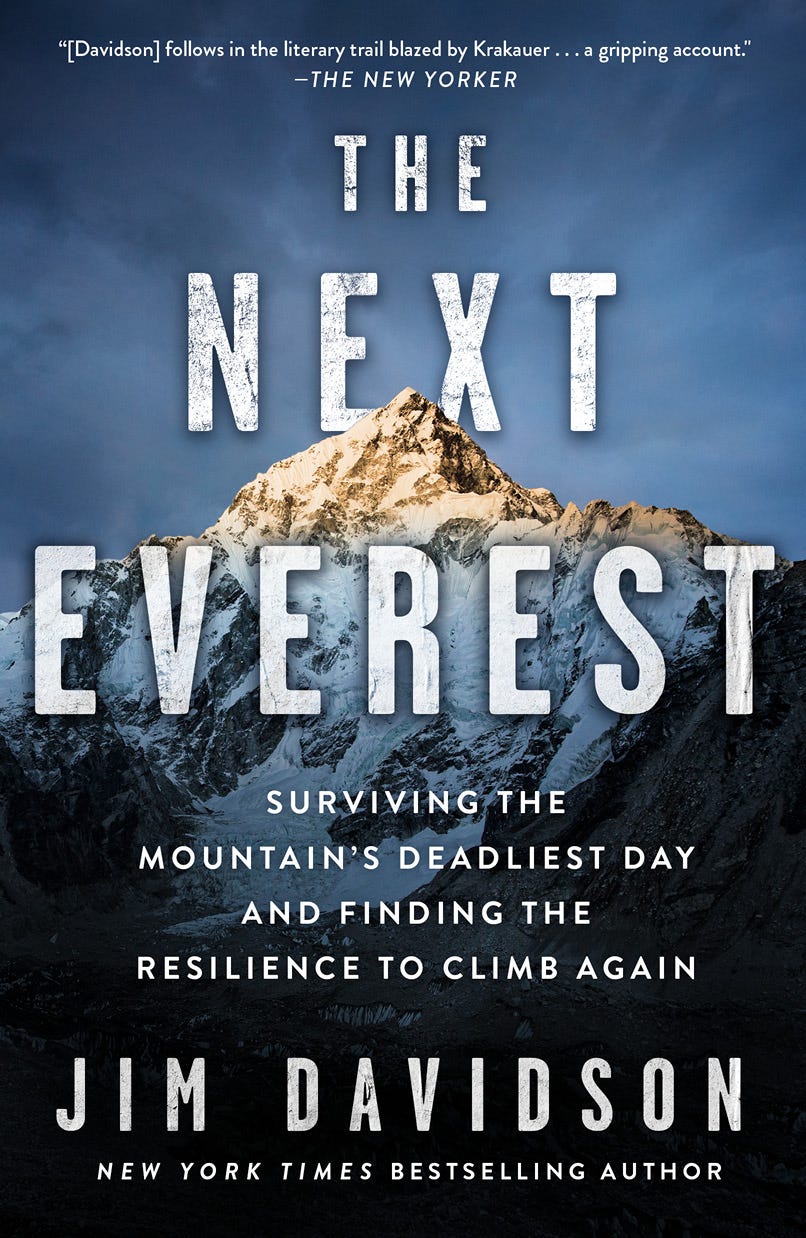

Jim Davidson documents this survival story, journey home, and eventual return in his book: The Next Everest.

Interview Notes

1:00 — The proper process for Everest

5:00 — Shoring up against threats to your expedition

7:15 — What it means to be an “eyes open traveler”

10:40 — The Everest packing list

12:00 — High altitude = less brain power

16:00 — The day of the Gorka Quake

22:30 — Frantic moments in an emergency

26:00 — How to survive for the sake of your family

28:30 — The agony of waiting during a crisis

32:00 — Choosing what matters, and what to leave behind

34:30 — Turning from “never again,” to “going back.”

38:00 — Post traumatic growth: prepping better the second time

40:45 — A close call near the summit

44:00 — How the expedition withers your body

50:00 — The key takeaways from the book

53:00 — What to do after accomplishing your biggest goal

“You Need to Make Dozens of Mistakes on Dozens of Climbs, so You Don’t Make that Mistake up High.”

Preparing for Everest takes years — even decades before you begin physically training for the goal. One of the most important stages of prep work involves making errors on other adventures, when the stakes are lower. This lets you refine your packing process, learn your weaknesses, and figure out how you can better prepare in the future.

I’m sure you can relate to this process of trial and error, even if it wasn’t on the mountain: what’s something you got wrong, that helped you better prepare for a future situation?

Of course — a simple mistake on Everest can bring potentially life-threatening consequences. As Jim points out in our discussion: something as simple as forgetting sunscreen can be extremely dangerous.

“Nothing New on Race Day”

Speaking of packing: in an environment when tiny details could be the difference between life and death, you need to be extremely well acquainted with your gear.

How do your socks fit in your boots when your feet swell?

Do your gloves feel awkward when adjusting your straps and jacket?

Are your pants getting caught on your climbing harness?

These are questions you must be able to answer before your expedition.

“It’s okay to learn the hard way on smaller races, and smaller climbs. but when you get to the Olympics final, or when you get to Everest, you don’t want to make those mistakes. So, make them elsewhere and bring that knowledge and good gear with you.”

“The Higher You go; the Dumber You get.”

There also needs to be a great degree of familiarity with how your equipment functions. These things should be muscle-memory by the time you reach Everest. When you are in a low oxygen environment, your cognitive capabilities take a big hit.

Things that seem simple at sea level become difficult to grasp when you’re in the Death Zone.1 In those moments, being comfortable clipping into a safety line or correctly adjusting your equipment could save your life.

The Day of the Quake

After two consecutive avalanches hit, lifting their tent off the ground, Jim and his tentmate realized they were in an earthquake. The Next Everest describes a constant trade-off on the mountains between safety and speed: lingering too long in a questionable spot can be dangerous. But so can proceeding without proper protective gear.

In the initial shaking, Jim was concerned the tent could be swept off the mountain. He thought his best chance of staying on top of the avalanche would be outside. So, Jim ran out of the tent with an avalanche beacon — but no shoes.

“I ran out into the snow in my socks! Now, that doesn’t sound like somebody who has been climbing for 34 years. But that’s because I thought about how long it was going to take me and said, ‘heck with this.’ I’m not sure going outside without boots on was a very good long-term decision. But at the moment, I couldn’t justify the time.”

The hours and days that followed would involve a lot of waiting: for an escape plan, for the rescue chopper, for the airport backlog to be cleared, and for a flight home. The journey would also involve moving from a place of relative, temporary safety, through areas the earthquake hit with increasing intensity.

At each step of the journey, Jim and his fellow climbers tried to fill this time by pitching in to help the local community.

“By helping others, you’re helping others yourself as well. That kind of hardship forges heartiness.”

“The Turning from that ‘Never Wanting to go There’ to Actually Wanting to go back — it was a Slow, Handwringing, Almost Reluctant Process.”

Jim explained he felt awful being safe at home while Nepal struggled. He spent time speaking, raising money, and encouraging others to visit the country to help the economy once the recovery was underway.

This process of raising awareness gradually changed Jim’s mind. He still dreamed of summiting Everest, and after encouraging others to visit Nepal, Jim decided to lead by example.

“It was a big pill to swallow. But I also knew that by taking on big challenges — that’s what allows me to refine myself into a better version of me. I think that’s the advantage of taking on any big challenge.”

Living through the 2015 disaster also changed the way Jim prepared for his return trip. For example: after borrowing a satellite phone2 to contact his family members while marooned at Camp One, Jim upgraded his communication setup.

But there was also a lot of fear to overcome. In his book: Jim describes the unease that followed the quake. He went so far as to try and sleep while wearing his boots, beacon, and helmet in the event another avalanche struck at night. In our discussion, Jim described moving past these worries as “post traumatic growth.”

“You’re Leaving a Piece of Yourself — Mentally and Physically — on the Mountain.”

During his second trip, Jim was on the mountain much longer, and explains the challenges of life in camp. Because of the lack of high-protein food, climbers burn through pounds of muscle3, wasting away for the weeks they spend on the mountain.

Jim also endured solemn, and scary moments on his final push to the summit: passing the remains of two deceased climbers, while having a gear malfunction that caused him to lose feeling in his foot.

“You see them passed away and you have to start asking yourself some very hard questions. Did something minor happen to their equipment? Should they have taken the hint?”

While ultimately able to fix his technical problem: Jim also writes about the additional considerations that come with being a climber with a family back home. It’s something that also came up in our discussion as well:

“Your friends and family — they don’t really care if you summited the mountain or not. They want you to achieve your dream and they’re happy if you reach that. But frankly they just want you to come again, safe and sound.

Ultimately, I had to as the question I’m sure you’re wondering about Everest: how was the view?

“It was like being an astronaut looking down on the earth; it was a magical moment for sure.”

“After Enlightenment, Then Chop Wood.”

After standing at the highest point in the world, you have to come down. Jim tells me that he was up there for about 15 minutes out of the entire 6-week expedition. As a high-altitude climber, where do you go from here?

Jim describes this challenge with the Buddhist saying: After enlightenment, chop wood, carry water. Your goal is not your final destination. Afterward, you go back to your normal life, routine, and chores. But you return an improved person, with a different understanding to apply to that routine.

Then, you set your sights on something new.

“I think that’s the real beauty, is to pick a big challenge. A challenge that makes you nervous, that scares you. Because you’re going to have to do more, and you’re going to have to become more. And that’s where the magic lies.”

And of course — as we’ve discussed many times before here on Cole’s Climb — the goal itself isn’t what changes you. As Jim beautifully puts it: change comes in the process of becoming the person who can achieve that goal.

One more time: if you’d like to check out Jim’s book, you can get “The Next Everest,” here. It’s well-worth your time.

Original music for the Trail Talk podcast is composed and produced by Ty Ellenbogen.

If you like what you listened to, please do consider subscribing. I’d love to have you in the responsible outdoor community. I promise to never spam your inbox, and only share the best interviews, stories, and reporting on the outdoor community.

If you’re already subscribed, leave a like! It’s a great way to let me know the episode resonated with you.

Elevation above 8,000 meters, or 26,000 feet above sea level. Here, the oxygen content of the air is so low, your body cannot survive. On Everest, climbers use supplemental oxygen tanks called Os to push above C3

Normal cell phones don’t work well in such remote places. In previous stories, I mention using a Garmin InReach to send emergency messages. There are different kinds of devices, but not all of them have the ability to make calls

Upon returning, Jim says he lost 22 pounds while changing his body fat percentage from 13 pre-expedition to 18. On Everest, it’s not possible to pack in all the necessary kinds of food which leads to muscle loss

Podcast #16: Surviving the Deadliest Day on Everest with Jim Davidson